It’s no secret that the Pacific Islands will face rising sea levels, coastal flooding, and deadly storms as a result of climate change, a fact reiterated in this week’s report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Unfortunately, few people realize that these island nations are also home to a disappearing press sector. While […]

It’s no secret that the Pacific Islands will face rising sea levels, coastal flooding, and deadly storms as a result of climate change, a fact reiterated in this week’s report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Unfortunately, few people realize that these island nations are also home to a disappearing press sector.

While the tourist industries in countries like the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau have benefited from their sandy beaches, palm forests, and stunning atolls, local journalists and news agencies often struggle to make ends meet. Financial problems, old and rundown infrastructure, and poor training can critically undermine the development of a viable media sector.

Take the nation of Kiribati, an archipelago in the Central Pacific that is home to just over 100,000 people. In 2012, the country’s only news radio station was forced to shut down due to a broken transmitter; frequent power outages and a lack of backup generators have crippled the struggling audiovisual sector. The country’s remote location and scattered islands make it especially vulnerable to damage caused by storms, and repairs to communications equipment can take months and even years. Democratic Kiribati may not have the censorship apparatus of an authoritarian state, but for thousands of residents who are cut off from news and information, the effects can be similar.

Environmental sustainability has taken center stage in the Pacific Islands, but financial sustainability may be an equally urgent problem. At least four newspapers have closed on the island of Nauru in the past decade, citing financial reasons. Tuvalu’s only newspaper, Tuvalu Echoes, shut down in 2013 due to high operating costs. Given the country’s gross domestic product of about $3,500 per capita and a general dependence on imported goods, the cost of printing and ink can be prohibitive.

Some islands are somewhat better off. News consumers in Palau, for example, enjoy a number of broadcast and print options, both private and public. Yet reporters still lack formal training and qualifications, and practice journalism on an ad hoc basis. The College of Micronesia recently suspended its journalism program due to staff shortages. These economic challenges explain why many Pacific Island nations, although they are ranked Free in the most recent edition of Freedom House’s Freedom of the Press index owing to favorable political and legal environments, often hover near the border of the Partly Free category.

Taken alone, these are worrying developments. However, they loom especially large at a time when climate change threatens the livelihoods of Pacific Islanders and perhaps even the continued existence of their nations. The press is critical to educating the population about climate dangers, including high tides, cyclones, and other risks. For instance, Tuvaluans are less aware of the realities of climate change than most outsiders, according to interviews conducted by the Pacific Media Assistance Scheme. The news media can also facilitate emergency preparedness by transmitting life-saving information, such as alerts to seek higher ground.

There are some encouraging signs on the horizon. Satellite television has enabled many residents to access information and news programs from Asia and Australia. The internet is also accessible for some, though it usually reaches only a small percentage of the population, and service is spotty. On the Marshall Islands and Vanuatu, churches distribute newsletters and operate radio stations on a nonprofit basis, often raising awareness about climate issues. Several regional news outlets have begun operating in recent years under the auspices of the Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand, the University of Hawaii, and the Pacific Islands Development Program, which produces the Pacific Islands’ Report.

However, greater attention is needed from international donors and development agencies to ensure that local media don’t disappear entirely. Development efforts must be context specific. In the past, agencies such as Australia Aid and the Japan International Cooperation Agency have provided startup funding to island newspapers only to see them close after a few years due to financial problems. Unless donors are prepared to provide long-term funding, it may be that the traditional model of professionalized news media is becoming obsolete.

As an alternative, aid organizations could prioritize community-based approaches. For example, they might consider increasing the number of media trainings and grants to local community groups, including churches and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), which already have an active community following. At the same time, pluralistic private media ownership should be encouraged, as the World Bank recently did with a $3 million grant to diversify the Marshall Islands’ telecommunications sector.

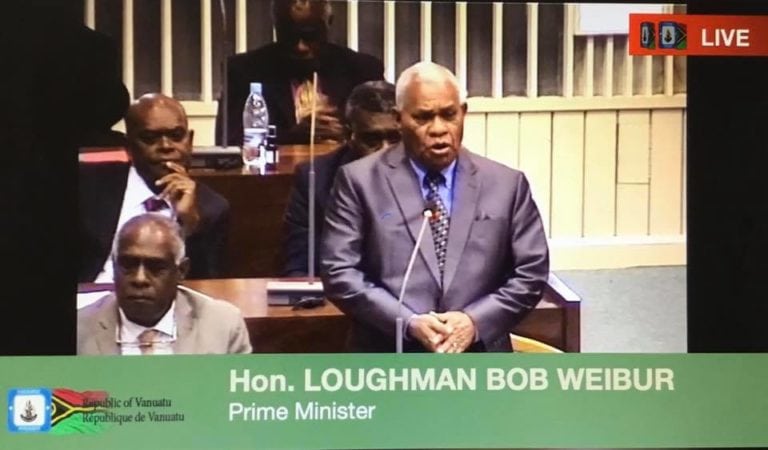

Finally, donors and local governments must continue to develop national and supranational emergency-response systems, which can have the secondary effect of making media infrastructure more resilient even in ordinary times. At the national level, Vanuatu recently established a National Disaster Management Office to coordinate with media, NGOs, and government ministries in the event of a climate-related disaster. This kind of coordination is critical to the quick dissemination of emergency information and might be used as a model for other island states.

At the intergovernmental level, the Pacific Media Assistance Group is developing the Pacific Emergency Broadcast System, or PEBS, in order to provide a collaborative platform in the event of crisis or disaster. Ongoing activities include the development of an early warning system for broadcasters, establishing backup broadcast systems, and drawing up country-specific disaster plans in collaboration with local stakeholders.

It would be a tragedy if those countries that stand to be most affected by climate change were allowed to remain the least prepared to cope with its consequences. More international donor attention and creative development strategies are needed to ensure that news organizations in the Pacific don’t vanish long before the islands themselves.

Reports by the Pacific Media Assistance Scheme contributed to the research for this post.