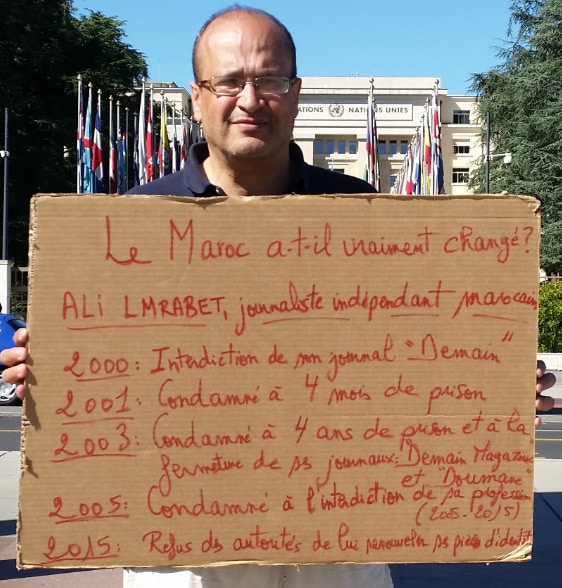

Outside the United Nations building in Geneva, Switzerland, Ali Lmrabet is in his 28th day of hunger strike. The journalist and satirist is protesting what he sees as the latest bid from his country Morocco to stop him from doing his job.

This statement was originally published on indexoncensorship.org on 22 July 2015.

Outside the United Nations building in Geneva, Switzerland, Ali Lmrabet is in his 28th day of hunger strike. The journalist and satirist is protesting what he sees as the latest bid from his country Morocco to stop him from doing his job.

In a period spanning over a decade, Lmrabet, who was the editor of two satirical publications, has continuously been targeted by Moroccan authorities. In 2003, he was jailed for reporting on personal and financial affairs of Morocco’s King Mohammed VI. His magazine Demain was banned. Though initially handed down a three-year sentence, Lmrabet was released after six months. But his troubles were far from from over: in 2005, he was banned from practising journalism in his home country for ten years, over comments made about the dispute in Western Sahara between Morocco and the Algerian-backed Polisario Front.

Now authorities are seemingly using bureaucracy as a tool to try and silence Lmrabet again. As his ban expired in April this year, he returned to Morocco with the aim of relaunching Demain. But there he was denied a residency permit, without which he is unable to set up the magazine. In a further complication, he also needs the residence permit to renew his passport. When this expired on 24 June, Lmrabet, who was in Geneva to participate in a session of the UN Human Rights Council, decided to start a hunger strike.

“He is very tired,” his partner Laura Feliu told Index on Censorship in a phone interview. She explained how the heat in Geneva has played a part in leaving Lmrabet drained of energy, and while he hasn’t had any serious health problems, he is experiencing sensations of seasickness.

Lmrabet’s protest takes place outside the UN offices, though a heatwave forced him to move inside on Sunday. He sleeps in a Protestant church near the centre of the city. Subsisting on water and some sugar and salt, he has lost at least seven kilograms since the start of the strike.

“He started a hunger strike to protest because he has been denied the right to work as a journalist,” Feliu explained. But in addition to having his free expression and press freedom curtailed, he also has another problem, she adds: “He is denied his right to an identity.”

Lmrabet has support in his country. Some 100 well-known Moroccans from the worlds of media, human rights and academia have signed a petition to the government calling on him to be allowed to renew his documents and continue his work in journalism. Independent and prominent human rights organisations in Morocco are also backing him, according to Feliu.

The response from Moroccan authorities, meanwhile, has so far been unsympathetic. The country’s UN ambassador Mohamed Aujjar has urged Lmrabet to contest what he labelled an “administrative decision” in Morocco, telling AFP that “you don’t get your papers by staging a hunger strike”. Lmrabet, on his part, is unwilling to risk being stranded in Morocco without papers and the ability to work or leave the country. “No one trusts the judical system in Morocco,” he said.

Feliu says it’s difficult to know what the outcome will be, but that Lmrabet is convinced this is the only way to protest. And he remains hopeful.

“He is very convinced of his fight. He is very convinced of his cause. He says that he has the moral to do it.”