Aliansi Jurnalis Independen documents violent attacks and threats of layoffs plaguing Indonesian media in the past year.

This statement was originally published on seapa.org on 4 May 2018.

Last year, 2017, was marked with a number of distressing facts with regards to the Indonesian press – its freedom, professionalism, and labor-related issues.

The country’s sociopolitical dynamics is widely considered to be one of the contributing factors to Indonesia’s international press freedom ratings, including the country’s ranking in the Reporters Without Borders (Reporters Sans Frontières, RSF) index. While Indonesia’s ratings have improved in the past five years, the country still falls behind a number of other countries in Asia.

Indonesia ranked lower on the RSF 2017 press freedom index than several other Asian countries, including South Korea (ranked 63rd, with a score of 27.61), Japan (72nd, score 29.01), Hongkong (73rd, score 29.46). Indonesia even fell behind its former 27th province, East Timor, which scored 32.82 and sat at the 98th rank, 26 positions above Indonesia.

The good news is – Indonesia’s ratings were still higher than those of several neighboring countries, namely the Philippines (ranked 127th, with a score of 41.08); Myanmar (131st, score 41.82); Cambodia (132nd, score 42.07); India (136th, score 42.94); Sri Lanka (141st, score 44.34), Thailand (142nd, score 44.69); Malaysia (144th, score 46.89); Bangladesh (146th, score 48.36); Singapore (151st, score 51.00); Brunei Darussalam (156th, score 53.72); Laos (170th, score 66.41); Vietnam (175th, score 73.96); and China (176th, score 77.66).

Indonesia’s press freedom rankings according to RSF from 2007 to 2017:

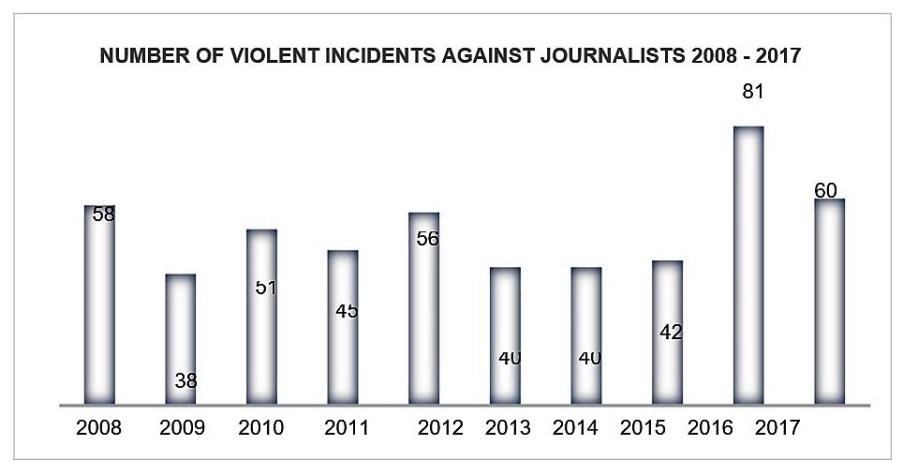

One of the main indicators of Indonesia’s press freedom situation is the number of violent incidents against journalists and the media. This parameter reports the number of physical violence, obstruction of journalists from reporting, confiscation of equipment and data, etc. Based on the data from AJI Indonesia Advocation Division, there were 60 cases of violence against journalists in 2017, making it the second highest figure in the past ten years.

Most of the incidents of violence against journalists took the form of physical attacks, which accounts for as many as 30 incidents. This was a repeat of 2016 where most of the incidents involved physical attacks with 36 cases and in 2015, 20 cases. The second highest type of violence was expulsion or obstruction of journalists from reporting, which numbered 13 cases. In 2016 this was also the second highest type of violent incident, with 18 cases. Third on the list was threat of violence or terror, which numbered six cases.

Local residents were responsible for most of the violent incidents against journalists, with involvement in 17 of the cases. This was hardly a new development. Local residents were involved in 26 incidents of violence in 2016, 17 in 2015, 10 in 2014, and 13 in 2013. So for five consecutive years, locals had committed the most number of violent incidents against journalists. The second highest number of perpetrators came from among the police (15 cases), followed by government officials (seven cases).

Labor-related issues

The year 2017 also recorded a number of distressing trends: sluggish media economy and the resulting wave of downsizing. Among the cases that had drawn the most public scrutiny were the layoffs in the media industry. The following table lists labor-related cases that took place in 2016, the aftermath of which had continued well into the following year.

Media downsizing 2016 – 2017

This issue was further compounded by the lack of labor unions in the media industry. Indonesian labor law prescribes the establishment of labor unions to advocate employees’ rights and interests. However, data from AJI and the Indonesian Federation of Independent Media Workers’ Unions (FSPMI) indicated that up to 2017 only 25 media workers’ unions had been established across Indonesia, a mere one percent of the total number of media organizations in the country.

Ethical and professional issues

One of the most glaring indicators of Indonesian press performance is the number of complaints filed with the Press Council. For the past eight years, the number of cases continues to follow a rising trend. A significant increase began to show in 2014, a tendency which was sustained up until 2017.

According to the Press Council, they had received around 600 complaints in 2017, with nearly the same figure the previous year. The complaints were mostly lodged on the basis of unbalanced content, condemnatory content, and fallacious content – which went against the Indonesian Journalistic Code of Ethics (KEJ).

Potential threat from laws and regulations

A number of laws and regulations have proven to be disadvantageous for the Indonesian press. These included the Criminal Code, State Intelligence Act, Anti-pornography Act, and the Information and Electronic Transactions Law. Out of the four laws, the 2008 Law No. 11 on Information and Electronic Transactions, which was revised on 21 December 2015, presents loopholes that might potentially be a threat to freedom of the press. Among these is the article that grants the government the authority to block a site without due process of law.

In addition to the Information and Electronic Transactions Law, the Broadcasting Bill currently being deliberated might pose yet another threat to the media business in the country. As a member of the National Coalition for Broadcasting Reform (KNRP), AJI regarded the progress of the deliberation with a measure of apprehension. The most crucial item in the bill is the issue of multiplexer system in digitalization, which had caused another delay in the bill enactment. The delay resulted from the stalemate at the joint meeting between the Legislative Committee and the bill initiator, House Commission I, on 3 December 2017. The deadlock had arisen during the deliberation on arrangement of migration toward digital broadcasting with regards to selection of multiplexer operator.

The 3 October 2017 draft of the Broadcasting Bill specified that the migration from analog to digital broadcasting will be conducted by a single multiplexer, with the Public Broadcasting Agency acting as the multiplexer operator. Reaffirmation for this clause was given in a poll on the working committee level, where five House factions had voted for the single multiplexer system, four had voted in favor of multiple multiplexer system, and one faction was absent. And yet, when the plenary session was due to be held for the final vote, suddenly one of the House factions, followed by a number of others, chose to withdraw from the decision-making process.

AJI is of the opinion that in view of the public interest the single multiplexer (single-mux) system for digital broadcasting, with the state as the authorized operator, is the best option in this case, based on a number of reasons. The single-mux system allows for spectrum efficiency for commercial broadcasting, leaving enough frequency for non-commercial and non-broadcasting communication purposes. In this way, it is expected that migration to digital broadcasting will provide equal and fair business opportunities and broadcasting arrangement for the public. In addition, the public will benefit from the use of digital broadcasting to support non-commercial interests including education, health, children’s programs, and disaster mitigation.

For additional graphs, please refer to the statement published on seapa.org

Data from https://advokasi.aji.or.id/