May 2024 in Asia-Pacific: A free expression round-up produced by IFEX's regional editor Mong Palatino, based on IFEX member reports and news from the region.

Media-related killings and attacks intensify in Pakistan, AI threatens elections and democracy in India, Indonesia plans to restrict investigative journalism, a landmark ruling on red-tagging in the Philippines, and Pacific groups underscore the importance of having a free press in protecting the environment.

Impunity: Four journalists killed in Pakistan, others threatened, detained, or missing

Intensified attacks against the media reflect the worsening state of impunity in Pakistan following the divisive February 2024 election.

Four journalists were killed in Pakistan while cases of attacks and threats targeting the media were also recorded over the past month.

Khuzdar Press Club President Maulana Muhammad Siddique Mengal was killed in a magnet bomb attack on 3 May in Balochistan. IFEX member Pakistan Press Foundation (PPF) reported that Siddique was also attacked in August 2023 but authorities failed to act accordingly. “The failure to investigate that incident properly and provide security undoubtedly emboldened the attackers responsible for his death,” PPF said in a statement.

On 15 May, Daily Khabrain reporter Ashfaq Ahmad Sial was gunned down by two masked motorcyclists in Punjab province. On 21 May, online reporter Kamran Dawar was killed in front of his home in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. On the same day, Awami Awaz reporter Nasrullah Gadani was critically wounded in an armed attack in Sindh province before he died three days later.

ARY news TV anchor Syed Iqrar ul Hassan and his three crew members were attacked by a group of people in Gujranwala city in Punjab. Another prominent TV personality, Hamid Mir – known for espousing free speech – shared that he had received death threats and online harassment. Kashmiri journalist Syed Farhad Ali Shah was taken from his home and went missing after his critical reports on the raging protests in Pakistan-administered Kashmir. And two Pakistani journalists were detained when they tried to stop a police raid at the Dera Ghazi Khan City press club.

Media groups have urged authorities to urgently investigate these incidents and strengthen mechanisms to protect journalists.

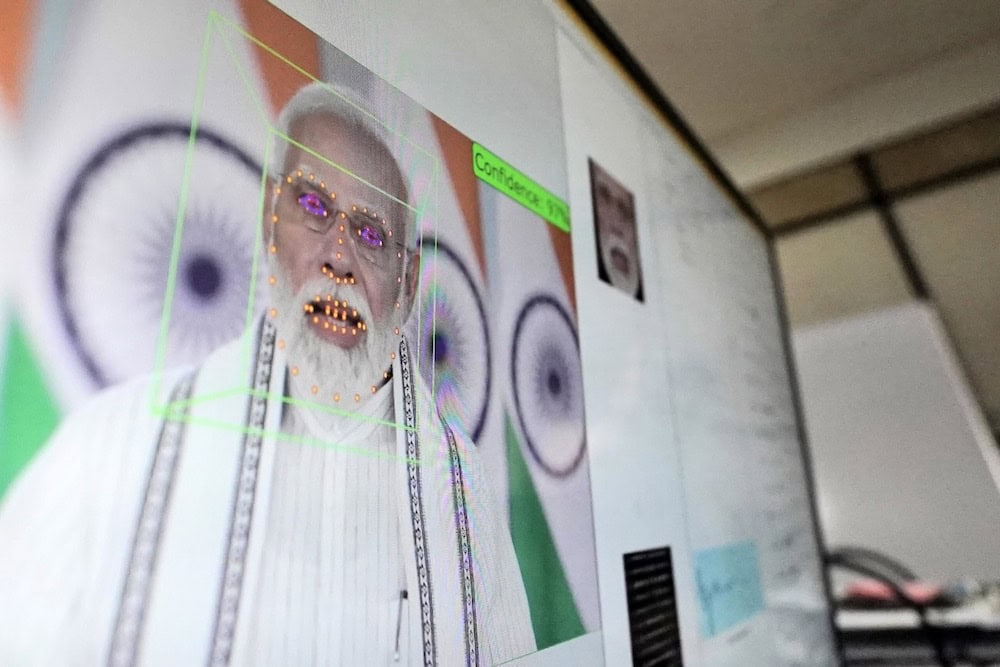

AI and India’s election

The recently concluded election in India saw the widespread use of AI tools aimed at influencing the decisions of voters. AImost all major parties featured AI content in their campaign materials, which included the adoption of deepfake technology. Journalist Hanan Zaffar pointed out the alarming ways in which “troll accounts subscribing to the ideology of different political parties are also employing AI and deepfakes to create narratives and counter-narratives.”

The government issued advisories on the regulation of AI but these proved inadequate in addressing its misuse. Mishi Choudhary, founder of IFEX member SFLC.in, told India Today that “efforts put into formulating and passing regulations remain nullified without stringent execution and enforcement.”

In another interview with The Economic Times, Choudhary highlighted the essential, collective role of various stakeholders in countering the harmful impact of AI.

“Fact-checking organisations, citizens, vernacular language experts, newsrooms and commercial experts need to be trained to check election mischief. Media organisations, too, must work together to share information, have a common number to report on deepfakes, identify coordinated campaigns, and reject them collectively. We must push for the provenance and labelling of synthetic media. We do need better training on tool-specific detection portals and collaboration.”

Concerns over repressive media laws and regulations

Punjab Defamation Bill. In Pakistan, more than 80 groups and individuals have signed a statement expressing grave concern over several provisions of the bill, which was eventually ratified by the Punjab provincial assembly. The statement warns that “the bill’s provisions, such as allowing defamation actions to be initiated without proof of actual damage and imposing extortionate fines, amount to nothing less than legal intimidation tactics.” IFEX member Bytes for All issued a separate statement highlighting the provision that empowers authorities to suspend or restrict social media accounts as it “raises concerns about government overreach and censorship in digital spaces.”

Indonesia’s Broadcasting Bill. IFEX member Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) Indonesia is among those who are opposing the planned revisions to the country’s Broadcasting Law. The bill pending at the House of Representatives puts restrictions on investigative reports and the broadcasting of LGBTQI+ content, including “negative behaviors or lifestyles that could potentially be imitated by the public.” AJI chairperson Nani Afrida said that “by curbing the ability of journalists to conduct and broadcast investigative work, the government is effectively trying to silence critical voices and limit public scrutiny.”

Papua New Guinea’s ‘media control policy’. Papua New Guinea’s “media development policy”, which was introduced in 2023, was recently deliberated in parliament with journalists sharing their perspectives and recommendations. The president of the local media council warned that “the proposed model would allocate too much centralised power to government.” In an interview with BenarNews, journalist Scott Waide explained the initial objection of media groups regarding the media policy.

“We’re calling it the ‘media control policy’, not the ‘media development policy’. We didn’t agree with it because it was trying to make the media an extension of the government public relations mechanism.”

Court rulings and ramifications

In Hong Kong, the Court of Appeals sided with the government in banning the broadcast of the 2019 protest anthem “Glory to Hong Kong”. A lower court had earlier ruled that the ban posed a chilling effect on free speech. Authorities banned the song, whose lyrics include the banned slogan “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times,” after it was mistakenly played in global events as a national anthem over 800 times. It should be noted that the 2019 protest movement did not in fact advocate for the independence of Hong Kong. Michael Caster of ARTICLE 19 described the ban as a “blatant example of Hong Kong’s embrace of digital repression.” He urged global tech companies to “speak out immediately against attempts to control internet intermediaries and broader efforts to use national security laws as a pretext for censorship and surveillance in Hong Kong.”

In Cambodia, civil society groups deplored the “unjust decision” of the Supreme Court, which upheld the conviction of union leaders who led a peaceful strike against mass layoffs at Naga World casino. They accused Phnom Penh authorities and security forces of resorting to “judicial harassment” and physical violence to disperse the non-violent strike of workers.

In Malaysia, the High Court directed Sarawak Report editor Clare Rewcastle Brown, who is based in London, to be present in court proceedings if she wants to appeal her defamation conviction. Brown was sentenced to two years in prison after she was found guilty of defaming the sultanah of Terengganu. Meanwhile, another defamation case against Brown was dismissed on a technicality after the allegedly libelous article was not translated in Bahasa. The case can still be appealed.

Good news in the Philippines

The Philippine Supreme Court released a landmark decision declaring red-tagging a threat to people’s life, liberty, and security. Before the ruling, authorities had insisted that the practice of linking activists and critics to armed communist groups is not a threat to civil liberties. Human Rights Watch said that the court decision “acknowledges the suffering of countless victims of this government policy.” Related to this, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines has produced a new study that documents at least 159 incidents of red-tagging against individual journalists, newsrooms, and media organisations since 2016. The study showed that more than half of the red-tagging cases were perpetrated by state forces.

Meanwhile, another confessed killer of radio journalist Percival Mabasa was convicted by a local court and sentenced to up to 16 years in prison. Despite the conviction, the suspected mastermind remains at large. Shawn Crispin, senior Southeast Asia representative of the Committee to Protect Journalists, called for the immediate arrest and prosecution of all suspects:

“The cycle of impunity isn’t broken by partial justice; it requires full justice.”

Pacific media groups speak out on press freedom and the climate crisis

Media groups across the Pacific marked World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) by emphasising the role of upholding the right to information in addressing the impact of the climate crisis in the region.

The theme of WPFD this year, “A Press for the Planet: Journalism in the Face of the Environmental Crisis,” resonates with the work being done by media groups in the Pacific. Robert Iroga, chair of the regional media watchdog and IFEX member Pacific Freedom Forum, underscored the need for media coverage and inclusion of Pacific journalists at global climate conferences.

Pacific Islands News Association President Kora Nou asserted that journalists should have an active role in implementing initiatives that seek to address the harsh impact of climate change.

“Journalists must be included in projects not merely as observers but as active participants, providing independent and objective coverage that uncovers the truth, expose wrongdoing, and amplify the voices of marginalised communities.”

In a WPFD editorial piece, Australia’s Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance Federal President Karen Percy cited the weaponisation of laws that undermine the work of media.

“When whistleblowers are prosecuted for revealing wrongdoing by governments and corporations; when defamation is weaponised to prevent scrutiny; when information that should be publicly available is inaccessible or wrongly marked top secret; and when the basic role of journalism is criminalised on ‘national security grounds’ – then it is the public who loses out.”