"Even in my writing, I was not able to speak in a straightforward manner. There were these red lines which we weren't able to go beyond, or speak about. But this aroused in me a counter-reaction which made me stronger, but also more miserable," says Syrian writer and journalist Samar Yazbek in an interview with PEN International.

Prior to the PEN Free the Word! event at the Hay Festival of Literature and the Arts in June 2013, Lauren Pyott caught up with the PEN Award-winning Syrian writer Samar Yazbek.

Below is Pyott’s interview with her for PEN International in which Yazbek spoke about her experiences working as a writer and journalist under Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

Before the revolution you worked as a writer, a novelist and a journalist, among other things. Can you speak a little about the interaction you had with the regime?

I had no relationship with the regime, I was always far from it and all that surrounded it. When it came to my writing, I spoke about the military and sectarian systems in Syria, which has led to so much destruction. In my novels, such as in Cinnamon, I wrote about the worlds of the poor and the rich and the desolation which society faces.

And I also participated in sit-ins. I had no relationship with the regime whatsoever, rather, I distanced myself from it. Not just politically, but even in terms of family and different groups. I always used to live independently, and alone.

In the film ‘As If We Were Catching A Cobra’, you spoke of the regime’s “intentional destruction of the individual deep inside us”. How did the regime affect you personally, as a writer, and as a member of society?

Of course it gave me great pain, and I always felt I was not a free person, but a sad one. I intended to leave the country, after a time. Even in my writing, I was not able to speak in a straightforward manner. There were these red lines which we weren’t able to go beyond, or speak about. But this aroused in me a counter-reaction which made me stronger, but also more miserable. When you live under the shadow of a dictatorial society, of course you have incredibly negative feelings. I believed change could come through literature; in novels, I felt I could really achieve something.

So did these red lines include ideas and subject matters? For example, I have barely found any books, or even allusions in literature, to the Hama massacre of 1982. How were you able to write about these political things?

There were no writers writing about that. There was a complete silence about what happened in several political events in Syria, so intense was the censorship. I didn’t even write about Hama, but it wasn’t my subject area. I wrote about the sectarian military and how they distorted and destroyed society. They wanted to transform Syria into a sectarian, ¬military, security state. This was something I knew how to write about and I was able to in a somewhat direct manner. But there were many episodes in Syria that were impossible to write about, as they’d have you killed. It is historically documented, and this is very important, that in the space of one week in 1982, Hafiz al Assad killed thirty thousand people and demolished Hama. He blamed the Muslim Brotherhood and banished individuals from the country through martial law.

No one could talk about it. Members of the leftist democratic opposition were put in jail for many years, and they were from various sects. So the margin of freedom was very narrow indeed. Several movements existed that were not visible, but there was a death of culture which extended to the destruction of the economy; the destruction of culture; the marginalization of intellectuals and the misuse of instruments of power. Those who were not in power weren’t able to do much. He [Hafiz al Assad] turned intellectuals into individuals who had uncooperative relationships with each other; they hated each other. He booby-trapped society; he blew up society; he made everyone hate each other. What Hafiz al Assad did, and what his son is now completing, is the destruction of the Syrian society over a period of forty years.

How have society and the relationship between people changed?

When the revolution started, it was a different situation. But Bashar al Assad tried to follow the same course as his father, just more intensively. From the very beginning it wasn’t a democratic society, it was founded on familial and sectarian principles. Corruption was rife because he created a security apparatus. He corrupted people. So when the revolution was born, all the sects came out, everyone came out. But he encouraged ‘criminal play-offs’ between peoples, pitting them against one another; he wanted to say that there was a sectarian war, and this just wasn’t the case. This is a people’s revolution. It was poor people and Muslims that came walking out. But Bashar al Assad and his security forces fostered these ‘criminal play-offs’ which led to fighting within society: to the withdrawal of certain sectarian groups and to the rising fears of the Christians. He wanted to stop the revolution but the revolution did not stop. The complete opposite happened; it continued. But he repressed it and killed people. He arrested them, starved them, and raped women. He demolished cities with airplanes. He killed women and said it was the Alawis who killed them.

But it was the complete opposite. He went to kill Christians saying that they were the rebels, and this wasn’t true. He made members of his mukhabarat – secret police – wear clothes marked ‘The Free Syrian Army’ and said it was them who had killed [the Christians]. And this wasn’t true. The most important thing is that the country has now been infiltrated by sectarianism. Despite this, until now a Sunni village has not massacred an Alawi village as Bashar had hoped would happen. He has carried out numerous sectarian massacres, at the hands of the sectarian shabiha – thugs. In al Bayda, Karam al Zeitoun, ‘Aqraba, Houla. There is a state of sectarian infiltration and we are in grave danger, especially now with the intervention of Hizbullah, invited by Iran into Qusayr.

When Hassan Nasrallah tried to encourage the Shi’a to fight against the rebels in Syria, in his speech he declared a sectarian war in the region. All these games that Bashar al Assad has been playing have led to a number of criminal transgressions. The sectarian massacres have themselves led to the intervention of some Jihadist groups. In my opinion, it is the Syrian regime itself which facilitated their entry, as well as other countries and some external funding. Regardless of the fact that the regime is crippling the other factions, the moderate Free Syrian Army is weaker anyway and they haven’t been supported with arms or funding. And so they have started to diminish, with help from the Jihadist forces. I am utterly convinced that the world – including the West, America and even the Gulf – the whole world saw that it was a civilian, democratic revolution and they wanted this revolution to fail. The morals of the whole world have fallen.

The whole world: the Western governments, the American government, the governments of the entire world have lost their morals and their conscience. They have witnessed people demanding their freedom. I have described what has been happening since 2011, and is still continuing to this day as a people’s revolution. There is already intervention, by means of a group of countries turning it into a sectarian war. The civilian and democratic movement has been culled for the purpose of turning it into a religious war. Even now, Syrians continue to resist. But personally I feel we are standing at the threshold of a very dangerous period, following the intervention of Hizbullah and Iran, fighting the rebels on behalf of Bashar al Assad’s forces. I feel we are now standing on the threshold of a very dangerous sectarian war.

So what can the response be? How to resist the violence that the regime is so desperately encouraging? Where is the space for a non-violent movement?

It was a revolution that started peacefully, and as I’ve said, I was there when it started. Now when I return to Syria and see what is happening, I see how it has been transformed into an armed popular resistance movement, and how some of the Islamist elements have infiltrated it. There is a different face to the revolution which the West doesn’t speak about. I’m going to tell you something very important: the Western media doesn’t know what is really going on in Syria. Why? Because they only see the aspects they want to see.

They see some Islamist factions, alien to Syrian society, which are now entering Syria and are trying to steal the revolution. [The media] doesn’t see the civil society initiatives in the revolution; they don’t see the civilian movement. There are peaceful demonstrations every Friday emerging from the cities. There are civil society initiatives and groups of civilian youth coming out. There is revolutionary art: drawing, graffiti, cinema, songs, literature, and poetry. No one is talking about this other face of the revolution; the world doesn’t talk about it.

I don’t know why. I think that it’s in the interests of the Western governments to maintain this false image of the Syrian revolution. Those governments don’t even feel ashamed to admit to the people they govern that they are democratic governments allowing people to be slaughtered, and allowing the biggest massacre which has occurred in modern history, and still continuing to this day.

I want to ask you about fear. In A Woman In The Crossfire you mention that there is something important to be taken from fear. What is that?

I’m going to tell you something: fear is a human thing. No one likes to admit that they are scared. But as far as I’m concerned, the hero of my book is fear. My hero is fear. Fear is a human and a true feeling; it is not false or fictitious. Our notion of heroism in today’s world is distorted. We call people heroes when they die and we call them heroes because they have died. We feel they have taken death from us. For example, we call martyrs heroes. But they have died. Rarely do we call someone a hero before he dies. Look at all of history, Greek tragedy or just personal tragedy in the course of history, the heroes are those young men and women who have died early for the sake of some cause. We only call them heroes if they’ve died. This, too, is some kind of brutality. It’s part of the human brutality which has no real connection with fear. Heroes get scared. And we don’t have to die to become heroes. We can be heroes whilst being scared, and whilst loving, and hating. We are human. So for this reason I say that fear is a human emotion that is very true and very honest.

In your book you often mention this difference between ‘myself’ and ‘herself’, and sometimes talk about yourself in the third person. Where do you find ‘yourself’, amidst this chaos?

To this day I have not been able to detach myself from this experience, I’m still immersed in it and I’m still observing and watching it. I’m now someone else, or, I’m now observing someone else. I think all Syrian men and women have changed. I led a completely different life and it was lived entirely through literature. I was isolated from people.

Now it’s a different situation. I’ve been observing a different person inside of me ever since the revolution started. I think that the ongoing violence and all that has happened has changed me a great deal. It’s even changed my relationship with writing. I’m now more inclined to have a connection with the problems of the people and to be engrossed in their situations rather than just writing about them. I think that some of the true intellects in the Syrian revolution, after this extreme violence, will join the civil society movement. They’re [following the thinking of] Gramsci; being part of the life of the people; participating alongside them in all manner of things; working with them; being part of their movement; and they’re seeing with their eyes what is being done. They’re not just talking about them. I have lost the ability to speak about people. Right now, I am not able to publish anything that I write. In truth, I really am immersed in the civil society movement. I can see that my role right now is important, and this is the role of the true intellectual. Rather than cursing all the mistakes of the revolution, and talking about them – every revolution has its mistakes – the intellectuals need to work at the heart of the revolution. They say that this is an Islamist revolution, but that’s not true. Be part of the revolution and it won’t be an Islamist revolution. Work with the revolution and you’ll be able to give it a more positive form. I see that there are great failings amongst the secular and cultural elites in all of the Arab revolutions.

So can you talk more about the role of the cultural figures? What is the role of art in bearing witness to violence?

I wasn’t disappointed with my book at the start of the revolution, and I am pleased with it to this day. We need books to document the revolution and to bear witness to it. Art changes life. These testimonies which I trust, are documenting the violence happening now in society. Bashar al Assad, the regime and all his friends around the world – and in my opinion the whole world is helping him – is saying the exact opposite of this. I feel that we need to record these eye-witness accounts. Many people have tried to condemn me for my book. They say that it isn’t true and such like. Not just the mukhabarat – secret police – but many people, and for different reasons, whether they be personal or political. But I am convinced that we need to write books whatever the reaction is. We need to write books which expose exactly what has happened. I published my diaries which go some way to explain how the Syrian revolution started, and how it started peacefully. I think it’s very important right now so that the world knows that [the protesters] are not terrorists, that they are poor, ordinary people asking for freedom. Therefore my relationship with art in this book, though not necessarily in general, is to convey an aesthetic, human message.

I need to go further and I will do that in other books, but not in an artistic way. On the contrary, I brought together the personal and the testimonial. I wanted to bring out a real book from the heart of reality, and everything in it is real. And so what of literary creativity in documenting the revolution? Of course there is poetry and singing and music, but I feel that this is not the time for the novel. I think it will need longer because of the vast amount of violence that’s come out of the revolution. Literature hasn’t been emerging in the way that it should have by now. I don’t even consider all that I have written to be literature, just testimonies. I need more time. There are some good poets but there have also been great young people writing about the revolution. Wonderful people. There still are. As a result of this extreme violence and the daily massacres, and the extensive destruction, art has changed from poetry and literature into photography and cinema and graffiti. That’s how it is. But I personally think that literature will come later, when the people are able to breathe a little. Right now people are living under perpetual death and blood and destruction.

You are also an activist and have set up your own foundation inside Syria, called “Suriyat min ajil al-tanmia al-insania” [Syrian Women for Human Development]. Can you talk a little about this?

After several trips across the north of Syria, I realised that we needed to make some kind of civil society based initiative in the countryside and be part of the people’s movement. And so I set up this organization. I think that it should be us Syrians setting up these civilian initiatives and organisations and not the West. We are setting them up and making them, and participating in them with the people and the youth. I am very concerned with the situation in the rural parts of the North. Society is currently facing extreme violence and is constantly resisting destruction. They are facing a deep psychological change, in the structure of the Syrian society. I believe that if we – and I mean everyone: both intellectuals and non-intellectuals – are not part of this society and the civil society movement, we will be in trouble.

What do you think about the next generation, the generation of your daughter and the children of the revolution?

I don’t really have a clear vision. There is no doubt that the next generation will have greater freedom, of course. But I also know that they will have severe problems on account of the violence, the destruction and the devastation.

So does your organization work with children?

Sometimes. Syrian children are now without schools. Some of them don’t even have any form of shelter, they move about the land. And so schools are one of the projects we have to work on, as are shelters. But this also includes arts projects, and theatre and so forth. This is very important as they have been living under violence, and killing, and massacres for a long time now. Children and women are always the victims of violence and wars. What I’m most concerned about, though, is the situation of women and their economic, social and educational development. But this is also difficult as the constant shelling prevents us from working. These people – human beings – are being shelled constantly. And so as a result our work is very hard. We are in desperate need for the shelling to stop so that we can start to make Syria flourish. But I fear that the whole world has let Bashar al Assad be. Even the areas that the rebels have liberated, with their blood, Bashar’s army then shelled from the sky. I meet with ordinary people, and with factions from the Free Syrian Army. I’m trying to understand what is going on. I need to see with my own eyes to understand what is going on in the country. Naturally, I meet with different types of people, of course. Even with Islamist factions. I need to meet with them and see them so I can understand what is happening in the country. We all need to know what is happening in the country.

What do you feel when you meet with these people? Do you find hope there?

My feeling about Syrians is that they are heroes, both men and women. Truly. They are still resisting. They’re resisting the killing, and the starvation. They’re resisting the corruption and the break-up of society. They’re resisting the sectarianism. But they have been forsaken. In my opinion, the Syrian people are wonderful and their revolution is wonderful. But they are very unfortunate. They have been placed in the hands of the worst dictator in the world and amongst the interests of conscience-less and moral-less nations. The whole world has trampled on their revolution. But despite that, when I see people, people who I’ve really seen with my own eyes, I see that they are great people. They don’t want war or peace, they don’t want violence, or sectarianism. They have very simple demands: justice and dignity. The whole world has come in with its own idea and they are stealing everything. They are trying to present it as a religious revolution and the people are resisting. But how long can they keep going? Of course they can’t continue resisting forever, because they have been forsaken.

To listen to Samar Yazbek’s talk during her PEN International Free the Word! event in June, see here.

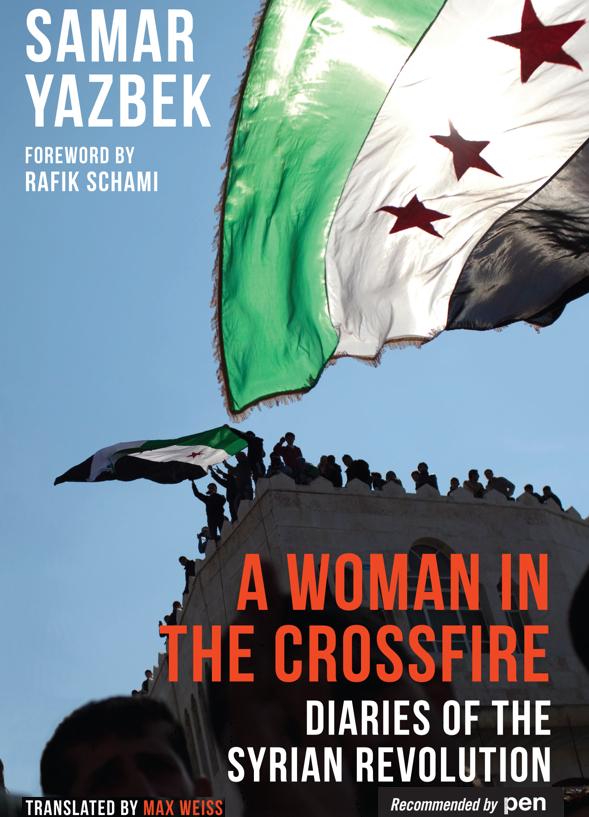

‘A Woman in the Crossfire’ is a diary of Samar Yazbek’s personal reflections on the first four months of the Syrian revolution and her part in itSnapshot of the cover of ‘A Woman in the Crossfire’