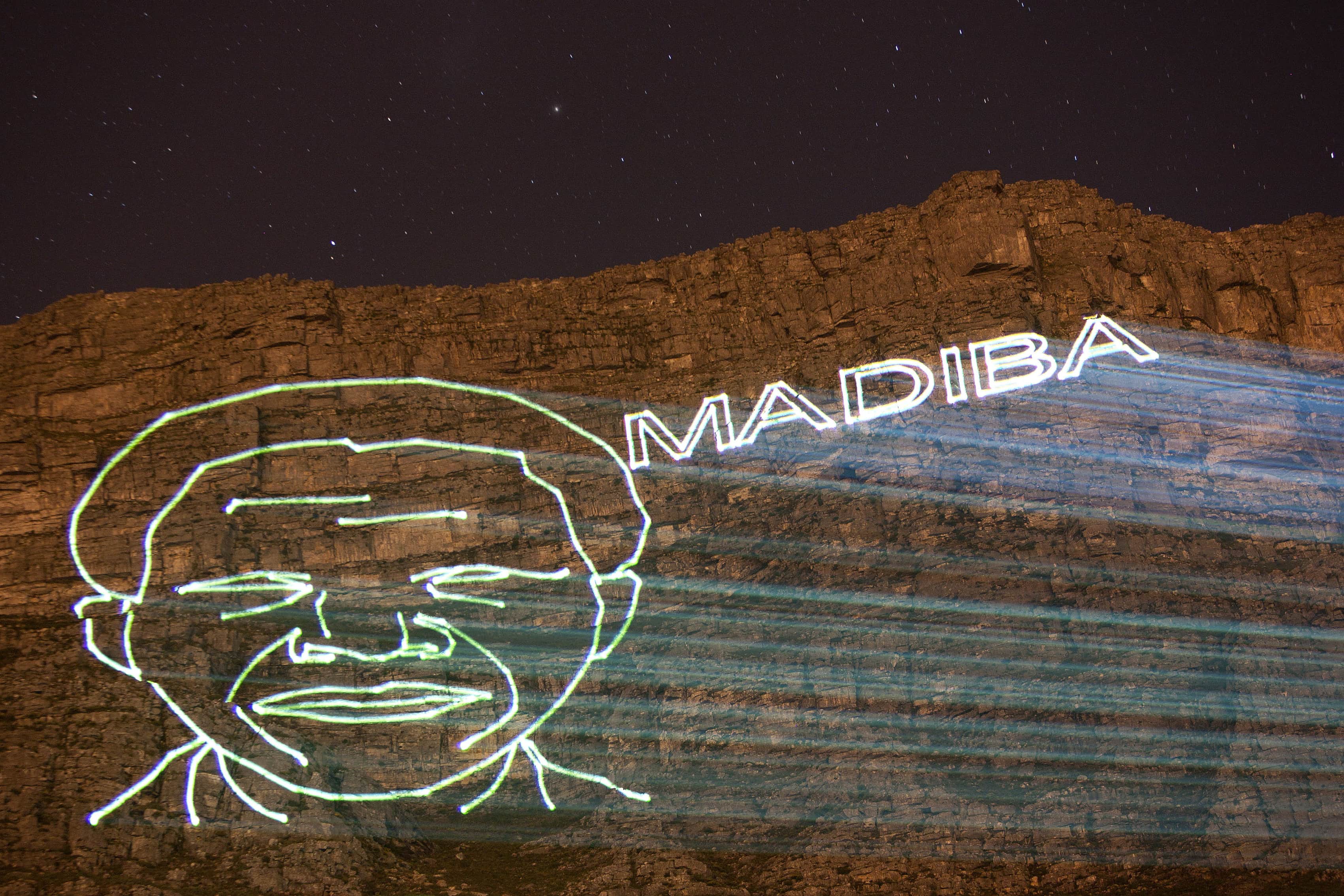

Last month the world lost a great leader, statesman and human being. While Nelson Mandela will never be forgotten, particular attention must be paid to the gains in human rights and free expression that have been made in South Africa, in large part due to Mandela's influence.

By Heidi Fortes

Last month the world lost a great leader, statesman and human being. While Nelson Mandela will never be forgotten, particular attention must be paid to the gains in human rights and free expression that have been made in South Africa, in large part due to Mandela’s influence.

South Africa has made an impressive transition to democracy over the past few decades, which could not have come to fruition without the dedication of those who continue to push for freedom of expression and press freedom. The transition from outright censorship to a newfound openness in the media has been rather remarkable when taking South Africa’s oppressive history into consideration.

Propaganda and censorship were regular tools used by the South African government during apartheid to justify its oppressive policies. From 1948-1994, the government stripped its black citizens of basic rights and economic freedom, and restricted their mobility within the country. The regime was particularly effective in its control over the media, which encompassed print, television and radio.

In 1976, the Soweto Youth Uprising fueled the anti-apartheid movement and became one of the bloodiest instances of racial violence since the 1960 Sharpeville massacre. During the 1976 uprising, police opened fire on 10,000 students peacefully marching in protest of a government directive making Afrikaans a compulsory language of instruction in township schools. Afrikaans was seen as the “language of the oppressor” by many black South Africans, who thus objected to its imposition in the education system. Soweto was barricaded by police, while journalists attempting to report on the protest were turned away by then senior military official Brigadier R Le Roux. As the violence spilled over, police barricaded six other neighbouring townships, further preventing journalists from reporting on the crisis. When the uprising was later reported in the mainstream media, it was described as anarchic and criminal, ignoring the main cause for the protest and the many deaths of black students.

In 1977, the regime exercised its authority over the media yet again when it forced white anti-apartheid journalist Donald James Woods into exile. Woods, editor of the Daily Dispatch from 1965-1977, was well known for speaking out against injustices against minorities. He defiantly hired black journalists to the Daily Dispatch, and openly provided political support to prominent black activist Stephen Biko. In 1977, Biko died in police custody; the cause of death was reported as a hunger strike. However, Woods published photos of Biko’s battered corpse, exposing his death as a cover up by the government. Woods was subsequently placed under a five year ban, which amounted to being placed under house arrest; he was forbidden from writing, publishing, or campaigning in South Africa.

A year later, Woods fled South Africa after being stripped of his editorship, and experiencing threats towards himself and his family. He continued to advocate against apartheid from abroad, living in London, and finally returned to South Africa in 1994.

The years following Mandela’s release from prison in 1990 marked an optimistic time for the once suffocated South African press. The shift to democracy meant that freedom of expression was at the forefront of the newly liberated minority communities. This freedom resulted in the creation of organizations to safeguard the diversity and transparency of the press from the grips of a ruling party – such as the Independent Broadcasting Authority and The Media Development and Diversity Agency. The pinnacle was reached in 1996 with the adoption of the new constitution, which included a Bill of Rights guaranteeing media freedom, freedom of expression and access to information.

During this time, the press was highly regarded as a tool by which South Africa could reconcile its previously divided population and become a more connected nation. The promotion of reconciliation continued post–Mandela, but there was also a newfound sense of responsibility in the press to hold the government accountable and expose corruption.

In 2013, the South African media’s ability to fulfill its role as watchdog was severely threatened when the Protection of State Information Bill was introduced. The Bill would allow any “organ of the state” to make its documents classified. This ability would also extend to information pertaining to commercial interests, if it was deemed to be connected to the “national interest,” a term left without a clear definition. A journalist or whistleblower found to have unlawfully disclosed classified information would be subject to charges of espionage, with the penalty reaching up to 25 years in jail.

Many prominent South African figures have voiced their disapproval of the Bill, including Desmond Tutu who described it as “a dark day for freedom of expression,” and stated that it would “outlaw whistle blowing and investigative journalism.” In April, 2013, after undergoing several amendments, the “secrecy bill,” as it came to be known, was approved by Parliament despite still being widely criticized for its lack of protection for the public interest. Surprisingly however, in late 2013, President Jacob Zuma refused to sign the Bill and sent it back to Parliament for further revisions.

While President Zuma’s reluctance to sign a bill threatening freedom of expression is perhaps a positive action, it is important to note that the president has taken issue with artistic freedom in the past. In May 2012, Zuma and the ruling ANC party attempted to have a painting of the president removed from the walls of a Johannesburg gallery and subsequently destroyed after Zuma took issue with the style of his portrayal.

Regardless of politics, the resilience of the South African press to protect its own independence and promote democratic transparency is commendable. Although the country still has substantial room for improvement in terms of protecting its journalists and guaranteeing access to information, it is important to take President Mandela’s passing as an opportunity to reflect on the growth of South Africa’s free press in the post-apartheid era.

Heidi Fortes (@HeidiFortes) is an economics and political science graduate of McMaster University and a freelance writer in Toronto.