In an enormous breakthrough for those seeking accountability for the shadowy surveillance industry, the Swiss Government has been forced to publish the list of export licenses for surveillance technologies and other equipment, including details of their cost and destination.

This statement was originally published on privacyinternational.org on 14 January 2015.

By Kenneth Page

In an enormous breakthrough for those seeking transparency and accountability to the shadowy surveillance industry, the Swiss Government has been forced to publish the list of export licenses for surveillance technologies and other equipment, including details of their cost and destination.

The decision by the Federal Information and Data Protection Commissioner comes on the heels of consistent pressure from Privacy International, Swiss journalists, and several Members of Parliament on policymakers, government officials, and companies in Switzerland over the past year and a half. The commissioner’s decision was the result of a FOI challenge filed against the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) for its refusal to reveal information regarding the destination of the pending exports for surveillance technologies.

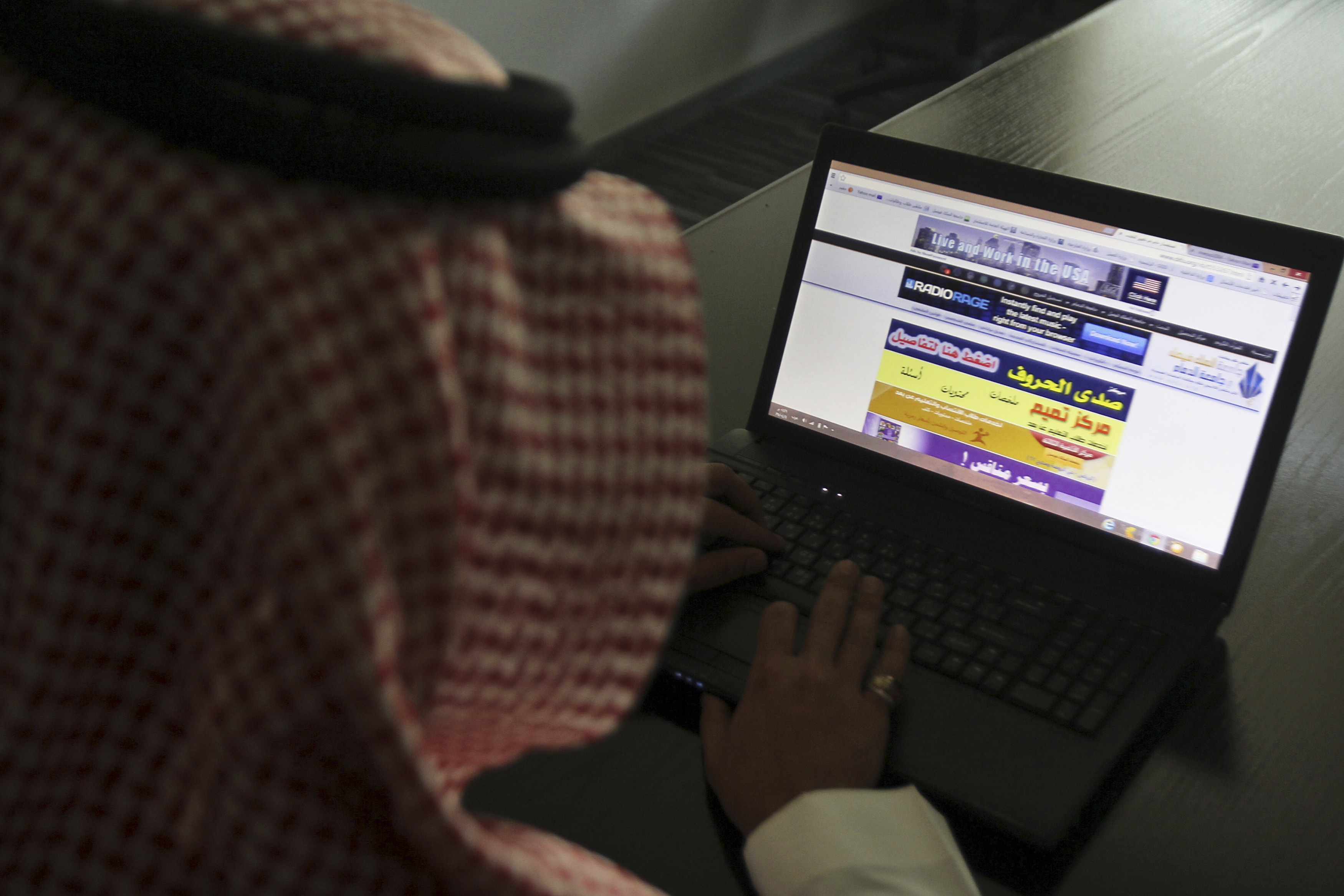

According to the now-public documents, mobile phone surveillance and internet monitoring technologies were the main equipment either being sold or attempted to be sold by Swiss surveillance companies. Twenty one export licenses were granted for IMSI catchers in 2014, and were destined for countries all over the world, including Ethiopia, Indonesia, and Thailand, for a total cost of 8 million CHF (£5.2 million). Fourteen countries, including Ethiopia, Yemen, Malaysia, Russia, and Turkmenistan, attempted to buy internet monitoring equipment, but these requests were ultimately retracted due to the higher level of scrutiny paid on the industry in Switzerland.

Privacy International welcomes this decision and hope that other countries take similar steps for greater transparency. For four years, we have campaigned against the destructive surveillance industry, and the companies selling mass and intrusive spying technologies which enable and empower repressive regimes. This latest development is a prime example of using export control reform as a tool to generate greater governmental transparency and accountability for its actions.

What was found

In its decision, the Commissioner cited the amount of media attention paid to the topic and that a recommendation should be given in favour of transparency. Privacy International rang the alarm on Swiss exports of surveillance technologies based on initial mid-2013 reports of pending licences for surveillance technology. Our work was widely reported in Swiss media, TV, print and online, including the main evening news on RTS , the daily Tagblatt, Beobachter, and a host of others.

According to the documents now published, SECO granted 21 licences for the export of the mobile phone interception technology IMSI catchers in 2014. Although attempts were made to block the release of the information on grounds of federal data protection and that the knowledge would impair the foreign policy and international relations of Switzerland, SECO has been forced to reveal the destinations: 14 of these were for temporary export and included requirements for re-entry, meaning they were likely used for trade shows (such as the “Wiretappers Ball”) or other demonstrations and exhibitions, but seven IMSI catcher licences were for definitive export. We know now that IMSI catchers were destined for Ethiopia, Indonesia, Qatar, Kuwait, Lebanon, Lithuania and Thailand for a total cost of 8 million CHF (£5.2 million).

In early 2014 several companies withdrew their licences for internet monitoring as well as several, but not all for mobile phone monitoring, following the media spotlight in late 2013, questions raised by Swiss Members of Parliament, and the refusal of the Government to make a decision on the licences, For the very first time, SECO has now been forced to release under Freedom of Information, that the retracted requests were destined for Ethiopia, Indonesia, Yemen, Qatar, Malaysia, Namibia, two licences for Oman, Russia, Chad, Taiwan, Turkmenistan, UAE, and China.

The Swiss Government has said that in general a poor human rights record or a lack of press freedom are not enough to deny the licences. However we see the continued attention paid to the issue in late 2014, with the revelation the notorious Bangladeshi “death squad”, the Rapid Action Battalion, were in Switzerland to either purchase or receiving training in surveillance technologies from the Swiss company Neosoft and the sparking of the subsequent legal investigation.

A sea-change

The result of PI’s advocacy, combined with persistent investigative reporting, has been a sea-change in transparency from the Swiss Government on its export policy, and not only surveillance technology or dual use goods. Before now, the Swiss Government has only ever published information on exports of Swiss-defined “War Material”, and some small and lights weapons. This justification will now also be used to examine exports, destinations, amounts, and dates of Swiss exports of a range of missile, nuclear, and military material.

Those calling for greater control of the export of these technologies, either through the Wassenaar Arrangement or through national and EU level controls, know that regulation on its own will not prevent a government from approving their export. Export controls are the bare minimum in providing a level of transparency that is badly needed if governments are to be held to account and to justify their decisions to knowingly export such material to end users with appalling human rights records. This will be the next step for Switzerland as undoubtedly an examination will need to take place on how exactly the previously unpublished details of such an export policy aligns to the public facing pro-human rights obligations and reputation of Switzerland.

However, there are also examples for other exporting governments to follow. Publishing reports of broad categories under which multiple technologies may fall does not allow for proper oversight or even a fair risk assessment from external experts. The devil is in the details, and the specifity provided by the Swiss Government in the number of licences approved and withdrawn for specific technologies i.e in this case IMSI Catchers, should be adopted wholesale. Governments should not shy away from openness, and resort to defending bad policies based on flimsy reasons of damaging ‘foreign policy’ or data protection for the surveillance companies.