The 2009 carnage in Maguindanao, Philippines was an eye-opener not only for media people in the field but also for their desk-bound editors and publishers. Oftentimes taken for granted, journalist safety has become a concern and a priority.

This statement was originally published on seapa.org on 16 December 2014.

KIDAPAWAN, Philippines – Broadcast journalist Malu Manar resorted to wearing a headscarf and changed the way she dressed to elude gunmen who followed her around Cotabato city in 2004.

It was an election year and her reports displeased and angered a politician. She received death threats on her cell phone at first; then she was tailed by armed men in a white van.

“I knew they were after me because they knew my (whereabouts). When I went to church, I saw them there. I saw the same guys in the office,” recounts Manar, currently the head of news and current affairs of radio station DXND-NDBC.

She tried to outsmart the men who were out to intimidate, if not kill her. “I had to change how I dressed, except for my glasses. I cannot see without my glasses. I wore the hijab. I wore long clothes. My two kids, I also changed how they dressed,” she told reporters.

Realizing she could get killed, Manar’s office in Cotabato city shipped her off to their station in Kidapawan in North Cotabato, about 120 kms away and far from harm’s way.

Ten years on, the same pattern of threats and violence continues.

Many journalists, especially in the provinces, are facing the same threats that forced Manar’s family to relocate in 2004. Violence against journalists has not stopped and the perpetrators still get away scot-free, highlighting a climate of impunity that further emboldens people of influence and wealth to employ extra-legal means to silence critics and crusading journalists.

Their targets, meanwhile, have become bolder in their response to threats and assassination attempts, especially after the November 23, 2009 Maguindanao massacre that killed 58 people, including 32 media workers.

Previously, journalists would go into hiding until the situation cooled, or changed their looks to hide their identity like what Manar did to throw gunmen off her trail. These days, keeping safe could mean carrying a gun.

Aquiles Zonio, who already had a licensed handgun prior to the gruesome murders of his colleagues in 2009, says: “In this country, once you get a death threat, consider your entire life under threat.”

“Never ever lower your guard. That’s why I always watch my back,” adds the veteran reporter from the Philippine Daily Inquirer who has received death threats for his exposes on illegal mining and logging in southern provinces.

“Feeling safe does not mean you have to be complacent about it. You must always be security conscious. You always bear in mind security measures,” Joseph Jubelag, from the Mindanao Bulletin, explained to this reporter.

Zonio and Jubelag both escaped the massacre five years ago. They were originally part of the election convoy on its way to file the certificate of candidacy for governor of then Buluan vice-mayor Esmael Mangudadatu. They broke away from the group and intended to follow afterwards but their instincts got the better of them.

That change of heart saved their lives.

Safety training

Safety training among journalists assigned to cover war-torn countries like Iraq or Syria is standard procedure among journalists working for international news agencies or networks, but is hardly the norm in countries like the Philippines despite the security risks media personnel face in covering the country’s communist insurgency and Muslim rebellion.

The carnage in Maguindanao was an eye-opener not only for media people in the field but also for their desk-bound editors and publishers. Oftentimes taken for granted, journalist safety has become a concern and a priority.

With the continuing threats against journalists in the Philippines, some media companies have become conscious of the need to provide safety orientation or training for their correspondents in the provinces, or when sending out reporters on special assignments in conflict areas.

Jubelag, who also writes for the national broadsheet Manila Bulletin, says that whenever he has to go to a conflict area, he studies the ground situation before deciding whether to proceed or not. He also asks for information about the area from the locals and military authorities.

“Of course I have to be extra careful about my personal security because for us journalists, security is always a personal concern. You cannot leave your security to other people. You yourself must care for your safety,” adds the journalist who has undergone safety training.

John Unson, who writes for the Philippine Star, has also undergone some kind of training. He says the police and the military periodically give them lessons on security and safety, including life preservation techniques in hostile areas. They are also taught how to care for injured companions, and how to ensure their safety and wellness while being rushed to the hospital.

“Many of us have protective suits…Kevlar suits and helmets,” he explains. “We also always seek permission from the military. If they say ‘do not go there first until we have cleared the roads of landmines, until we have made sure there are no rebels’ then we will wait. The military have this practice of making the journalists wait until they have cleared the area of potential threats. They would not allow you to go to conflict areas while fighting is going on.”

Assessing security situations is also important, Unson points out. “We must know where to retreat or where to run to when caught in a cross-fire or in any hostile situation.” Asked what guidance they get from their editors, he says they offer caution to staff going into hostile areas.

“Sometimes they will even discourage you from going and tell you instead to gather information from sources via mobile phone. But you will always have this pumping of adrenaline and challenge to go into a hostile area.”

He warns: “So most important is prudence. You always have to decide wisely whether you need to go to a hostile area or not, when to pursue your coverage, when to stop your coverage, when to move out. That is prudence, wise judgment. And you always have to make a good judgment call.”

Victor Redmond Batario, the Southeast Asia Coordinator of the London-based International News Safety Institute, says the training they provide journalists working in hostile environments includes scenario-making and practical exercises that prepare the journalist for emergencies and situations like getting caught in a crossfire, dealing with hostile crowds or subjects, detecting and avoiding surveillance, behaving in checkpoints and general risk awareness.

But before embarking on any trip to conflict areas, he insists journalists and other media staff should prepare by finding out as much as they can about the place or area they are going to, the people they are likely to meet or interview (the cast of characters).

“Find out what the situation is. Is there a history of violence in the area? What are the political and social realities?” says Batario, a former journalist who also heads the Center for Community Journalism and Development.

Get as much practical information about the place, including the weather and the length of time the journalists will likely spend during the coverage, he adds. Such information will dictate the gear they will bring that should include food, water, communications equipment, and first aid kit.

Journalists or cowboys?

The impunity in the killing of media personnel made journalists aware of safety, but it also pushed the idea of carrying a gun an attractive option especially for those in the countryside, where the rule of law is weak and warlords with private militia call the shots.

While the thought of newsmen carrying guns was almost unheard of years ago, it is starting to become commonplace among newsmen these days, raising some questions within the media community.

It is hard to argue about guns with people who have narrowly escaped death, and who now feel that only a gun can provide them security. But not all are convinced it is the way to go.

Froilan Gallardo, a photojournalist at the Davao City-based Mindanews is opposed to arming journalists. “I do not carry a gun and I do not own one.” He adds: “I believe journalists who carry guns are simply cowards or acting out their childhood dreams of being cowboys.”

“I simply cannot see how anyone can work with a gun tucked on his waist or hidden in his bag.”

Argues Gallardo: “I doubt if the people you want to interview will trust you if they see you carrying a gun. Besides, many of the journalists who carried guns were not able to prevent their death. The gunmen were able to kill them despite the fact that they carried guns.”

Batario agrees carrying a gun is no guarantee. “I don’t believe that it provides any protection at all. At best, it provides a false sense of security. I know a number of journalists who were killed even while carrying firearms and even have armed bodyguards.”

Rowena Paraan, chairperson of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), agrees journalists are not well-suited to carry guns and doing so might be cause for injury rather than protection. “You are not a professional (at handling guns). You are not trained to shoot.”

“I have always discouraged the carrying of guns by journalists,” asserts Batario. “However, I will not stop a journalist from arming himself or herself if he or she feels that having a firearm will deter attacks especially if they have been receiving death threats,” he explains.

Carrying a gun is not an ethical issue, broadcast journalist Chino Gaston says in an interview in Manila. “It is a personal choice. I can choose to carry a gun in Metro Manila if I wanted to, just as journalists in the provinces can also carry guns … if they have come under threat.”

He adds: “It is a choice best left to that particular journalist and no one has the right to dictate or issue a set of rules saying it is ethical or not.”

A new law that came into effect in early 2014 allows journalists to carry their licensed guns outside the home. Republic Act 10591 identifies them, along with priests, lawyers, nurses, doctors, accountants and engineers as “in imminent danger due to the nature of their profession”.

Under the previous law, people in those sectors, like any other citizen, had to prove they were “under real threat” of danger before a gun could be issued to them.

The new law is not without its critics who say making guns more accessible could result in more violence. But supporters of the law argue that it allows civilians to defend themselves against threats.

According to Gaston, from the Manila-based GMA Network who goes on regular coverage to the provinces, the matter of guns for protection is different in the capital, compared to the countryside.

There are far fewer journalists in metro Manila who carry guns than in the provinces because they do not face the same threats their counterparts in the southern region do, he says. Reporters in the capital get intimidating text messages, seldom death threats, he adds.

“(Hired men) go as far as ransack your house to scare you, but very few death threats compared to those in the region,” explains Gaston who says better law enforcement in the Manila makes it relatively safer for journalists.

For Paraan, the pervasive gun culture in the provinces, where people grow up seeing guns, is what makes it relatively easier for journalists to arm themselves.

“If you go to places like Mindanao, it is very common, very natural for a local journalist, when he feels under threat, to carry that gun with him.”

Gun or no gun, Batario believes that a journalist’s best defence is responsible reporting.

“I have always emphasized that the best protection any journalist can ever have is the practice of responsible journalism which means adhering to the highest standards of the craft,” he explains. “Of course, it does not guarantee 100 percent protection but it does lessen the chances of a journalist being subjected to harassment or violence,” he adds.

Cycle of Impunity

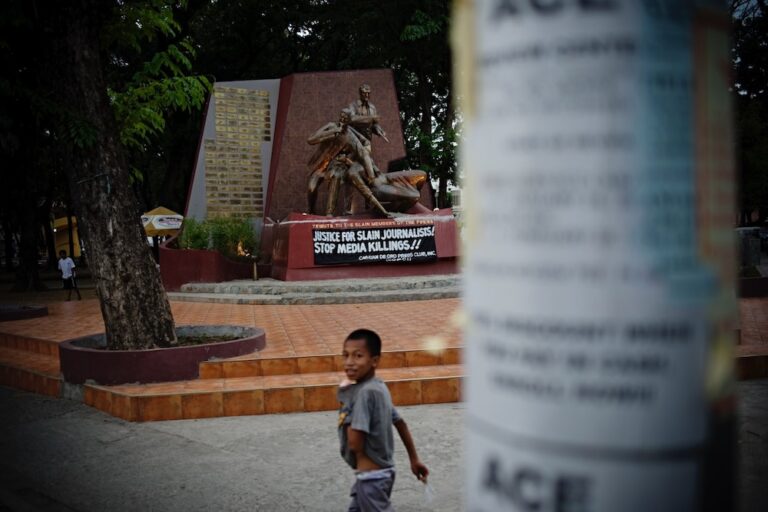

The cold-blooded killings in Maguindanao, which took the lives of innocent media workers, reinforced the country’s reputation as being unsafe for journalists. The Philippines is ranked third, after Iraq and Somalia, in the 2014 Global Impunity Index of the Committee to Project Journalists (CPJ).

More than 50 journalist murders from 2004 through 2013 remain unsolved, according to the New York-based media watchdog.

The Philippines’ Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility reports that more than 200 journalists have been murdered around the country since 1986, when democracy was restored, and only 14 cases have led to convictions. Only gunmen have faced justice, however, and no mastermind has ever been convicted, it says.

The unpunished crimes clearly have a chilling effect on journalists.

According to Zonio, perpetrators are not afraid to kill journalists because they know they can get away with it. On the other hand, after the Maguindanao massacre, some journalists in the region did not dare cover critical issues they would otherwise write about, he recalls.

Charlie Saceda of the Peace and Conflict Journalism Network explains: “When other journalists are being killed because they are uncovering corruption issues, other journalists will already think twice about reporting those issues.”

While impunity strikes fear in the hearts of journalists, it only serves to embolden the perpetrators.

“When wrongdoing goes unpunished it means those who commit it will have no compunction about repeating the wrongdoing,” Batario points out.

President Benigno Aquino has given assurances that killers of journalists will be prosecuted and sent to jail, but he himself admitted, in reply to a journalist’s question earlier this year that “speed is not a hallmark of our current judicial system.”

For NUJP’s Paraan, the reasons impunity persists are complex. “Power, definitely it is connected to power,” she told a group of journalists. “Impunity cannot exist if institutions work, if those who commit the crime are not tolerated by those in power.”

“If you have a government that is able to protect its citizens, then you go to the police and report (threats). That is the primary obligation of the government to its citizens,” she points out. “But because that doesn’t work here, you rely on yourself, on your colleagues to protect you.”

Paraan says provincial journalists are more vulnerable to attacks because the rule of law is weaker in the provinces than in the capital, Manila, and “whoever is in power is like a king”.

But she explains that it is not only media that is under attack, but also activists and other groups in society like lawyers and even priests fighting for human rights and greater freedom of expression. “One good thing that came out of the campaign to seek justice for the killing of journalists is it brought into focus the killings in other sectors.”

Lessons for Myanmar

Journalists in Myanmar face a different kind of threat compared to their counterparts in the Philippines. Those who write stories considered critical to the state or the military face imprisonment or fines.

In October, three journalists and two publishers of Bi Mon Te Nay were given two-year prison sentences by a court in Rangoon for defamation. Last month, the Ministry of Information sued 11 staff members of Myanmar Thandawsint under the new Media Law passed in April that imposes fines on offenders.

Meanwhile, four journalists and the chief executive officer of the independent Unity journal are serving a seven-year reduced prison sentence for violating the Official Secrets Act.

Also in October, the Army reported that freelance journalist Aung Kyaw Naing was killed “while attempting to escape” from his military captors in a case which human rights campaigners say indicate that the armed forces have changed little. They are calling for an investigation into his murder.

The military had ruled Burma with an iron first for five decades until it was replaced by a quasi-civilian government in 2011, but political reforms, including an easing of restrictions on the media, seem to have stalled.

The Southeast Asian Press Alliance describes the killing of the freelance journalist as a “test of the accountability of the military for such acts and the resolve of the government to protect journalists”.

“These recent alarming incidents this year … indicate that media freedoms in the country have been short-lived, and earlier praise heaped on the government for easing restrictions, is premature,” the Bangkok-based regional media watchdog said in a statement.

The arrest and murder of Aung Kyaw Naing, who was reporting on the conflict between the Burmese army and one of the country’s rebel ethnic groups, raised concerns over the safety of reporters going into conflict areas.

“There are safety concerns for Myanmar journalists especially in conflict reporting,” says Nyan Lynn, editor of Maw Kun Magazine. “They are not under such threats that Filipino journalists face, but they need to learn about safety training.”

An editor from Morden Weekly Journal, Ko San Yu Kyaw adds: “We don’t know how to protect ourselves. We need to learn and practice safety tips in our daily reporting. In Burma, after the so-called reform, we feel more insecure as we have more issues to cover and more challenges (to face).”

May Thingyan Hein, chief executive officer of Myit Makha News Agency, is concerned about the overall quality of journalistic reporting in the country. “Even though we think if we report ethically we will be safe, it is not like that in reality.”

She adds: “When we try to get news from the government side it is difficult so we try to get information in whatever way we can. But there are certain laws that might get us into trouble such as the electronic transaction act. The Official Secrets Act is also a threat to journalists in Myanmar.”

[This article was produced for the 2014 Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) fellowship program. Eaint Khine Oo is a Burmese Journalist, working as Contributor in Myanmar Media Review Program of the Voice of America (VOA) Burmese Section, Burma, is one of the 2014 fellows. This year’s theme is Promoting a regional understanding of impunity in journalists killing in the Philippines.]