February 2023 in Africa: A special feature looks at a new African soft policy framework that considers the root causes of digital violence, plus the latest free expression news from the region, produced by IFEX's Regional Editor Reyhana Masters.

First of its kind: Resolution 522 aims to provide African women with new tool in fighting online violence

Whether private individuals or rising stars like Kenyan Elsa Majimbo, African women are often targeted with online violence. Could Resolution 522, recently adopted by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), push States to address these issues?

Crisp-crunching Kenyan Elsa Majimbo is a comedic sensation. The relatable monologues she began posting during the pandemic lockdown saw her social media presence balloon from 10,000 to 4 million followers.

In an interview with the New Yorker ahead of the launch of Elsa, a documentary charting her rise, Majimbo describes why she shares her opinions and quirky observations in the digital sphere. “I felt online I could fully be myself, . . . cause I was in my own space. It was just me. If people were coming, they were coming into my space. I wasn’t going into anyone’s space, so I never had to compromise for anyone.”

Therein lies the magic of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Tiktok, WhatsApp and so many social media platforms: they offer a path of freedom for people – especially women – looking to share their voice and exercise agency. But there’s a disturbing drawback to this liberating experience. The same emancipating space which allowed Majimbo to share her thoughts and experiences far beyond the confines of her family home in Nairobi, is also where she experienced backlash, cyberbullying and hate speech.

“Just speaking out – regardless of being a private individual or public figure – about certain issues online, . . . may be a trigger for violence and abuse,” explains the Commissioner for Human Rights for the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly, Dunja Mijatović.

“There seems to be a backlash on women online and those perpetrating this violence are operating quite freely.”Karen Mukwasi, director of The Pada Platform

And when it comes to online abuse, gender makes a difference. Women and gender nonconforming people are more likely to experience trolling, sexual violence, and body shaming while men tend to experience hate speech and satirical comments. According to Karen Mukwasi, director of The Pada Platform, “the online space is currently so toxic with blatant misogyny and underlying tones of violence against women. There seems to be a backlash on women online and those perpetrating this violence are operating quite freely. Leaking intimate images and hate speech seem to be celebrated as a way of finally putting those women firmly back in their place.”

But a resolution recently adopted by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) could help push member states to address these issues. Resolution 522 on the Protection of Women Against Digital Violence in Africa, adopted by the (ACHPR) during its 72nd ordinary session in August 2022, is an attempt to shift the burden of staying safe online from the shoulders of those who have been targeted with abuse.

ACHPR Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women in Africa, Commissioner Janet Ramatoulie Sallah-Njie, describes it as a “unique and comprehensively conceptualised” mechanism that paves the way for transformative change and could prove invaluable to women over time. She believes “the obligation on States to undertake awareness-raising programmes about the root causes of digital violence against women within the general context of gender-based violence will bring out changes in socio-cultural attitudes and remove gender norms and stereotypes.”

This exclusive African soft policy framework is the first of its kind to be introduced in the international arena. While scant attention is being paid to it, the resolution draws on the Maputo Protocol, which “guarantees every woman’s right to dignity and not to be exploited and degraded, and the protection of every woman from all forms of violence, particularly sexual and verbal violence.”

A compelling feature of the resolution, which includes nine recommendations, is the recognition of the varied forms of online violence ranging from cyberstalking, unsolicited sexually explicit content, doxing, cyber-bullying, and the non-consensual sharing of intimate images. The ACHPR, together with its partners, intends to commission a comprehensive study on the subject to create guidelines for states on the necessary elements to be addressed in their legal framework.

Mukwasi supports additional research on digital violence against women and its use in developing targeted, evidence-based interventions. She says States can incorporate recommendations from the resolution into national policies and laws, while civil society organisations (CSOs) across the continent could identify advocacy opportunities, such as conducting research or pushing for legislative reforms.

“The resolution draws on the Maputo Protocol which “guarantees every woman’s right to dignity and not to be exploited and degraded, and the protection of every woman from all forms of violence, particularly sexual and verbal violence.”

As a quasi-judicial body it is difficult to comprehend how the ACHPR will ensure compliance, but Commissioner Janet Ramatoulie Sallah-Njie points out the commission engages with state parties, and takes the opportunity to follow up on the implementation of the recommendations contained in Resolution 522. These include initiated promotion and protection missions. “The Commission engages with State parties through Urgent Letters of Appeal addressing human rights violations and measures taken under the African Charter to address such violations, including adoption of policies and domestication of international human rights treaties,” she explains. Submitted state reports could be disputed by CSOs through the submission of their shadow reports, she adds, providing another opportunity for CSO input.

“The resolution validates the work of CSOs… working towards women’s digital inclusion,” says Mukwasi. “It also complements all the work on violence against women because the internet is the new frontier for the war against women.”

February: The Africa region in brief

Nigeria constricts civic space, Mozambique weaponizes NGO law and Cameroonian journalists at risk

Cameroon: A hotbed for critical journalists

In the aftermath of the 2 February shooting death of Cameroonian radio presenter Jean-Jacques Ola Bébé, UN Human Rights spokesperson Seif Magango has urged authorities in the country to “take all necessary measures to create an enabling environment for journalists to work without fear of reprisal, and to uphold the right to freedom of expression as guaranteed in international human rights law, and also set out in Cameroon’s Constitution.”

Bébé, who was also an Orthodox priest, was a regular guest often featured on local radio stations for his critical views on rampant corruption in the country. Two days before he was killed, Bébé told Galaxy FM radio he had been receiving death threats, which he suspected were from authorities. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Bébé’s last appearance was on 2 February, the day he went missing, as a guest on the daily show “Boîte Noire” for private broadcaster Mo’o TV, where he spoke about the murder of Martinez Zogo.

Cameroonian authorities acted quickly in the case of Zogo and arrested a number of high-ranking security officers, including Léopold Maxime Eko Eko, head of the Directorate General for External Research – known by its French acronym, DGRE – and other members of DGRE. Several powerful businessmen with connections to high-ranking public officials were also arrested.

As Human Rights Watch says: “Justice for both Zogo and Ola Bébé will send a strong message that those who kill journalists will be held to account. But equally important, the government needs to actively protect journalists who strive to expose abuses. Journalism needs to stop being a high-risk profession in Cameroon.”

Nigeria: Broken election promises

Retired military general President Muhammadu Buhari promised to leave a legacy of free and fair elections, but Nigeria’s 2023 electoral landscape was fraught with insecurity, ethnic tensions, violence, corruption, a cash crisis and an inefficient electoral management body.

In preparation for what was the most highly contested elections in the history of Nigeria, IFEX members took precautions through their strategic initiatives to support safety of journalists. The International Press Centre put out a safety advisory for journalists, focused on professional and ethical standards and tips on maintaining well-being. The media code of ethics was also updated. In anticipation of the predicted violence against journalists, Media Rights Agenda set up a hotline for journalists to access support, advice about their rights, available safety mechanisms and legal support. Tracking the media and freedom of expression during the election, the Institute for Media and Society put out daily detailed violation reports from across the country.

The post-election pandemonium following the delayed results is reflective of the country’s highly charged political and electoral landscape, prior to polling day.

Along with the socio-political threats, has been the slow and steady decline of civic freedoms in Nigeria. In 2019, CIVICUS demoted Nigeria from obstructed to repressed in its People Power Under Attack 2019 report based on its assessment of freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association

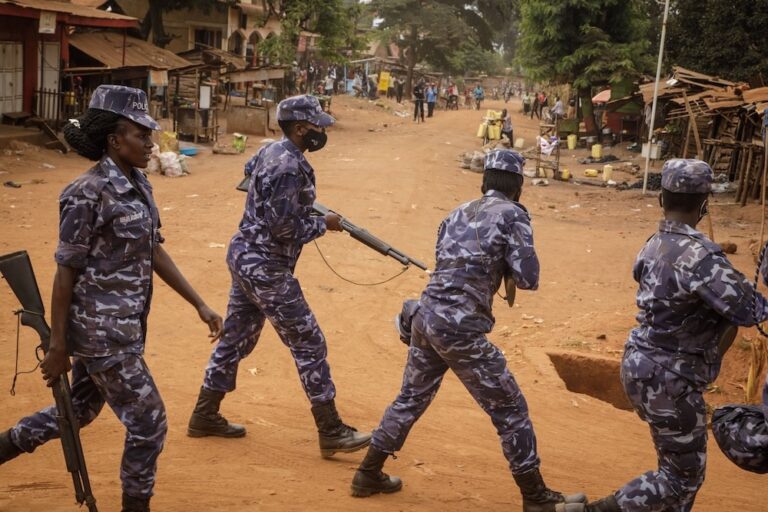

Online and offline spaces for civic engagement and democratic participation have been severely restricted through enactment of constrictive laws, including the 2020 Law on Interception of Electronic Messages (2020) and the Misuse of the Anti-Cybercrime Act of 2019, which has been used to harass and prosecute human rights defenders and journalists. The systematic crackdown on civil society demonstrations and excessive use of force and arrest of peaceful protesters has become a trademark of the authorities. Online harassment is an area of concern as the Nigerian government is quite sophisticated in surveillance.

There was also the promise of support for media freedom, but the Media Foundation for West Africa points out that attacks and threats on journalists and mass closure of broadcasters point to a government that has failed in that undertaking.

Tanzania: The beginnings of transformation

Just a month after Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan lifted a six-year ban on opposition party political rallies, the country is poised to review the restrictive Media Services Act of 2016.

Minister for Information, Communications and Information Technology, Nape Nnauye promised that The Media Services Act, 2016, would be revised and that the amendments would soon be tabled in Parliament.

CPJ reports that in 2019, in a landmark verdict, the East African Court of Justice ruled that numerous sections of The Media Services Act, “including those on sedition, criminal defamation, and false news publication, Resolution 522 and freedom of expression, and thereby breach the constitutive treaty of the East African Community.”

Reviewing restrictive legislation seems to be part of President Hassan’s strategy of Reconciliation, Resilience, Reforms and Rebuilding the nation, dubbed the 4Rs.

Mozambique: Thwarting the work of NGOs under the guise of compliance

Mozambique joins the growing list of countries using Financial Action Task Force (FATF) compliance to craft legislation that is more heavily focused on over-regulating non-governmental organisations than on tackling money laundering.

Emerging evidence indicates that under the guise of conforming to FATF recommendations, Mozambique’s Creation, Organization, and Operation of Non-profit Organizations Bill is more likely to be applied to restricting the activities of NGOs than regulating the financing of terrorist activities.

Over the last two years, southern African countries – namely Botswana, Zimbabwe, Namibia and now Mozambique – have controversially tabled laws drawing on FATF regulations.

In March 2022, a team led by the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) was dispatched to engage the Botswana government to reconsider their controversial Criminal Evidence Procedure (Controlled Investigations) Act. As the Association of Progressive Communications pointed out, the Bill “provides for invasion of privacy and … would enable the infringement of freedoms of expression and the media.”

Unfortunately the regional MISA chapter was not as successful in preventing the passage of Zimbabwe’s highly criticised Private Voluntary Organisation Amendment Act – which imposes severe restrictions while at the same time affording the Minister of Public Service and Social Welfare excessive and unfettered powers.