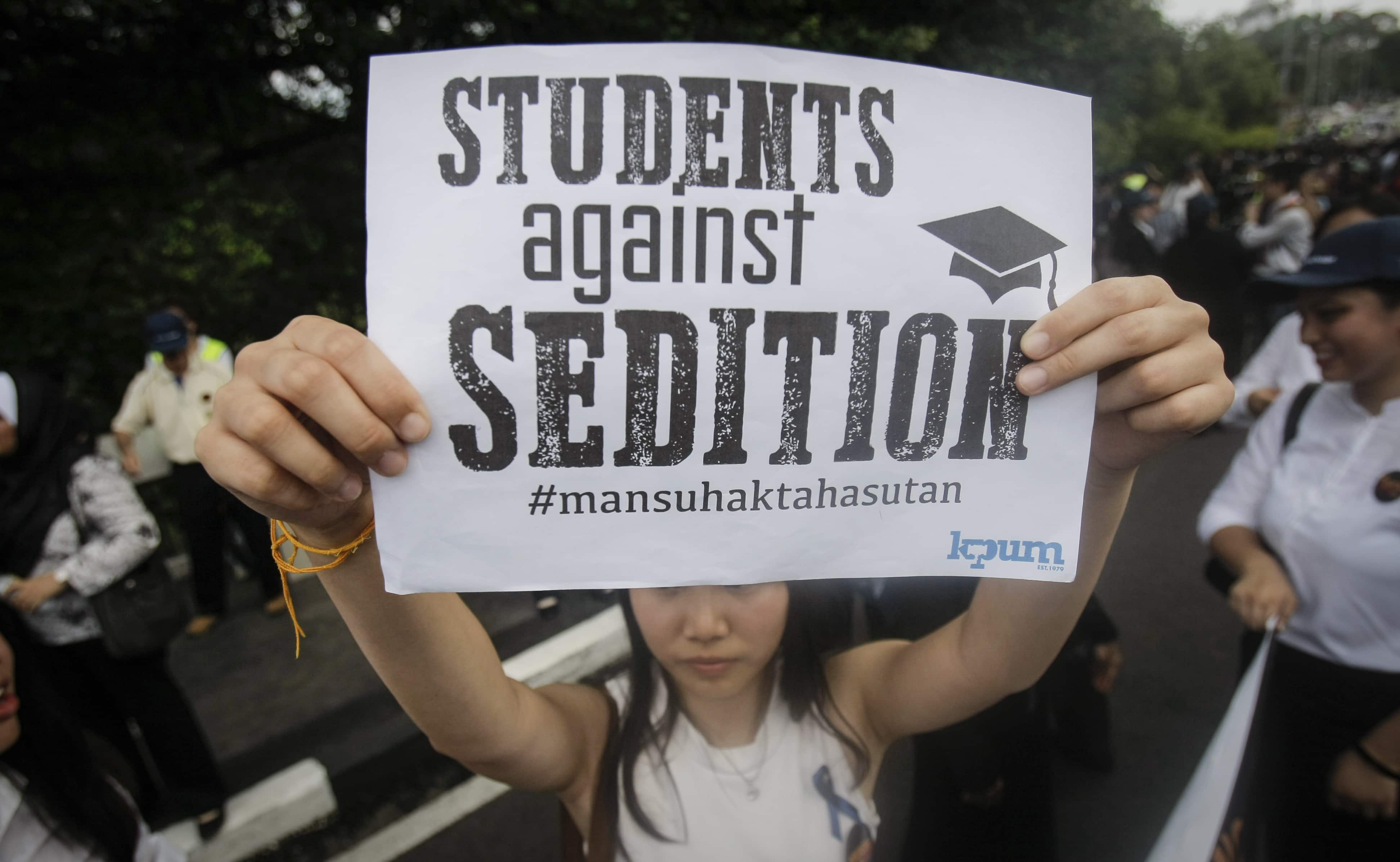

ARTICLE 19 is disappointed by Malaysia's Federal Court decision that the colonial era Sedition Act is indeed constitutional. This is the second recent court decision which brings into question the judiciary's ability to safeguard fundamental human rights, after the Court of Appeal found last week the criminalisation of peaceful assemblies to be constitutional.

This statement was originally published on article19.org on 6 October 2015.

ARTICLE 19 is disappointed by Malaysia’s 6 October 2015 Federal Court decision that the colonial era Sedition Act is indeed constitutional.

The Sedition Act violates international human rights law on freedom of expression and contradicts democratic values. ARTICLE 19 urges its repeal.

“The 1948 Sedition Act has been increasingly used to suppress legitimate offline and online dissent in Malaysia, whether by academics, cartoonists or opposition politicians. Many of those brave individuals who have spoken out against the government already have sedition charges against them, and were awaiting the outcome of this decision. They now each face as many as 43 years in prison or significant fines,” said Thomas Hughes, Executive Director of ARTICLE 19.

This is the second recent court decision in Malaysia which brings into question the judiciary’s ability to safeguard fundamental human rights, after the Court of Appeal found last week the criminalisation of peaceful assemblies to be constitutional.

“It is profoundly disappointing to see these decisions, in a country already facing an increasing crackdown on free speech,” added Hughes.

On 6 October 2015, Malaysia’s apex Federal Court ruled that the 1948 Sedition Act is constitutional. The legal challenge was brought by Professor Azmi Sharom, who is facing a criminal prosecution for comments he made in an interview to the Malay Mail Online regarding a political crisis in the state of Selangor.

The Sedition Act 1948, a relic of British colonial rule, criminalises any conduct with a “seditious tendency”, including a tendency to “excite disaffection” against or “bring into hatred or contempt” the ruler or government. It does not require the prosecution to prove intent, and provides for up to three years imprisonment and/or a fine of 5000 Ringgit for those found guilty of a first offence. Subsequent offences may be punished with up to five years imprisonment.

The Federal Court ruled that the 1948 Sedition Act was compatible with Article 10 of Malaysia’s Federal Constitution, which guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression. Its ruling focuses in part on Article 10(2)(a) of the Federal Constitution, which permits Parliament by law to impose restrictions on the right to freedom of expression “as it deems necessary or expedient in the interest of the security of the Federation.”

The Federal Court determined that the assessment of what is “necessary or expedient” in balancing fundamental rights with security interests lies with Parliament, and not with the Courts. In so doing, the decision hands significant deference to a legislature which has recently expanded the government’s powers to crack down on freedom of expression, at the same time considerably limiting the Court’s own oversight role in safeguarding fundamental rights.

The Federal Court’s decision means that Professor Azmi Sharom’s case will be remitted to Sessions court, where he will be tried for “sedition”, and if found guilty face a fine or likely prison term. A host of other sedition trials that were postponed pending the outcome of the Federal Court decision will now likely go ahead, including that of cartoonist Zunar, who faces up to 43 years in prison for 9 counts of sedition over a single tweet, and human rights lawyer Eric Paulsen.

ARTICLE 19 finds that the Federal Court’s ruling on the compatibility of the 1948 Sedition Act with Malaysia’s constitution contradicts international standards on the right to freedom of expression:

– It is ambiguous and unclear, and therefore not prescribed by law; it grants authorities too much discretion for arbitrary enforcement and therefore its scope is unforeseeable;

– It does not pursue a legitimate aim, abusing the framework of “national security” to clamp down on dissent which poses no genuine threat to a legitimate national security interest;

– It is not necessary in a democratic society, as States must protect and promote robust debate on matters in the public interest. There is no evidence that Azmi Sharom’s allegedly “seditious” comments intended to incite violence or that they were likely to do so. Malaysia’s constitutional safeguards fall short of international standards by allowing restrictions on expression where they are merely expedient to the government, rather than necessary in a democratic society.

Importantly, in General Comment No. 34 the UN Human Rights Committee made it clear that expression critical of the government should not be subject to penalties.

The use of the Sedition Act to suppress dissent in Malaysia has received significant criticism from the UN, including by a host of UN Human Rights Council special procedures, including the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression.

Addressing the UN Human Rights Council at its 30th Session on 14 September 2015, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, expressed dismay at the Malaysian government’s recent amendments to the 1948 Sedition Act, which broaden categories of offences and increase penalties. These amendments, though approved by Parliament, will only come into effect when officially gazetted, which is expected in the coming weeks.

As of April 2015, at least 78 people had been investigated or charged under the Sedition Act since the beginning of 2014, representing a significant escalation in Malaysia’s crackdown on critical voices. 7 individuals have been convicted for sedition since mid-2013. In recent months, the government has employed a variety of other laws besides the Sedition Act to target independent media, and block websites to frustrate the exercise of protest rights.

On 1 October 2015, Malaysia’s Court of Appeal issued a decision in the case of Yuneswaran, finding constitutional a criminal conviction for organizing a peaceful assembly without complying with a 10-day prior-notification requirement set out in section 9(5) of the Peaceful Assembly Act 2012. The decision has been heavily criticized for departing from a prior Court of Appeal precedent in the Nik Nazmi case, which found the 10-day notification requirement to be unconstitutional. Taken together with the Federal Court’s 6 October decision on the Sedition Act, the credibility of Malaysia’s judiciary as a guardian of fundamental rights has been severely jeopardized.

Malaysia has not signed or ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the primary international human rights instrument that guarantees the right to freedom of expression in article 19. The covenant has 168 States parties, making Malaysia an outlier in its international commitments to protect and promote human rights.

The international community must urge Prime Minister Najib to fulfill his 2012 promise to repeal the Sedition Act without delay, and demonstrate his government’s commitment to protecting fundamental freedoms by dropping all charges, committing to reform the 2012 Peaceful Assembly Act and other restrictive laws, and by ratifying the ICCPR.