Nigeria's cybercrime law is more frequently being used against journalists, political activists and critics of the state instead of protecting citizens from cybercrime.

This statement was originally published on mfwa.org on 7 October 2020.

On February 13, 2020, Agba Jalingo, the publisher of the online newspaper Cross River Watch, regained tentative freedom after a Federal High Court in Calabar granted him 10 million Naira (about US$ 27,300) bail. The journalist had spent 174 days in detention after he was arrested and charged with felony and terrorism. The charges, the second of which is under Nigeria’s Cyber Crime Law, related to a story Jalingo published alleging diversion of state funds by the Cross River State government.

The only thing the story had to do with cyberspace is the fact that it was published online. Yet, that was the circumstance that aggravated the publisher’s “crime”. Jalingo’s ordeal is shared by many journalists and activists who have come to realise to their cost how grotesquely elastic Nigeria’s Cyber Crime Law can be. The law adopted in 2015, presumably to secure online security and privacy, to tackle cyber fraud and boost the country’s digital economy, has become notorious for its frequent manipulation by the authorities to silence criticism and dissent online.

Another journalist, Oliver Fejiro, has been battling a five-counts charge of “Cyber Stalking” punishable under the provisions of Section 24 of the CyberCrimes Act 2015. Fejiro’s troubles started in early 2017 after the news website Secret Reporters of which he is the founder and publisher, published a series of stories alleging corruption at Sterling Bank.

The Police arrested Fejiro in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, on March 16, 2017, and flew him to Lagos after an overnight trip by road to Umuahia, Abia State. Fejiro was arraigned before a Federal High Court in Lagos on April 28. The court remanded him until he satisfied bail conditions on May 11, 2017, and the case has since been dragging.

“The last time I was in court was February 2020. I was scheduled to appear again by May 28, but the COVID-19 saga has made it impossible,” Fejiro said in a recent WhatsApp interaction with MFWA.

On March 24, 2020, over 20 officers of the Department of State Services, (DSS) in Abia State stormed the chambers of a lawyer and human rights activist, Emperor Gabriel Ogbonna and arrested him. The activist had in a Facebook post, alleged that the Governor of Abia State, Okezie Ikpeazu, had gone to a shrine to swear an oath of loyalty and secrecy to his predecessor.

Ogbonna was put before a Magistrate’s Court in Umuahia on cyber terrorism charges on March 26, under Section 27(1) (a) and 18(1) of Nigeria’s CyberCrimes Act. He was subsequently remanded in custody. Emperor Gabriel Ogbonna was released on a 2 million Naira bail on August 18.

On May 8, four masked men from the Department of State Services (DSS) stormed the home of Saint Mienpamo Onitsha, founder of the news website Naija Live TV, and carried him away at gunpoint. Detained at DSS headquarters in the state capital Yenagoa, Onitsha was later informed that his arrest was in relation to his media outlet’s report on the alleged collapse of a COVID-19 isolation centre in Kogi State, a report they claimed to be false. The journalist was released on bail on May 12, 2020, after he apologised for the “erroneous” publication and denied having been kidnapped by the DSS. A day after his release, Onitsha issued a statement giving details of his Gestapo-style arrest and confirming that he was forced to issue the apology over the publication as a condition for his release.

The DSS again summoned Onitsha on June 4 over the same publication and detained him overnight. On June 5, the security agency arraigned the journalist before a federal court on charges of publishing false news under section 24(1) b of Nigeria’s CyberCrimes Act 2015. The Court granted bail to the journalist pending another hearing in October 2020.

On the same day, June 5, this time, before a Magistrate’s Court in Owerri, Imo State, the DSS arraigned a political activist, Ambrose Nwaogwugwu, on a six-count charge, three of them under the cybercrime law.

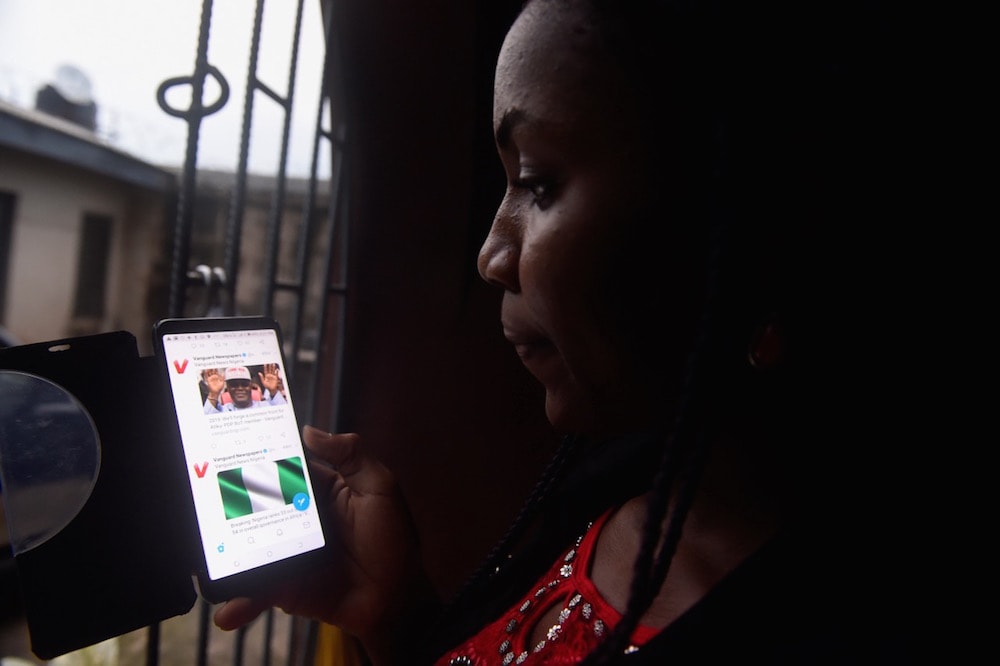

Ambrose Nwaogwugwu, who manages the New Media Centre of the Imo State Chapter of the People’s Democratic party (PDP), was arrested by the DSS on May 28, 2020 after he shared a Facebook post allegedly defamatory of Hope Uzodinma, governor of Imo State. The charge sheet, however, referred to a series of social media publications by Nwaogwugwu considered to be “false” and “insulting.” He was granted a N500,000 bail on June 22, 2020.

On May 22, 2020, the police in Kwara State arraigned before a Federal High Court in Abuja, the freelance journalist Rotimi Jolayemi, on a single count of causing annoyance, insult and hatred towards Nigeria’s Minister of Information and Culture, Alhaji Lai Mohammed, contrary to section 24(1)(b) of the CyberCrimes (Prohibition, Prevention etc) Act 2015.

The charge was in relation to a critical poem about the Minister which the journalist composed and shared on a WhatsApp platform. Jolayemi went into hiding after picking up intelligence that the police were after him over the poem. On May 5, he presented himself at the State Criminal Investigation Department of the Kwara State Police Command to relieve his wife and two other relatives who had been arrested more than a week earlier. He was released on bail on June 16.

Section 39 (1) of Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution guarantees freedom of expression; “Every person shall be entitled to freedom of expression. including freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart ideas and information without interference.”

Section 39(2) expands this right to cover press freedom by granting the right to establish mass media platforms.

“Without prejudice to the generality of subsection (I) of this section, every person shall be entitled to own, establish and operate any medium for the dissemination of information.”

To reinforce these rights, the country adopted a Freedom of Information Act in May 2011, to make public records and information freely available to the media and all citizens.

However, on the evidence of the above persecution on journalists using the CyberCrimes Act, one can conclude that the Act as presently interpreted by Nigeria’s criminal justice system threatens to take back the above-stated rights guaranteed by the constitution, with online journalists and social media activists being the biggest victims.

Section 24(b) of the law which has 59 sections is the provision often manipulated to target critical journalists and activists. The section prescribes a prison term of up to three years or a fine of N7,000,000 for persons who knowingly send, by means of a computer system, a message that they know to be false, for the purpose of “causing annoyance, inconvenience danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred, ill will or needless anxiety to another.”

Yet, the Cybercrime Act 2015 was primarily supposed to have been aimed at protecting vital economic infrastructure from cyberattacks, preventing fraud and fighting economic crimes.

“By the early 2000s, Nigeria had risen to notorious fame for the number and prevalence of cybercrimes from its residents,” Nigeria-based internet rights organisation Paradigm Initiative said in a policy brief titled Why Good Intentions May Not Be Enough: The Case of Nigeria’s Cybercrimes Act 2015.

A report by the National Communications Commission (NCC) also outlined some of the main cybercrime concerns in Nigeria. “Cybercrimes such as identity theft, obtaining by false pretense, fraudulent email blasting, cyber-dating scams, cyber blackmailing, piracy, hacking, phishing and spamming became widespread in the country with repercussions in the global landscape.”

It is thus safe to say that the Cybercrime Law 2015 was born out of a resolve to save Nigeria’s image as a hub for the above-mentioned nefarious activities. The collateral damage from its use by state officials and other powerful individuals to persecute critics is therefore too heavy a toll that offsets the benefits of the law.

The Media Foundation for West Africa MFWA is concerned that the infamous Section 24(b) of the CyberCrimes Act 2015 could undermine the good intentions of the Digital Rights and Freedom Bill (HB.490) which is currently on the floor of the House of Representatives. The bill seeks to guarantee human rights in Nigeria within the context of emerging digital technologies.

The Bill clearly warns that “…concerns about hate speech shall not be abused to discourage citizens from engaging in legitimate democratic debate on matters of general interest.” It further urges the courts “to make a distinction between, on the one hand, genuine and serious incitement to extremism and, on the other hand, the right of individuals (including journalists and politicians) to express their views freely…” (Section 13 (15,16).

With the CyberCrimes Act 2015 experience, these good intentions may well end up as a mere paper tiger. It is important therefore, for Nigeria’s criminal justice system to internalise the ideals espoused in the Digital Rights Bill when passed into law and to prioritise the promotion of free expression over the suppression of it to please parochial interests.