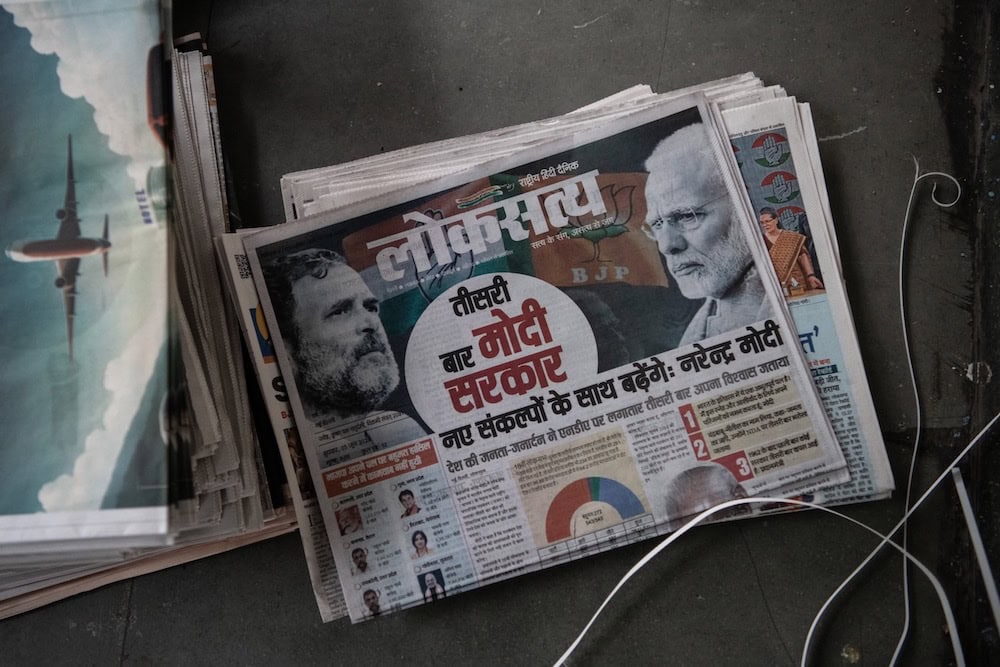

IPI global network noted that press freedom has deteriorated dramatically under the first two terms of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

This statement was originally published on ipi.media on 3 July 2024.

IPI urges PM Narendra Modi to honour his commitment to freedom of the press

As Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi assumes his third term, the IPI global network calls on his administration to honour commitments to ruling with “true faith and allegiance to the constitution” by prioritizing freedom of the press and the safety of journalists.

Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian constitution guarantees the right “to freedom of speech and expression”, which can only be restricted to a “reasonable” extent on narrow grounds. Freedom of the press is an especially vital category of protected speech; independent and pluralistic news is essential to the function of democracy. A free and independent press enables citizens to be informed and to hold the powerful to account.

Today, IPI reiterates its call on the Modi government to take concrete steps to protect these rights, noting that press freedom has deteriorated dramatically under the prime minister’s previous terms.

A year ago, IPI outlined steps that needed to be taken to protect press freedom in India. In the past year, little progress has been made in these key areas. We therefore once again draw attention to the following issues that are undermining press freedom and threatening journalists’ ability to carry out their work freely and safely.

“Lawfare” against the press: Indian authorities have weaponized vague laws such as the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), the Informational Technology (IT) act, and a range of other legal regulations to censor journalism and media that is critical of the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Authorities have continued to use these laws to target and punish critical journalists, particularly those in Jammu and Kashmir. A significant percentage of UAPA cases filed against journalists as of April 2024 targeted journalists in Jammu and Kashmir, a region which, in terms of population, comprises less than 1 percent of India.

Lawfare, in the form of administrative harassment, has also been used to silence foreign journalists through the denial of visas or revocation of Overseas Citizen of India status (OCI). In a recent case, Avani Dias, a journalist for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, was effectively expelled from the country prior to the elections after being told by authorities she had “crossed a line” in her reporting. An open letter from 30 foreign correspondents protesting Dias’s treatment decries the difficulties created by “increased restrictions on visas and journalism permits for those holding the status of Overseas Citizens of India”. Article 14, a rights organization dedicated to legal equality in India, revealed that OCIs have been denied for voicing anti-Hindutva beliefs, “anti-Indian activities”, and “detrimental propaganda”.

Cybercrime laws as a means of censorship: The Information Technology Amendment Rules, 2023, grants authorities the right to “remove any online content pertaining to its business that it deems to be false or misleading”. Such broad language as “pertaining to its business” has a chilling effect on journalists, as it is unclear what can and cannot be prosecuted. Dissident voices, whether individual journalists or entire publications, have had their social media accounts censored or websites blocked. As is the case with much of the press repression from Indian authorities, religious minorities face disproportionately higher rates of censorship.

Internet shutdowns: India continues to shut down the internet more often than any other country in the world. Digital rights group Access Now recorded at least 116 instances of internet shutdowns ordered by Indian authorities in 2023, an alarming increase from 84 recorded instances in 2022. The right to information is a fundamental right enshrined in international and Indian law. According to the Indian Supreme Court, the right to information is an essential component of Article 19(1) of the Indian constitution.

Spyware: Amnesty International, in partnership with The Washington Post, found trace evidence that some Indian journalists had been attacked by the highly advanced spyware “Pegasus”. The evidence indicates that the most recently found attacks of the no-click spyware took place in October 2023. The surveillance of journalists – especially through spyware tools capable of sweeping up the entire contents of a journalist’s phone – represents a grave threat to source protection as well as journalist safety, and threatens to cast a chilling effect on investigative reporting.

Impunity for attacks against journalists: India ranked as the 12th worst country in the CPJ’s 2023 impunity index, which ranks unsolved journalist murders per capita. Failing to prosecute such attacks encourages a deadly cycle of violence against journalists. The Indian authorities must carry out comprehensive, transparent, and credible investigations into all attacks on journalists, and especially the killing of journalists.