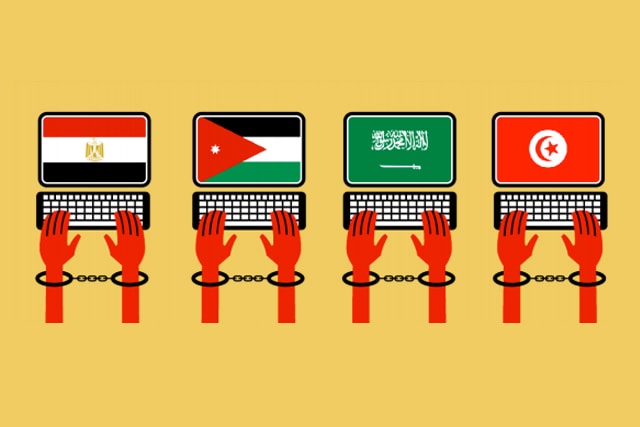

A study of four countries in the Arab world: Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia. Each has faced an increased threat of terrorist activity in recent years, and to varying degrees, each has responded by cracking down on online speech.

This statement was originally published on eff.org on 28 April 2016.

Freedom of expression is a universal right, but the specific threats to it vary widely from country to country and region to region. As activists fighting for free speech worldwide, it is essential that we better understand the specific legal and procedural mechanisms that governments use to silence it. When you begin to untangle the array of laws that are used to prosecute speech in a given country, you get a much clearer picture of the state of digital rights in that country.

EFF is proud to present The Crime of Speech: How Arab Governments Use the Law to Silence Expression Online. This report was the culmination of six months of work by Wafa Ben Hassine as an Information Controls Fellow through the Open Technology Fund. The ICFP fellowship supports examination into how governments restrict the free flow of information, debilitate the open Internet, and thereby threaten human rights and democracy.

Ben Hassine studied four specific countries in the Arab world: Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia. Each of those countries has faced an increased threat of terrorist activity in recent years, and to varying degrees, they’ve each responded by cracking down on certain kinds of online speech.

In Saudi Arabia and Jordan, that crackdown has come in the form of new cybercrime and counterterrorism laws that ultimately amount to banning online speech that the government finds threatening to its legitimacy. Today, Egypt primarily uses a 2014 anti-protest law to silence dissent online, while Tunisia targets online speech with decades-old defamation and drug laws found in the penal code.

To execute her research, Ben Hassine started by finding specific cases of arrest, detention, and imprisonment due to online activity, and where law enforcement targeted the individual under the guise of going after cybercrime or countering terrorism online.

The legal usage of the terms “cybercrime” and “terrorism” in countries such as Saudi Arabia and Jordan might be surprising to some readers. These laws do little to address the very real threat of online crime in their respective countries—Ben Hassine couldn’t find a single example of law enforcement using them to arrest criminals for attempting to break into critical infrastructure or engage in fraud online. Rather, the laws are aimed directly at unwanted online speech.

Studying the judicial history of these laws, you quickly realize that law enforcement only applies them after it’s identified the journalist or protestor that it wants to arrest. The pattern is that authorities will find the offending speech and then choose the law that can be interpreted to most closely address it. The system results in a rule by law rather than rule of law: the goal is to arrest, try, and punish the individual—the law is merely a tool used to reach an already predetermined conviction.

We hope that this report will serve as a useful building block for activists, scholars, and others studying digital rights and counterterrorism in the Arab world.