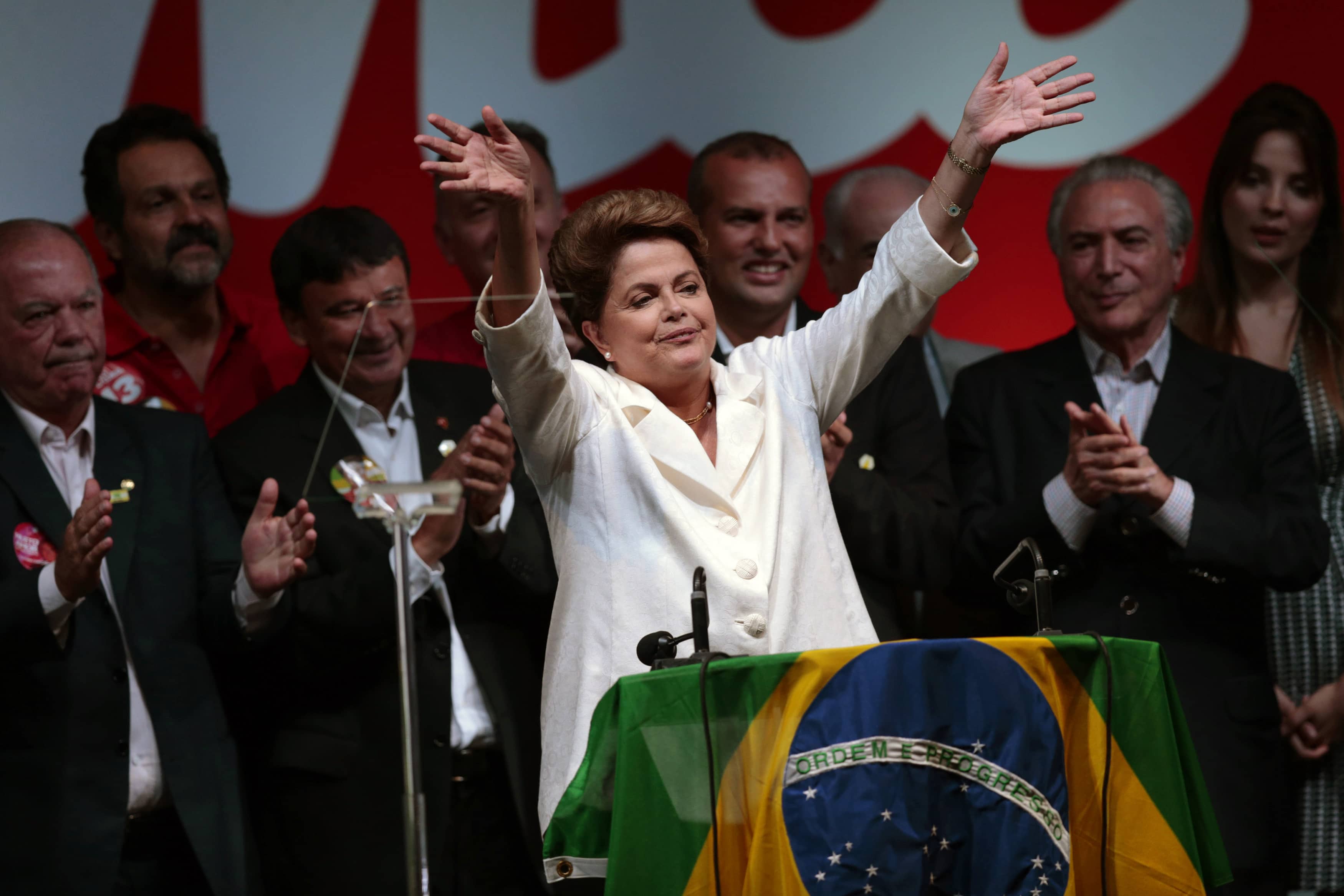

Dilma Rousseff was reelected on 26 October, winning a fourth consecutive term for the Workers’ Party. Reporters Without Borders is taking this opportunity to highlight two major challenges facing the government – journalists’ safety and a skewed media landscape.

This article was originally published on rsf.org on 5 November 2014.

Freedom of information has made important progress in Brazil during the past 12 years under President Lula da Silva and (since 2011) his successor Dilma Rousseff, who was reelected on 26 October, winning a fourth consecutive term for the Workers’ Party (PT), but much remains to be done. Reporters Without Borders takes this opportunity to highlight the two major challenges facing the government in the years ahead as regards freedom of information – journalists’ safety and a skewed media landscape.

The past decade’s progress includes repeal of the 1967 press law in 2009 (a law inherited from the military dictatorship under which journalists could be jailed for “subversive” reporting), suspension of a clause in the 1967 electoral law banning cartoons during election campaigns, and a law on access to information that took effect in 2012.

This year saw further progress when Brazil passed an “Internet Civil Framework” law in April. The only one of its kind, this law guarantees protection of privacy and freedom of expression for Internet users, putting Brazil in the forefront of the protection of online civil rights.

One of the region’s deadliest countries for journalists

Despite the progress, the past few years have also seen many violations of freedom of information. Brazil has experienced a sharp rise in physical attacks on journalists and bloggers and is now one of the deadliest countries for media personnel in the Americas.

A total of 38 journalists have been killed since 2000 in clear or probable connection with their work. Most were covering sensitive stories such as drug trafficking, corruption or local political disputes. No fewer than 11 journalists were killed in 2012, at least five of them in direct connection with their work. The figures for 2013 and 2014 are also high.

Reporters Without Borders was consulted in the drafting of a report on violence against journalists that Brazil’s Human Rights Secretariat (SDH) issued in March, a month after Bandeirantes TV cameraman Santiago Ilídio Andrade was killed during a protest in Rio de Janeiro.

Noting that at least 321 journalists have been the victims of violence from 2009 to 2014, the report said local authorities were often involved in the attacks on journalists and it highlighted impunity as a factor in their constant recurrence.

The recommendation by the working group in charge of the report included creating an Observatory for Violence against Journalists in partnership with the United Nations as an extension of the current mechanism for protecting the human rights of journalists and bloggers.

The working group also recommended putting the federal authorities in charge of investigating crimes against journalists (because local authorities often show little interest in investigating them), a justice ministry evaluation of suitable security equipment for protecting journalists covering conflicts, and new police methods during demonstrations.

On this last point, the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalists reported that there were 190 attacks on journalists during the many demonstrations from May 2013 to July 2014, and that the military police were responsible for more than 80 percent of these attacks.

Despite the scale of these abuses, a São Paulo court refused on 5 September 2014 to compensate photographer Alex Silveira for losing his sight in one eye, after he was hit by a rubber bullet fired by a policeman while Silveira was covering a demonstration in São Paulo in 2003. The “only person responsible for this lamentable incident was the victim,” the court ruled.

This decision sets a dangerous precedent with regard to police behaviour towards journalists and clearly violates the principles of the resolution on the promotion and protection of human rights during protests that the UN Human Rights Council adopted on 28 March.

This resolution calls on governments “to pay particular attention to the safety of journalists and media workers covering peaceful protests, taking into account their specific role, exposure and vulnerability.”

Ownership by the few limits media pluralism

The concentration of media ownership in very few hands is another factor undermining freedom of information. Ten leading business groups owned by as many families dominate the mass media market and broadcast frequencies.

Media pluralism is also affected by the way the state allocates its massive advertising budget, which favours the leading media groups and results in a degree of financial dependency and extremely close relations between media, private sector and politicians.

Concentrated ownership together with pressure and censorship at the local level are the defining features of a media system that has never been really questioned since the end of the 1964-85 military dictatorship, a system in which community broadcast media are among the main victims.

Half a century after its adoption, the 1962 telecommunications law has never been thoroughly overhauled and continues to regulate broadcast frequencies. Article 220 of the 1988 federal constitution bans monopolies and oligopolies in the media and communications sectors but the National Congress has never defined these terms or enacted a law specifically limiting ownership within or across media sectors.

Brazil’s progressively-minded community broadcast networks regard the new legislation in neighbouring countries such as Argentina, Ecuador and Uruguay with envy and find it hard to accept the lack of progress under the Workers’ Party administrations, which have not dared to meddle with regulatory legislation.

Communications minister Franklin Martins tried to take a step forward by bringing representatives of government, civil society and privately-owned media together for the first national conference on communications (CONFECOM) in Brasilia in 2009. New media legislation was discussed but no agreement was reached and no proposals were ever published.

The challenge is complicated by the fact that the dominant media energetically reject any proposed regulation or democratization of the broadcast media, always accusing the government of wanting to restrict freedom of expression.

Another factor complicating a thorough reform of the communications sector is the large number of politicians who own radio and TV stations. According to a survey by the Donos da Midia project, 271 elected politicians owned or were partners in 324 news media in 2009.

During a visit to Brazil in 2013, Frank La Rue, then UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, called for better media regulation and said media ownership by

the few led to political control by the few, posing a major obstacle to pluralism.

Reporters Without Borders’ recommendations

To reduce the extreme frequency of physical attacks and murders targeting journalists and to satisfy the calls by both journalists and civil society for more media pluralism in Brazil, Reporters Without Borders advocates:

– The rapid implementation of the recommendations by the Human Rights Secretariat’s working group on the safety of journalists, in order to create a mechanism that gives them effective protection. RWB also endorses the working group’s proposed creation of an Observatory for Violence against Journalists in partnership with the United Nations.

– Respect for the principles of the UN Human Rights Council’s 28 March resolution on the promotion and protection of human rights during protests. Brazil must establish police behaviour codes that guarantee the safety of journalists during demonstrations.

– A thorough overhaul of the current media regulatory legislation, which is no longer appropriate. The new laws must include strict rules on media ownership and media funding via state advertising.

– The inclusion in this future legislation of provisions on the allocation of broadcast frequencies that make room for community broadcasters, until now under-represented in the field of legal frequencies. Broadcast licence allocation should be transparent and should involve civil society in order to guarantee parity between community, state-owned and commercial media. The recently adopted legislation in Argentina and Uruguay could serve as examples for Brazil’s legislators.