The 37-page report, "Rights in Retreat: Abuses in Crimea" and accompanying video document the intimidation and harassment of Crimea residents who oppose Russia's actions in Crimea, in particular Crimean Tatars, as well as activists and journalists.

This statement was originally published on hrw.org on 17 November 2014.

Russian and local authorities have severely curtailed human rights protections in Crimea since Russia began its occupation of the peninsula in February 2014, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The report, based on recent, on-the-ground research in Crimea, describes the human rights consequences of the extension of Russian law and policy to Crimea since the occupation. Russia has violated multiple obligations it has as an occupying power under international humanitarian law – in particular in relation to the protection of civilians’ rights, Human Rights Watch found.

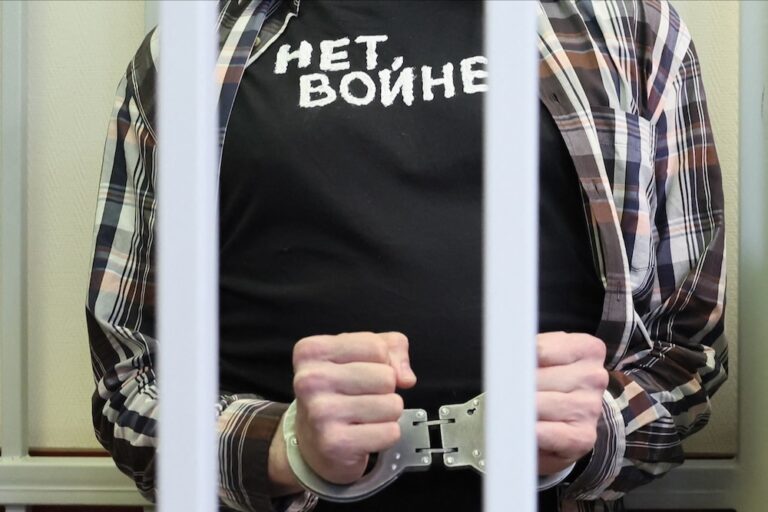

The 37-page report, “Rights in Retreat: Abuses in Crimea,” and accompanying video document the intimidation and harassment of Crimea residents who oppose Russia’s actions in Crimea, in particular Crimean Tatars, as well as activists and journalists. The authorities have failed to rein in abuses by paramilitary groups implicated in serious human rights abuses, including enforced disappearances of pro-Ukrainian activists and others perceived as critical of Russia. The authorities have compelled Crimea residents who were Ukrainian citizens either to become Russian citizens or, if they reject Russian citizenship, to be deemed foreigners in Crimea, removing any guarantee against any future potential expulsion.

“As the world’s attention has been on the hostilities in eastern Ukraine, rights abuses in Crimea have surged,” said Yulia Gorbunova, Europe and Central Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Under various pretexts, such as combating extremism, the authorities have been persecuting people who dared to openly voice criticism of Russia’s actions on the peninsula.”

The report is based on 42 interviews with members of the Crimean Tatar community, activists, journalists, lawyers, and others, which took place in Crimea, Kiev, Lviv, and Moscow. On November 6, Human Rights Watch sent letters summarizing key findings and concerns to the de facto authorities in Crimea.

Other countries and international organizations should not let the human rights decline in Crimea fall off their agenda, Human Rights Watch said. They should press members of the United Nations Security Council to adopt a resolution urging the full implementation of recommendations regarding the situation in Crimea contained in reports on Ukraine by the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine. They should also press for immediate and unfettered access to Crimea for relevant human rights mechanisms of the UN, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the Council of Europe, as well as access for the OSCE’s Special Monitoring Mission to establish a permanent presence in Crimea to operate and report freely.

Russia and the de facto authorities in Crimea should allow access for human rights monitors from these bodies to monitor human rights in the territory.

Russia, together with the authorities in Crimea, has invoked Russia’s vaguely worded and overly broad anti-extremism legislation to issue multiple “anti-extremist warnings” to the Mejlis, the Crimean Tatar representative body, Human Rights Watch said. Such warnings can be the precursor to shutting down the organization as well as to potential criminal prosecution against its individual members. The authorities have searched dozens of private homes of Crimean Tatars and conducted invasive, and in some cases unwarranted, searches of mosques and Islamic schools to look for “drugs, weapons, and prohibited literature.”

In accordance with Russia’s position of applying its federal laws in Crimea, Russia has set a January 2015 deadline by which media outlets in Crimea must re-register under Russian law. Local authorities have harassed pro-Ukraine and Crimean Tatar media outlets, searched their offices, shut some down, and threatened others with closure. Russia’s Federal Security Service and the Crimea prosecutor’s office have issued warnings to leading Crimean Tatar media outlets not to publish “extremist materials” and threatened editors that the outlets will not be allowed to re-register unless they change their “anti-Russian” editorial line.

Crimean residents who wish to remain Ukrainian citizens are now treated as foreigners in their own home territory, Human Rights Watch said. They had only one month to decide whether to take Russian citizenship or face adverse consequences. Those who wanted to retain their Ukrainian citizenship faced substantial barriers to completing the process, and the process of obtaining permanent residence status was not automatic.

As Ukrainian nationals, they will be barred from holding government and municipal jobs and treated as foreign migrants in their own country. Men of conscription age who acquired Russian citizenship, whether through choice or default, will be subject to Russian mandatory military service requirements.

“Russia is not really offering people a choice of citizenship but forcing civilians under its control to choose between taking Russian citizenship or facing discrimination and worse,” Gorbunova said. “This is a serious violation of international law and is in reality no choice at all.”

Under the 1949 Geneva Conventions, territory is considered “occupied” when it comes under the control or authority of foreign armed forces, whether partially or entirely, without the consent of the domestic government. This is a factual determination, and the reasons or motives that lead to the occupation or are the basis for continued occupation are irrelevant. Russia’s presence and effective control over Crimea, in the face of Ukrainian opposition and objection, constitutes a belligerent occupation, and the UN recognizes Crimea as part of Ukraine.

In keeping with its longstanding policy on laws of armed conflict, Human Rights Watch remains neutral on the military occupation of another country and therefore does not take a position on Russia’s occupation of Crimea. However, Human Rights Watch seeks to ensure that international laws governing the conduct of war and occupation are respected.

Under applicable international humanitarian law, an occupying power is forbidden from seeking to make a permanent change to the demographics of the occupied territory and from compelling the inhabitants of an occupied territory to swear allegiance to the occupying power or to serve in its armed or auxiliary forces, as well as from engaging in any “pressure or propaganda which aims at securing voluntary enlistment.” The occupying power has to maintain the laws in force in the territory at the time of occupation and cannot modify, suspend, or replace them with its own legislation unless it is absolutely prevented from doing so.

Russia is an occupying power as it exercises effective control in Crimea without the consent of the government of Ukraine, and there has been no legally recognized transfer of sovereignty to Russia.

“There has been a broad international outcry about Crimea,” Gorbunova said. “But it hasn’t been enough to stop abuses. More needs to be done, and the world needs to keep a very close eye on what is happening in Crimea.”