The authorities in several Central Asian states have warned news outlets to tone down their coverage of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, or ignore it entirely.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 19 April 2022.

To avoid offending their Russian neighbour, the authorities in the five Central Asian republics are pressuring their media to provide “neutral” coverage of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or ignore it altogether. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) calls on these governments to allow journalists to cover the war and its consequences as they see fit.

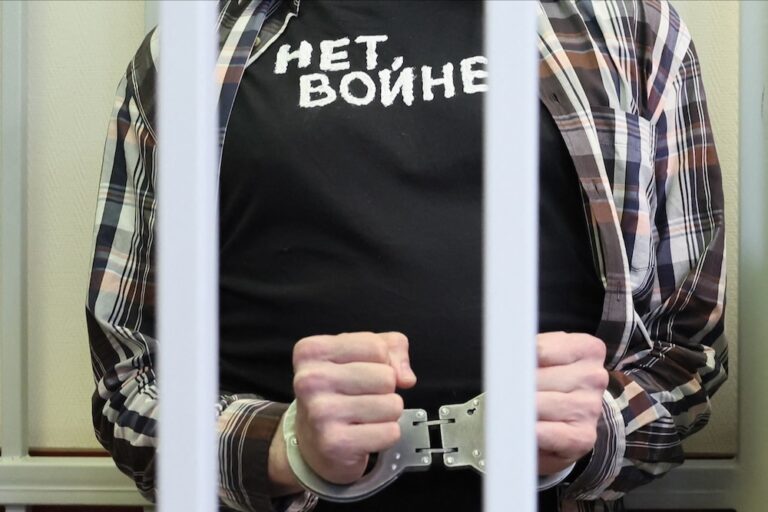

In Kyrgyzstan, Next TV director Taalai Duishenbiev is facing up to seven years in prison on charges of spreading false information and “inciting ethnic hatred” because of a report about the war in Ukraine that this opposition TV channel reposted on its social media accounts.

Duishenbiev was arrested, Next TV’s offices in the capital, Bishkek, were sealed and several employees were questioned after it reposted a report on 2 March in which the exiled former head of neighbouring Kazakhstan’s Committee for National Security (KNB) was quoted as referring to a supposed secret agreement between Bishkek and Moscow for Kyrgyzstan to provide military assistance to Russia in Ukraine. On 29 March, a court in Bishkek ruled that the post was “extremist.”

In Uzbekistan, the authorities have been trying to intimidate journalists and bloggers into toning down their coverage of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and some articles on the subject on the popular news sites Kun.uz and Daryo.uz were later deleted. Kun.uz editor Umid Shermukhammedov and two of the site’s founders were summoned for questioning by the National Security Service (SNB) on 26 February, according to a (later-deleted) post on its Facebook account. The editor was reportedly ordered to cover the subject in a more “neutral” way.

Rost24 news website editor Anora Sodikova told Radio Ozodlik (the Uzbek service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty) that several of her colleagues have been subjected to similar pressure. Meanwhile, as in Russia, the Uzbek state media avoid using the words “invasion” or “aggression.”

“The media should not be getting instructions from the security forces on how to cover events,” said the head of RSF’s Eastern Europe and Central Asia desk. “We call on the authorities in Central Asian countries to stop pressuring journalists in this way and to respect the independence of the press.”

In Kazakhstan, the word “war” is not banned but the coverage provided by state media and media owned by leading businessmen is very cautious, and pressure is being put on the independent weekly Uralskaya Nedelya. One of its main advertisers has withdrawn its advertisements, accusing it of taking an “anti-Russian” line because a post on its Instagram account explained how to help Ukrainian volunteers collect medicine for the Ukrainian army and the people of Kyiv. Its Instagram account was also attacked by Russian bots at the start of the war, editor Tamara Eslyamova said.

In Tajikistan, the few independent media outlets cover the war but it is ignored by state-controlled television. The security services told TV channel executives to refrain from covering it, according to CABAR.asia. In Turkmenistan, which is one of the world’s most closed countries and where all media are controlled by the state, the state news agency TDH has not mentioned the war.

Kyrgyzstan is ranked 79th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2021 World Press Freedom Index, Kazakhstan is 155th, Uzbekistan is ranked 157th, Tajikistan is 162nd and Turkmenistan is 178th.