The last ten years have shown no progress in addressing the fundamental reason for the persistence of impunity in the Philippines, and its consequent encouragement of the killers of journalists and media workers.

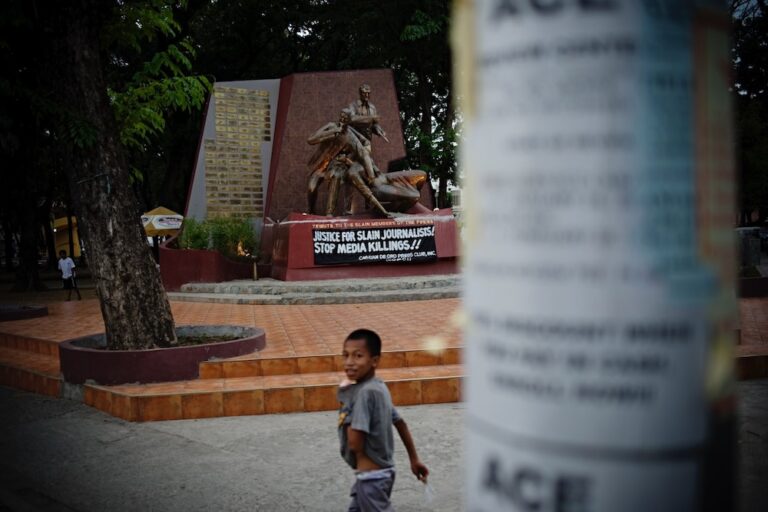

This year marks the 20th year since the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared May 3 World Press Freedom Day. May 3 continues to resonate with irony in the Philippines, where, since 1986, or seven years before the declaration, the killing of journalists and media workers has continued, peaking in 2009 when 32 were killed in the November 23 Ampatuan Massacre.

Since 2002 when Pagadian’s print and broadcast journalist Edgar Damalerio was killed in that city, the persistence of impunity – the exemption from punishment of wrong-doers – has been attributed to the weakness of the justice system, specially at the local level, which results in the failed prosecution and even non-prosecution of the killers of journalists.

That weakness is based on the collusion with the masterminds, and sometimes even the direct involvement, of police and military personnel in many of the killings. But the shortfall in the number of prosecutors and judges, and some prosecutors’ fear of retaliation by local tyrants, have also contributed to the failure to prosecute most of the killers and all of the suspected masterminds.

The last ten years since Damalerio was killed have shown no progress in addressing the fundamental reason for the persistence of impunity, and its consequent encouragement of the killers of journalists, primarily because doing so will require fundamental reforms at the investigative, prosecutorial, and judicial levels.

Police capacity to investigate the killings – to respond speedily to attacks on journalists, to gather the evidence needed to develop strong cases, and even to preserve whatever evidence is available or has been gathered – is only one of the areas that need reform.

Equally and perhaps even more urgently needed is the re-orientation of the police away from criminal involvement with local politicians and other interests, together with the development among them of an awareness and appreciation of, rather than indifference and even hostility to, the press and journalists. To help halt the killing of journalists, the police not only have to become more competent and less corrupt. They also need lessons in the culture of democracy and the indivisible role of the press in it.

The recruitment of more state prosecutors and judges to fill the shortfall in their numbers would also help. But it has proven easier in the telling than the doing, among other reasons because for many lawyers, government service is not as lucrative and inviting as private practice.

Even the solution of that problem is not likely to miraculously result in the successful prosecution and punishment of most of the killers of journalists and the brains behind them. As some of the country’s legal educators have pointed out, the law curriculum that produces lawyers also needs reform towards a greater emphasis on the law as an instrument for the enhancement rather than the constriction of free expression and press freedom. Among this country’s needs is a corps of lawyers committed to the defense of free expression and the prosecution of those who savage it.

Other factors also feed into the persistence of the culture of impunity. Warlordism, as the Ampatuan Massacre demonstrated, is a major concern in some 100 places all over the country where powerful political families have ruled for decades and have developed a culture of unaccountable power.

Although a direct correlation between warlord dominance and the killing of journalists has yet to be established by research, anecdotal evidence suggests that in at least some cases such a correlation exists, especially during election periods when journalists at the local level are drawn into involvement in the often lethal struggles for power among political clans.

Like the rest of the citizenry, journalists do have their preferences during election periods and are entitled to them. But because of the power inherent in the media, their involvement in the campaigns as partisans, or, in some cases, their being candidates themselves while continuing to discharge such journalistic duties as reporting or commenting on such events as elections, has put them in danger. Indeed, among the journalists who have been killed since 1986 were block-timers broadcasting in behalf of their politician-patrons or who were block-timing for themselves as candidates.

Inevitable that such involvements, particularly at the local level where violence during elections has been a fact of life for decades, have often led to the killing of journalists who’re perceived as either biased for certain candidates, or as using the profession to further their own political ambitions.

The ensuing conflicts of interest – between the journalistic responsibility of enhancing citizen capacity to form opinions and make decisions on the basis of sound information, and the personal interest inherent in running for office – and perceptions of partisanship are not the fundamental causes behind the persistence of the culture of impunity. And while murder is not a just response to conflicts of interest or any other professional or ethical lapse on the part of those who do journalistic work, the reality on the ground, where violence is often the first and last resort in the resolution of political rivalries, says otherwise.

But in this reality lurks at least a partial answer to the problem of impunity. As complex and as difficult are the solutions needed to address the culture of impunity and to finally put a stop to the killing of journalists, there is enough room for those who regard themselves as journalism professionals to help themselves – and that is, by expending both effort and care in evaluating the ethical and professional implications of the decisions and choices they are called upon to make before they make them.

It has been said before, but bears saying again. Ethical compliance and professionalism are the best protection for those who regard themselves as journalists and true professionals rather than as the instruments of political interests or as politicians themselves. Journalists can’t be politicians at the same time, and neither can politicians be journalists without compromising both callings. To be both in this country is not only to attempt the morally impossible; it is also to court disaster.