In commemoration of the International Day to End Impunity, SEAPA highlights cases from Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, to emphasise the different responsibilities of states in ending the culture of impunity.

Follow-up report on six cases of impunity and the role of the state in Southeast Asia

Since fellow free expression advocates agreed to mark 23 November as the International Day to End Impunity (IDEI) beginning in 2011, SEAPA has highlighted a number of cases to emphasize that the culture of impunity persists throughout the region.

In practice, SEAPA’s campaign has focused on cases of impunity – which means the absence of punishment – for acts of violence against journalists and activists, and on cases repeated state violations of international law protecting the fundamental right to freedom of opinion and expression.

Perpetrators escaping culpability for acts of violence against free expression and against the media is a serious problem throughout the region, whether in free or tightly controlled media environments. Generally, states have been unable to deliver justice for the overwhelming proportion of the incidents of violence against the media and free speech, whether committed by state or non-state actors.

For example, the unsolved 1996 killing of Indonesian journalist Fuad Muhammad Syafruddin, also known as “Udin”, is due to expire in August 2014 after the statute of limitations for acts of murder expires.

At the same time, state sanctions against acts of free expression are a blunt and forceful way of suppressing opinion and speech. Moreover, each state violation – which is essentially the use of government’s might – sends the message to citizens the state will only accept acquiescence and wants to suppress dissent.

For the 2013 commemoration of the IDEI, SEAPA has chosen to focus on the role of the state both in fostering the culture of impunity and to emphasize the necessity of a systematic official response to ending this culture.

Below, we share updates on what happened in 2013 to six impunity cases that SEAPA has highlighted in its alerts and campaigns in the past years: the Ampatuan massacre in the Philippines, the imprisonment of broadcaster Mam Sonando of Cambodia and blogger Dieu Cay of Vietnam, the deaths of Cambodian journalist Heng Serei Oudom and Italian photojournalist Fabio Polenghi in Thailand, and the disappearance of Laotian development worker Sombath Somphone.

All of these cases occurred before 2013, with the disappearance of Sombath Somphone being the last incident presented in this article. Each case highlights an important aspect of the role of the state in ending impunity.

Ampatuan Massacre: Speedy, effective justice mechanisms

Four years after the incident in the Philippines, a remaining four of the detained suspects in the massacre have yet to be arraigned for their roles in the gruesome incident. The last court activity happened on 2 October, when two of the principal suspects pleaded “not guilty” to 58 counts of murder during their arraignment.

This stage of the legal process means that the court cannot even begin to hear the evidence to establish the guilt of 105 suspects currently under arrest. A total of 194 people stand accused in the Ampatuan massacre trial, but the remaining 89 have yet to be arrested.

Defence lawyers have placed obstacle after obstacle using the Rules of Court to delay the process that at this rate may take decades to complete.

The Ampatuan massacre on 23 November 2009 is believed to be the worst single act of violence committed against media workers, which included 32 of the 58 victims of the incident related to elections. The incident is emblematic of the unbridled power of some local government executives in maintaining power and control in their jurisdiction. The Philippines press is recognized to be one of the freest in the region, and impunity for violence against the media is perhaps its biggest threat.

Fabio Polenghi killing: Accountability of the armed forces

On 29 May 2013, a Thailand court inquest ruled that the bullet that killed news photographer Fabio Polenghi came from the direction of government soldiers during military operations to disperse protracted anti-government protests in 2010. The ruling marks significant progress in the quest for justice for Fabio. However, it is not clear how the case will move forward from this point.

So far, not one soldier or military unit has been charged for any culpability for Polenghi’s or any of the civilian deaths during the dispersal operations.

Murder charges have been filed by the current government against former prime minister Abhisit Vejjajiva and his deputy Suthep Thaugsuban for ordering the use of force in dispersing the protests in which Polenghi was killed. However, these charges are among those included in the controversial amnesty bill, which aimed to absolve all criminal charges related to the political deadlock beginning in 2004.

Fabio Polenghi was killed on 19 May 2010 while covering the violent dispersal of the red-shirt protests. Polenghi and a companion were shot at despite being clearly identified as journalists. He was one of over 90 persons killed – mostly protesters but also including soldiers and another journalist – during this tumultuous period in Thailand politics.

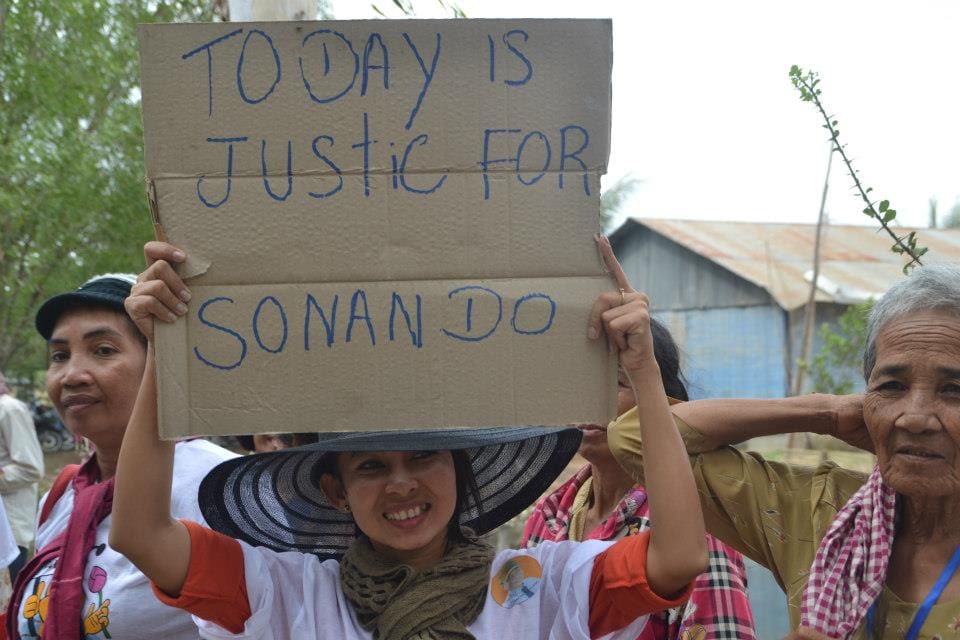

Mam Sonando imprisonment: Rule of law

The saga of the unjust imprisonment of independent radio station owner Mam Sonando ended on 14 March 2013 when the Cambodian Appeals Court reduced his 20-year sentence to a five-year suspended sentence.

His freedom was the result of an unexpected move on 7 March by the prosecutor, who requested the court to drop the most serious charges of insurrection and incitement to secession against Mam Sonando and his co-accused. These were the same charges for which Mam Sonando was sentenced in October 2012, sparking a huge outcry from the international community which had called these charges spurious and fabricated.

In its place, the lesser charge of obstruction of law enforcement was retained, and an additional charge of “illegal logging” was filed. One week later, Mam Sonando was free. It is not clear whether the new charge against him has any basis as well.

Mam Sonando’s case is significant for reflecting the extent of steps which the Cambodian government is willing to take to silence its critics. Mam Sonando was jailed by authorities immediately upon his return to the country in July, after his radio station aired the filing of a case against the government in the International Criminal Court. State authorities linked him to a violent confrontation related to a land conflict in Kratie province, and accused him of leading villagers to secede from the state.

Heng Serei Oudom murder: protection of journalists

Despite the generally positive outlook in 2012 for the killing of Cambodian journalist Heng Serei Oudom, it appears that his case will end up like the majority of cases of violence against journalists in the region.

On 29 August 2013, a Cambodian provincial court dropped the charges against the two primary suspects in the case due to lack of sufficient evidence.

This is a drastic turn from the situation one year ago, when a judge declared that the investigation of main suspects was ‘finished’ and charges had been filed against two main suspects, military police captain An Bunheng and his wife. It appeared then that the killing of Heng Serei Oudom would be one of the few cases that would receive justice.

Court prosecutors declared in 2012 that they had found evidence linking the suspects to the murder of the journalist; he was found bludgeoned to death inside his car two days after he went missing on 10 September 2012.

The turn of events from the 29 August verdict surprised the journalist’s family, and media and environmental groups who were pushing for justice.

Heng Serei Oudom, a reporter from the Ratanakiri-based Vorakchun newspaper, was investigating the role of the military police in illegal logging and timber smuggling in the province. His last article, published four days before he went missing, linked the son of a military police official to illegal logging in the province.

Dieu Cay imprisonment: respecting dissenting opinions and actions

Renowned Vietnamese blogger and political prisoner Nguyen Van Hai, also known as Dieu Cay, staged a five-week hunger strike beginning in June to protest the lack of response to his complaint of maltreatment during his imprisonment.

In his case, prison authorities allegedly put him in solitary confinement for three months after he refused to sign documents confessing guilt for the charges on which he was convicted in September 2012.

Because of this mistreatment, Dieu Cay sent a complaint to the Provincial Procuracy in Nge Anh. After receiving no response, he began his hunger strike to draw the attention of the authorities to look into the case of abusive treatment. Family members told the media that Dieu Cay wanted to draw attention to the continuing harassment of imprisoned bloggers and activists.

Dieu Cay ended his hunger strike on 27 July after judicial authorities agreed to look into his complaint.

Dieu Cay and two other prominent bloggers were sentenced on 24 September 2012 on charges of conducting propaganda against the state. Their respective sentences were upheld on appeal on 28 December.

Sombath Somphone disappearance: regional co-responsibility for human rights

Renowned Lao development worker Sombath Somphone has been missing since 15 December 2012. Despite global concern regarding his disappearance, Sombath remains missing with the Lao government having little to show in terms of progress or leads regarding his case.

His disappearance occurred about two months after a rare international civil society meeting in October 2012 called the Asia Europe People’s Forum, in which Sombath played a major role as one of the organisers. The meeting was one of the few opportunities for Lao communities to publicly raise issues they confront.

Sombath was last seen on 15 December, when he was forcibly driven off in his vehicle by an unidentified man after being stopped at a police checkpoint.

Appeals to find Sombath include those coming from regional and international civil society as well as delegations of parliamentarians from Southeast Asia and Europe. Despite this pressure, the Lao PDR government investigation into the case has failed to produce any credible explanation for the disappearance.

Sombath’s case is significant for the region not only because of the recognition he has received in his work – for example as a Ramon Magsaysay awardee in 2005 – given the limited space for civil society to operate in Laos. Community development is the only area of NGO activity allowed in Laos, and is a major channel for international development assistance to Laos.

Sombath’s case is also the first case of an enforced disappearance in the region since governments in ASEAN adopted the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, the first regional human rights instrument in Asia, on 18 November 2012. The AHRD also includes a prohibition against abduction (Article 12). The regional document has not changed the way Southeast Asian countries handle human rights issues: by treating these as internal issues of ASEAN members.

Week-long commemoration of the International Day to End Impunity

On 18 November, SEAPA launched its week-long commemoration of the IDEI.

The highlight of the campaign will be a brief discussion of the situation of impunity in the region with UN Special Rapporteur on right to freedom of opinion and expression Mr Frank La Rue, on 23 November at 11:30 a.m.

The campaign can be tracked through SEAPA’s website, and social media accounts in Facebook and Twitter (@seapabkk).