Singapore's mainstream media revolves more around educating people along official narratives rather than serving as a Fourth Estate. But as citizens increasingly turn to the Internet as their source of news and information, websites and blogs are making an unmistakable impact on Singapore's media landscape.

By Kirsten Han

Speaking in a Singaporean university seminar room in early March 2014, Lord David Puttnam highlighted the importance of media plurality. He saw it as a means to an end, a way to foster an informed citizenry in a society where no one person or entity has too much influence over the media.

It was an interesting location for him to be talking about media plurality. Thanks to the laws and regulations establish by the People’s Action Party government – the party’s rule has been uninterrupted since Singapore achieved self-governance in 1959 – the country has not had true media plurality for a long time. Most mainstream media organisations are owned by government-linked corporations, and the government also has the power to appoint management shareholders to newspaper companies.

This has resulted in a mainstream media that revolves more around educating Singaporeans along official narratives rather than serving as a Fourth Estate. But as Singaporeans increasingly turn to the internet as their source of news and information, websites and blogs are making an unmistakable impact on Singapore’s media landscape.

The Online Citizen (TOC) is a notable example. Launched in 2006, the website is unabashedly political in a country where the subject of politics is often approached with trepidation. “Our specialty is in reporting on social issues and government policy. We tend to focus on cases where policy has affected people in ways that you will not see touted in mainstream media, and we try to increase our readers’ perspective on these issues, so they can think about the way forward,” the TOC core team wrote in an email to Index.

The issues that TOC has covered vary from poverty and homelessness to the exploitation of migrant workers. Commentaries have examined numerous state policies, from public housing to media regulation. It was also one of the major alternative websites that covered the 2011 general Election – the first election in which online and new media was prevalent.

Since then, several new platforms have emerged. They cover a spectrum, from New Nation’s satirical humour to The Independent Singapore’s attempt to bring non-mainstream professional journalism to the online sphere. This blossoming of online websites has been accompanied by parallel discussions on social media platforms, especially Facebook and Twitter. Where Singaporeans once only had establishment-dominated mainstream media voices to tune in to, alternative perspectives, criticism and discussion are now common online.

The threat the online community poses to the government’s hegemony has not gone unnoticed. Government figures have said plenty about the dangers of the internet, going so far as to label it a threat that could hamper Singapore’s Total Defence strategy. An acronym, DRUMS, was invented. It stands for Distortions, Rumours, Untruths, Misinformation and Smears.

Defamation suits and warning letters from lawyers have also been issued to various blogs and websites. The Attorney-General’s Chambers is now trying to take legal action against prominent blogger Alex Au, accusing him of having “scandalised the judiciary” – the same charge that British journalist Alan Shadrake faced in 2010.

Legislation has also been invoked to exert some control (or at least influence) over the internet. In 2011, TOC was gazetted by the prime minister’s office as a “political association”. This meant that TOC would not be able to receive any foreign funding, and that anonymous donations made to the website had to be limited to S$5,000 (£2,377) a year. Once that amount is reached, anyone who would like to donate will have to be identified.

The move has limited TOC’s ability to fund its work. “Classifying us as a political website gives potential investors the impression that TOC is aligned with partisan politics, where the truth is we do not align ourselves with any political party. Such an impression has an impact in terms of encouraging people to donate to the website,” TOC explains.

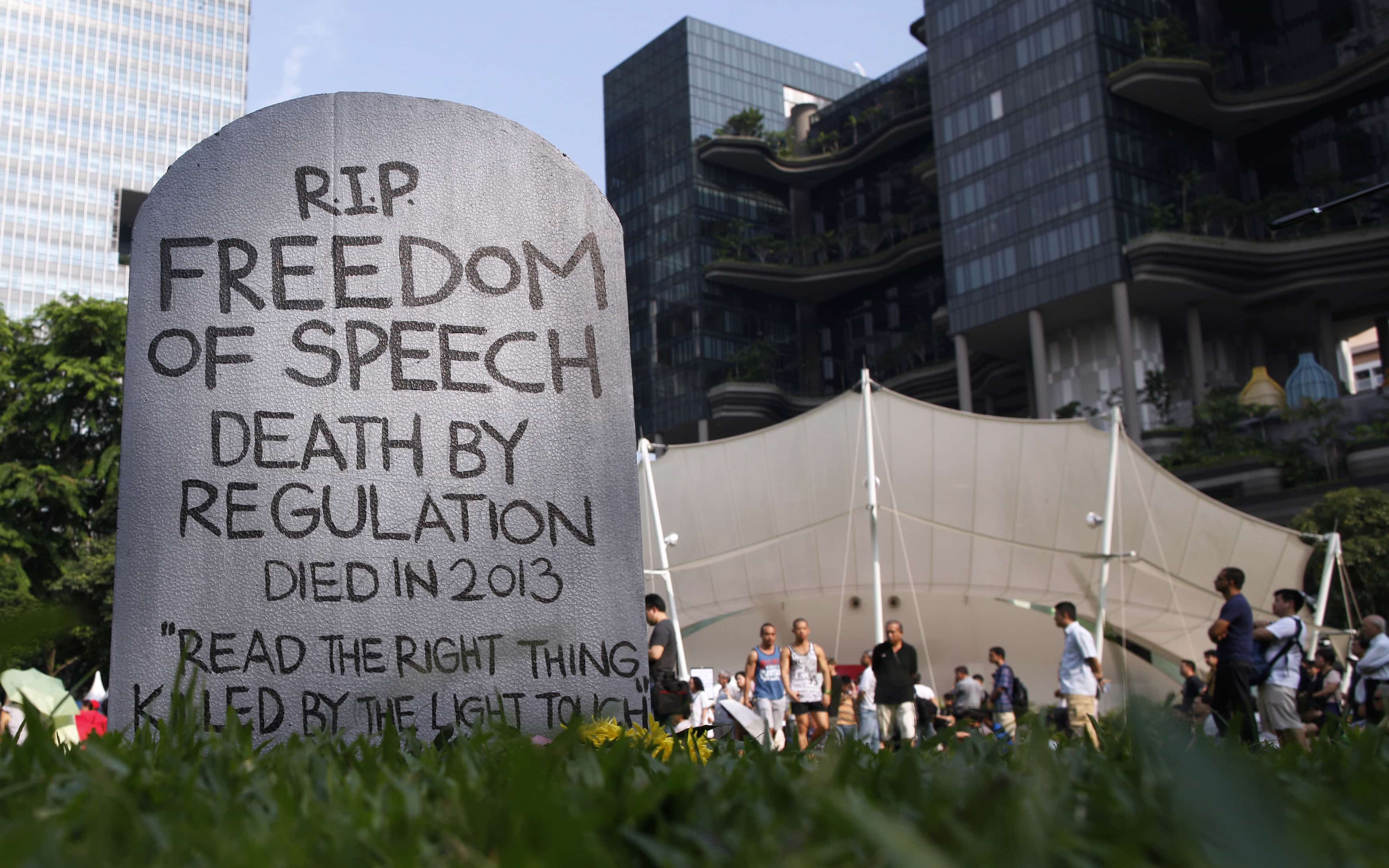

But TOC is not the only website to have felt the government’s “light touch” on the internet. In 2013 the government announced a new licensing regime: popular news websites – defined as those that receive more than 50,000 unique visitors a month – would need to get licenses from the Media Development Authority. They would be required to put down a S$50,000 (£23,772) bond and commit to taking down any material deemed in breach of content standards within 24 hours.

The regime was put in place very quickly, and ten websites were identified for licensing. Only one – Yahoo! Singapore’s news website – was not a website owned by Singapore’s mainstream media corporations and already regulated under other legislation. The government said that blogs would not be licensed under these rules, but citizen journalists are not so sure. After all, the MDA defines “news reporting” as “any programme (whether or not the programme is presenter-based and whether or not the programme is provided by a third party) containing any news, intelligence, report of occurrence, or any matter of public interest, about any social, economic, political, cultural, artistic, sporting, scientific or any other aspect of Singapore in any language (whether paid or free and whether at regular interval or otherwise) but does not include any programme produced by or on behalf of the Government.” The definition is more than broad enough to encompass the work done by some blogs.

Outside of the licensing regime, three other alternative websites have since been singled out for registration with the MDA. Registering with the MDA requires a website to make all its editorial staff known to the regulators, as well as declare that it will not receive any foreign funding.

The Breakfast Network was asked to register late last year. It chose to shut down instead.

“We didn’t like the idea of being ‘registered’. We started as a pro bono site and some of us didn’t think it was any business of the government to have details of who was doing what,” wrote its former editor-in-chief Bertha Henson in response to Index on Censorship.

The other two websites, The Independent Singapore and Mothership.sg, decided to comply and register. They say that they have never received any foreign funding anyway, and so it’s not made too much of an impact on operations.

“I’m very open with the MDA. I tell the MDA what I do, so they don’t get overly concerned and suspicious and try to shut us down,” said Kumaran Pillai, chief editor of The Independent Singapore.

The restriction of foreign funding might cut off some funding streams for online websites, but Singapore’s blogosphere continues to grow. With the next general election (which has to be called before mid-2016) coming up, alternative websites are getting prepared. Both TOC and The Independent SG are building up to the election. But will establishment sources be willing to engage in their attempts at providing alternative coverage?

“If they won’t give us the press releases, it’s their loss,” Pillai said with a shrug. “They are going to lose out in the long run.”

This article was originally posted on 23 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org