Sarah Cook of Freedom House writes about the different types of information restrictions that the Beijing government might use before, during, and after the 2022 Winter Olympics.

This statement was originally published on freedomhouse.org in January 2022.

With the eyes of the world turning to China, the government is focused on dictating what they see

By Sarah Cook

As Beijing prepares to open the 2022 Winter Olympics on February 4, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership will be dialing up the world’s most sophisticated apparatus of information control, using censorship, surveillance, and legal reprisals to curb political, religious, and other speech that deviates from the party line. This apparatus has grown dramatically in the years since Beijing hosted the 2008 Summer Games. Indeed, Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net 2021 report found that China’s government was the worst abuser of internet freedom globally for the seventh year in a row, earning the country a dismal 10 points on the report’s 100-point scale.

These conditions could have serious implications for athletes and journalists and for the Chinese public more broadly. The following are five types of restrictions to watch for before, during, and after the games:

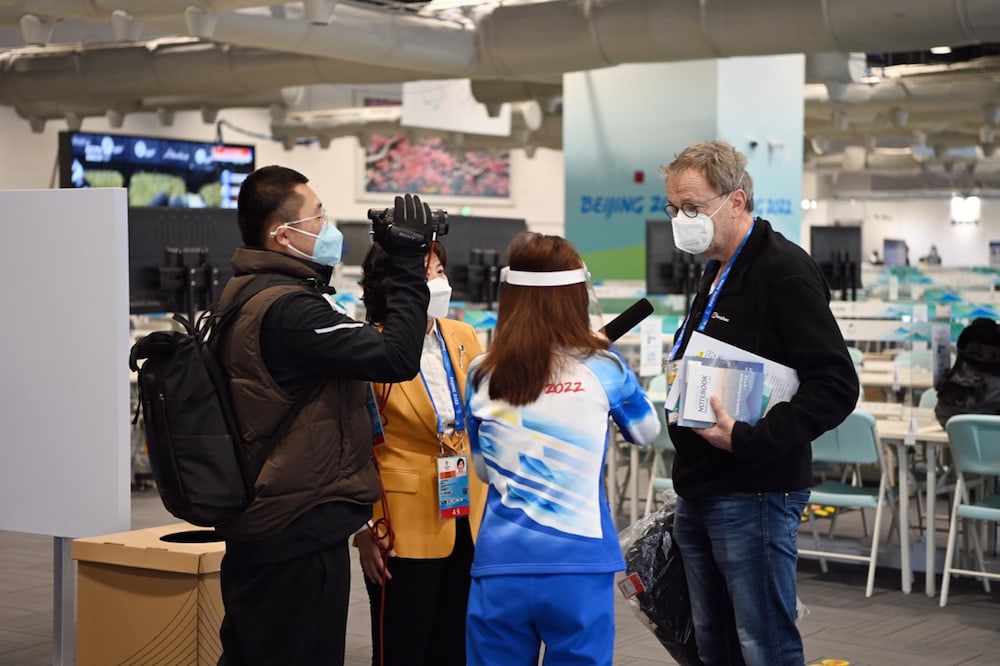

1. Surveillance of athletes and journalists

The 2008 Beijing Olympics notably served as a catalyst for upgraded surveillance, and more recently the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted further expansion. Governments and international human rights groups are already warning this year’s Olympic attendees to take precautions. The Dutch, British, Australian, and US Olympic Committees have suggested that athletes and staff leave their phones and laptops at home or offered temporary devices for use during the games to enhance security and protect personal data. Similarly, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has prepared a safety advisory for reporters, urging them to take clean personal devices to China, to open new email accounts for use during the trip, to “assume your hotel room is under surveillance,” and to “avoid installing the Chinese app WeChat … since it is likely to collect a lot of data, including messaging and calls.” On January 18, an investigation published by the Toronto-based Citizen Lab validated such concerns, finding that the My2022 app, mandatory for all attendees to install as part of the games’ COVID-19 protocols, included vulnerabilities that could facilitate exposure of personal data, such as sensitive medical information. In addition, the app carries features that enable users to report one another for sharing politically sensitive content. Such openings for surveillance on apps that ostensibly serve other purposes have been revealed in China before – including on a Xi Jinping propaganda study app and a COVID-19 health code app. It remains to be seen whether the security gaps in the My2022 app will be sealed and whether other evidence of surveillance will be exposed.

2. Reprisals for political speech and independent reporting

The presence of a user reporting mechanism in the MY2022 app highlights the regime’s nervousness about attendees speaking publicly on topics other than the sporting event itself. The Olympic Charter places some restrictions on demonstrations and political propaganda during medal ceremonies or competition. But new rules allow such expression on the field of play before competition, and athletes are free to air their views when speaking to the press or on social media platforms. During the Tokyo Games, one US athlete engaged in a protest on the medal podium, prompting organizers to announced that they were looking into potential sanctions, while two Chinese cyclists were warned over Mao badges. But in China’s legal environment, the consequences of outspokenness could be much more grave. On January 18, an official for the Beijing Organizing Committee warned of “certain punishment” for any behavior or speech that is against “Chinese laws and regulations.” This leaves open the possibility of legal reprisals not only for acts of protest at Olympic venues, but also for comments about human rights or criticism of Chinese leaders in front of the international press or on social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook, which will be accessible at Olympic venues even as they are blocked in the rest of China. CPJ also warns reporters about the use of unofficial virtual private networks (VPNs), noting that “accessing an unlicensed VPN could be used against you if officials are looking for an excuse to penalize you.” Given the international profile of the games, prosecution of an Olympic athlete seems unlikely, but an outspoken journalist or athlete could easily face expulsion. Meanwhile, local residents in mainland China and Hong Kong, who express views perceived to threaten the positive image the Chinese government wishes to portray, could face legal penalties. Last summer, Hong Kong police detained a man who booed during the Chinese national anthem when watching the Tokyo games at a shopping mall.

3. Rapid censorship of any scandals, even those unrelated to the Olympics

China’s leaders might feel compelled to quickly suppress any number of unfavorable news stories, such as revelations that Olympic attire was produced with Uyghur forced labor, athlete complaints about an Olympic venue, or unsportsmanlike conduct by a favored Chinese athlete. Censors’ responses could include interrupted television broadcasts, massive deletion of social media posts, or bans on online comments. The Citizen Lab analysis of the MY2022 app, whose functionalities include real-time chat and news feeds, found evidence of a latent censorship keyword list that flags phrases like “Dalai Lama,” “Holy Quran,” or “Falun Dafa is good,” as well as references to Chinese government agencies and Xi Jinping. The feature was inactive at the time of the investigation, but it could be activated by the Beijing Organizing Committee, especially if a protest or scandal erupts. Moreover, censors will be on high alert to quash any other unfavorable news from across China, with potentially life-threatening consequences for ordinary people. It was such instructions ahead of the 2008 Beijing Games that delayed reporting on tainted milk for infants, contributing to the death or illness of hundreds of thousands of babies. As the Omicron variant spreads, officials will also be tempted to cover up news related to COVID-19, whether it involves new outbreaks or lockdowns gone awry, and to detain those trying to share unofficial information.

4. Stonewalling foreign journalists

In addition to heavy-handed restrictions, the Chinese government is adept at using more subtle methods to obstruct or disincentivize independent reporting. Officials could simply delay invitations, invoke onerous health protocols, or fail to approve foreign journalists’ applications for access to certain events, venues, or outspoken athletes until it is practically impossible for even approved reporters to attend. Authorities might also grant Chinese state media privileged access to a given location or event, forcing international media to rely on them for coverage. A November 2021 statement by the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China relayed a sample of 10 such incidents reported by American, European, and Asian journalists when they attempted to cover preparations for the games. The journalists said they encountered access denials, filming interruptions, monitoring by plainclothes police, last-minute notifications, and verbal abuse by an official following mention of human rights boycotts in a television story about an Olympic venue.

5. Repercussions after the closing ceremony

Even if the CCP and its information control apparatus are on their best behavior during the games, there will be many opportunities for reprisals after the sporting event has concluded. For example, a journalist who reported about the Chinese government’s abuses could be denied a visa renewal, or local Chinese citizens who serve as translators or news assistants for foreign media could face criminal charges, as Bloomberg news assistant Haze Fan has since December 2020. Departing athletes, coaches, and other attendees may also begin to reveal pressure to self-censor or unsavory encounters with the Chinese police state once they feel more free to speak. Meanwhile, Chinese activists and religious believers who were quietly targeted for harassment and detention as part of the heightened security controls surrounding the games could receive formal sentences of years in prison. Already, activist Guo Feixiong and lawyer Xie Yang have been charged with “inciting subversion” this month, and Xu Na, a Falun Gong practitioner and artist whose husband was killed in custody around the 2008 games, was sentenced to eight years in prison in early January for sharing information about the state of the pandemic in Beijing.

International pushback

The Chinese government can be expected to engage in some form of heightened information control during the Olympic Games, but it is less clear how international actors will respond. Will any athletes, perhaps after completing their competitions, publicly voice concerns about the plight of persecuted Uyghurs, Tibetans, Hong Kongers, Falun Gong practitioners, Chinese rights activists, or even a fellow athlete like Peng Shuai? Will international media outlets broadcasting the games limit their coverage to the sporting contest itself, or will they offer context on the political, social, and legal environment in which the games are taking place?

If the Chinese government and Beijing Organizing Committee blatantly violate terms of the contract they signed with the International Olympic Committee (IOC), such as its guarantees of media freedom and prohibitions on discrimination based on religion or political opinion, how will the committee react? Or if an athlete does speak out about rights violations in China, will corporate sponsors stand by them or cancel contracts for fear of a backlash from Beijing?

Fortunately, many news outlets have already referenced rights violations against Uyghurs and others in their pre-Olympic reporting, a growing list of governments have announced diplomatic boycotts, and tenacious activists worldwide are trying to raise even more awareness. In this sense the CCP has been less than successful in quashing debate and reporting on the darker side of its rule ahead of the games. In the true Olympic spirit of fairness and human dignity, one can only hope that this trend continues past February 4.

Sarah Cook is research director for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan at Freedom House and director of its China Media Bulletin. This article was also published in The Diplomat on January 26, 2022.