"In 2024, the same year democracy levels hit their lowest point since The Economist's Democracy Index was created in 2006, RSF noted that journalists’ work was increasingly obstructed by political forces."

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 15 September 2024.

Press freedom is not just a fundamental pillar of democracy, but a measure of its vitality. For the International Day of Democracy on September 15, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) compared the results of its World Press Freedom Index with the Democracy Index by the British press group The Economist.

The correlation between democracy and press freedom is obvious – and proven. A comparison of the assessments of 167 countries made by RSF’s 2024 World Press Freedom Index and The Economist‘s annual Democracy Index shows the two values are empirically linked.

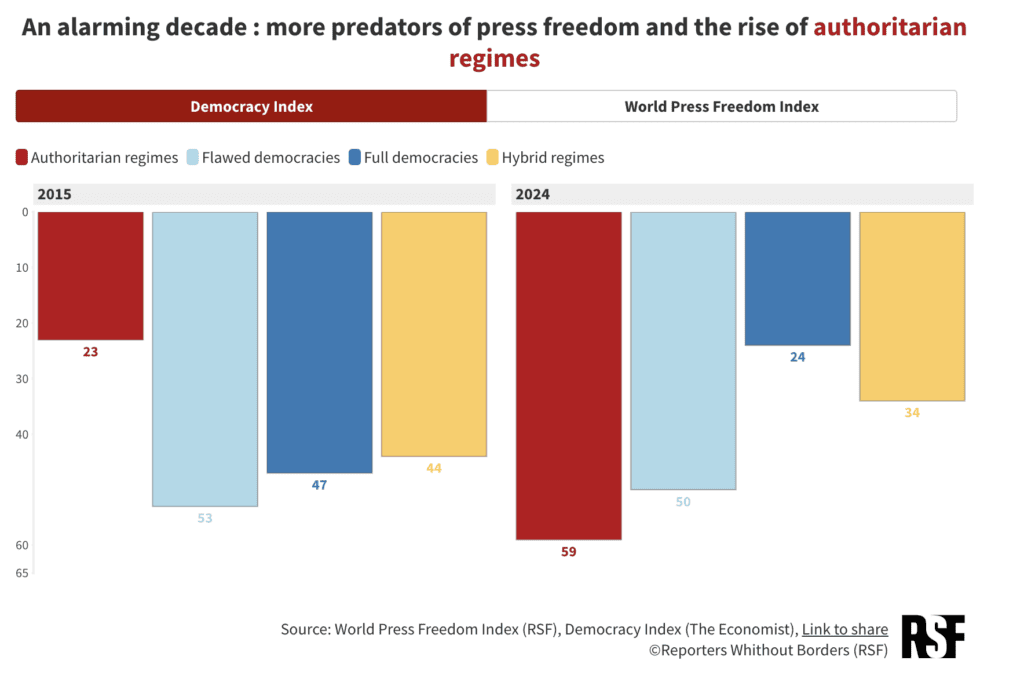

Over the last ten years, RSF’s press freedom map has gradually turned red, just like The Economist‘s Democracy Index. In the span of a decade, 16 countries have seen their press freedom situation become “very serious,” and 36 countries have come under the yoke of authoritarian governments. Ten of these countries – Palestine, Iraq, Egypt, Pakistan, Burma, Cambodia, Russia, Belarus, Venezuela and Nicaragua – turned red in both rankings, as the color designates both very serious press freedom situations and authoritarian regimes.

In 2024, the same year democracy levels hit their lowest point since the Democracy Index’s creation in 2006, RSF noted that journalists’ work was increasingly obstructed by political forces. Of the five indicators in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index, the political indicator is deteriorating the fastest.

“Press freedom acts as a mirror reflecting the vitality of democracies around the world. Political forces that do not guarantee the media’s independence jeopardize the foundations of democracy. RSF, therefore, insists on the need to fight disinformation – a symptom of democracy’s erosion – by implementing ambitious policies to promote reliable information, journalists’ protection and the right to information.”

Blanche Marès, Data Journalist and Head of RSF’s World Press Freedom Index

An alarming decade for democracy and press freedom

In 2024, there are almost half as many “full democracies,” i.e. democracies with only minor problems in their functioning, as in 2015 (24 in 2024 compared to 47 in 2015), and three times fewer countries with a “good” press freedom situation (8 in 2024 compared to 26 in 2015).

Over 85% of journalists detained worldwide are imprisoned by authoritarian regimes. The 59 countries labeled “authoritarian regimes” by the Democracy Index, places where the state exercises direct control over the media and criticism of the authorities is dangerous, hold over 500 journalists, including 111 detained in China, 61 in Burma, 42 in Belarus, 40 in Russia, 37 in Israel and Vietnam, 25 in Syria and Iran.

Bangladesh, Honduras, Bhutan and Turkey: four “hybrid” regimes that curb press freedom

In the vast majority of corrupt, undemocratic regimes – dubbed “hybrid” by The Economist – pressure on the media is intense, and journalists are frequently killed or imprisoned for their work.

This violence is particularly frequent during election periods, as was the case in Turkey (currently ranking 158th out of 180 countries in RSF’s Index), where 43 journalists went to prison in 2023. Impunity is commonplace in Honduras (146th), which remains one of the most dangerous countries in Latin America for journalists, and Bangladesh (165th), where three journalists were murdered in 2023. In Bhutan (147th), a country that has dropped in RSF’s Index, press freedom remains fragile despite being enshrined in the 2008 Constitution.

Some “hybrid” regimes in the top quarter of RSF’s Index, such as Armenia (43rd), Fiji (44th), and Mauritania (33rd), show that even within political systems that are not fully democratic, improvements in press freedom are achievable.

Press freedom: the “antidote to tyranny”

Conversely, countries with a “good” press freedom situation are all democracies (classified as “full” and “flawed” democracies). Democracies that respect the rule of law and checks and balances encourage freedom of information and stand in the way of authoritarianism. This finding is highlighted in “Press freedom: the antidote to tyranny,” an episode from the program “Le Dessous Des Cartes” by the European TV channel Arte, which gives a detailed look into the 2023 World Press Freedom Index.

Of the 24 countries with a fully-fledged democracy, a quarter have a “good” press freedom situation. They are the six countries at the top of RSF’s Index: Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands and Ireland.

Five “full” democracies with press freedom problems

Five of the 24 “full democracies,” however, are not on the higher end of press freedom scores (classified as “good” or “satisfactory”). The Economist reports that In Greece (88th), press freedom violations plague democracy. This year, Greece, the cradle of democracy, returned to the category of “full democracies” for the first time since 2010, yet remains the European Union’s lowest-ranked country in the Press Freedom Index. This is due, in part, to the fact that political forces in Greece use criminal prosecution for defamation as a means to pressure journalists.

In Japan (70th) and South Korea (62nd), two rare cases of “full democracies” in Asia, economic interests, political pressure and threats of defamation lawsuits prevent journalists from fully exercising their role of keeping power in check. Mauritius (57th) may be hailed as a model of democracy in Africa, but its media landscape is highly polarized. Similarly, Uruguay (51st) has a political climate conducive to dialogue on the role of the media, yet media ownership is highly concentrated.

“Flawed democracies”: press freedom as a means for improvement

A free press enables a democracy to examine itself, correct its shortcomings and perpetually improve. This is why “flawed” democracies – which, despite free elections, have shortcomings in their political institutions or culture, and have widely varying degrees of press freedom (ranging from “very serious” to “good” in RSF’s rankings) – need to use press freedom as a tool to strengthen their democratic standing.

This is particularly true in India and Sri Lanka, two extremely hostile environments for journalists that currently hold their worst scores since 2014 in the Press Freedom Index.

India (159th) is stagnating at an unacceptable ranking for a democracy. In April, RSF issued ten recommendations to the political parties participating in India’s general elections. Since Narendra Modi came to power in 2014, repression against journalists and the media has increased; at least 28 journalists have been killed and nine imprisoned, notably through the instrumentalization of anti-terrorism laws.

In Sri Lanka (150th), the political situation has been extremely volatile since the protests that shook the island in 2022. Journalists working on issues related to Tamil or Muslim minorities risk arrest, coordinated cyberattacks and death threats.