National elections were held in six countries in Southeast Asia in the past year, with more to come. These interesting times are particularly challenging for the media in maintaining its documentation role as citizens exercise their right to directly participate in politics.

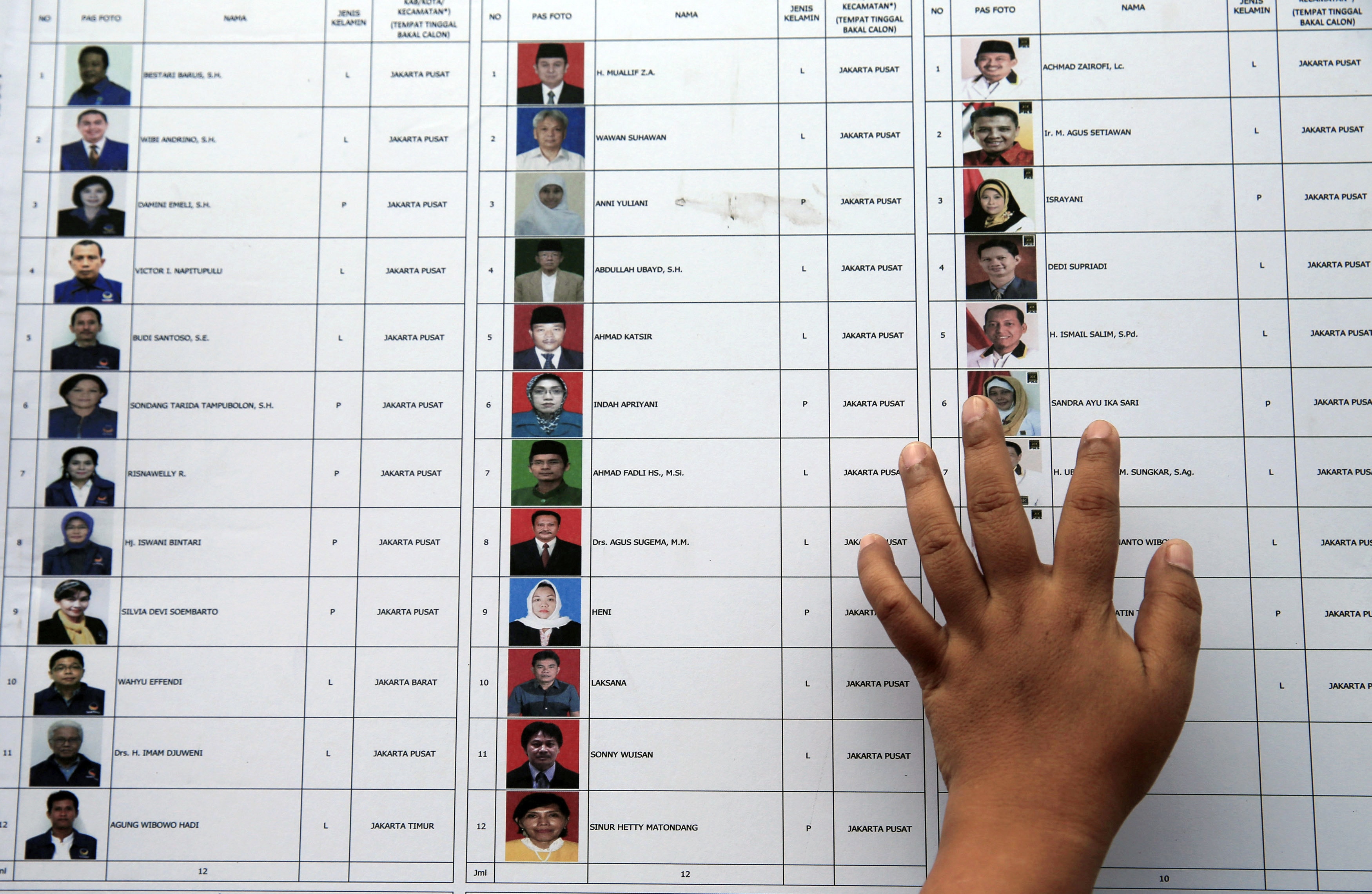

National elections provide a common context of key developments in the media freedom situation in six countries in Southeast Asia countries this year. In 2013 and early 2014, elections were held in Cambodia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. There is also great anticipation of the forthcoming presidential elections in Indonesia later in 2014 (after parliamentary elections in early April) and, of course, in Burma next year. Relatedly, Timor Leste politics also enters an interesting phase with the announced retirement of Prime Minister and former resistance leader Xanana Gusmao in September.

These interesting times (to say the least) are particularly challenging for the media in maintaining its role to document a nation’s unfolding history as citizens exercise their right to directly participate in politics. As for the rest of Southeast Asia, political exercises are largely one-sided in Laos and Vietnam, are not held at all in Brunei (not covered in our reports), and were held in Singapore in 2011.

Journalists participating in SEAPA-conducted workshops on “Elections and the Media” in Jakarta (February 2014) and Phnom Penh (July 2013) echo the challenges faced by the media in elections where the added pressure of raised political stakes also increase the challenge of independence, safety risks, and ethical issues of the profession. Journalistic skills are also put to the test, raising the need for more training on election coverage.

The internal workings of the media industry also face scrutiny during poll season as media ownership (in Cambodia and Indonesia) and revenue from political advertising comes into question. While elections normally flood citizens with unprecedented amounts of political information from campaigns, the question should still be raised on whether voters are getting relevant information to make informed choices. Political propaganda dominates electoral discourses, instead of a sober accounting of the track records and conduct of politicians and parties.

In some cases, elections bring about tensions that resulted in threats and attacks against journalists. In Cambodia, the tainted victory of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party in the July 2013 elections resulted in an extended political crisis, after the opposition refused to take their palrliamentary seats. Journalists and activists were injured when some protests of the opposition and civil society broken up by authorities. In Thailand, the political allegiances of media channels and workers has been severely tested by the political crisis that involved a failed parliamentary elections in February 2014. Protesters picketed government-owned TV channels in an attempt to sway media coverage away from government control, while some broadcast journalists in these channels have been threatened and attacked during their coverage of the protests.

Meanwhile, with 14 journalists killed – and 10 confirmed as work-related – in 2013, the Philippines saw the second highest annual count of media killings since 1986, next to the 2009 Ampatuan Massacre in Maguindanao. While none of these murders appear to be election-related, the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility has recorded 25 out of 68 incidents of attacks and threats against the media related to the mid-term elections for local government officials and Congress.

Beyond the role and challenges during elections, there is a concrete stake for the media in the political contests with the chances of improvement or restriction of press freedom and related issues changing between contesting parties or politicians. After all, it is government’s role to enact any law that will regulate or protect the journalism or use and access to media.

Media Laws

Burma began to move away from infamous draconian laws that kept media under control since 1962. Beginning with the abolition of pre-publication censorship, new media laws have been enacted in March 2014 to oversee different media, with the Press Law being perhaps the most important departure from the old regulatory regime.

The freer media environment stands among the most important indicators of democratization prior to the 2015 elections, although the relative freedom being experienced is mainly due to non-implementation of repressive laws that remain in place. In fact, the recently-enacted Press Law did not totally abolish the 1962 law but only repealed specific provisions that are conflict with the new law. More importantly, the government retained critical licensing powers over print media in the Printing and Publishing Registration Law.

In Timor Leste, the new press law seems to be finally moving toward enactment six years since the initiative was restarted to detail the constitutional provision guaranteeing press freedom and freedom of expression.

Elsewhere, Southeast Asian governments are falling in line to put regulations over online media and expression. Singapore received plenty of criticism for its sudden introduction of class licensing regulation for popular online news media, which falls outside the scope of existing regulations.

After more than a year since suspending the implementation of the Cybercrime Prevention Act, the Philippines’ Supreme Court finally ruled on the constitutionality of the law. The court struck down several provisions including those allowing government to block websites and collect metadata. However, free expression and media advocates criticised the court for finding as constitutional the crime of online libel.

These two key developments continue the regional trend to impose stricter regulations on online media and expression. Two countries – Cambodia and Laos – which have yet to enact such measures have also announced plans to introduce cyber-regulation laws.

Directions

Overall, the media situation in Southeast Asia remains largely where it is: countries with relatively freer media remain beset with the problems of impunity for violence and politics-related control through threats and lawsuits.

On the other hand, those with restricted media environments remain unchanged as their politics. There may be little overt censorship reported because control has been institutionalised through self-censorship by media houses or individual journalists who do not wish to risk their professions, safety or freedom.

In a way, the situation in Burma is emblematic of the stark choices faced by media in the region. From a tightly suppressed environment regulated by repressive laws, it has moved to relative freedom tackling previously prohibited topics. In this transition, censorship has been replaced with attacks, threats and lawsuits. Journalists are still jailed but now under defamation, security and even trespassing or obstruction laws.

Just as in Burma, the best hope for change lies in how journalists and civil society assert press freedom, and address perceived government excesses through self-regulation. Myamnar journalist groups have proven to be an effective advocacy platform for press freedom, at times flexing their new-found muscles as organized groups to take to the streets and resist the return to state regulation.

In Vietnam, too, bloggers are getting organized, and engaging in people’s diplomacy to convert international concern to concrete forms of support to help expand the space for self-expression. Notable example to emerge in 2013 are the Vietnamese Women for Human Rights (a network of bloggers who were victims of state suppression) and Statement 258 (to call attention to the penal code provision most-used to arrest bloggers).

However, hopes of regional level advocacy are still dim because of the absence of official channels for engagement in ASEAN, and even basic information on which body has the mandate to address which issue. Unless there is a decisive shift towards transparency and to open up channels for civil society to engage the regional group, ASEAN will remain out of reach and irrelevant to its peoples even as the regional community is set to be launched at the end of this year.

ASEAN’s potential as a regional platform to address free expression has also been effectively paralyzed by insitutionalizing the primacy of laws and çultures of member states in its bill of rights, and also by omitting the phrase “beyond/across borders” in its adoption of the right to freedom of opinion and expression.