The situation for freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and association in Russia has deteriorated since the re-election of Vladimir Putin in March 2012. The main issues of concern are repression against Russian NGOs, strict anti-blasphemy laws, increasing limits on digital freedom, and the banning of “homosexual propaganda”.

The situation for freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and association in Russia has deteriorated since the re-election of Vladimir Putin in March 2012. The main issues of concern are repression against Russian NGOs, strict anti-blasphemy laws, increasing limits on digital freedom, the banning of “homosexual propaganda” and the re-criminalisation of libel.

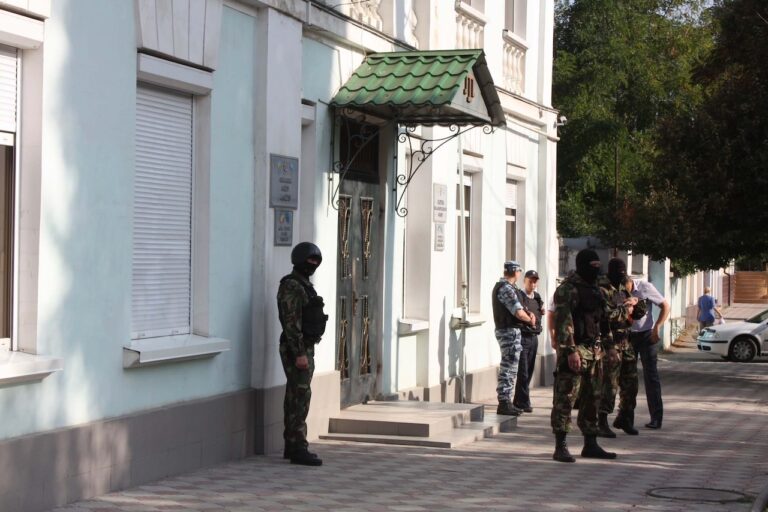

Amendments to the law on Non-Governmental Organisations, adopted in July 2012, forced all NGOs that receive funds from abroad to register as “foreign agents” (a highly charged phrase, synonymous with “spy”) if they are involved in “political activities”, the latter term being very broadly defined. During March 2013, dozens of NGOs in Russia were inspected to determine whether their activities comply with current legislation. This potentially endangers the activities of NGOs in Russia including those working on freedom of expression and human rights groups.

Freedom of religious expression has been compromised through anti-extremism legislation that allows selective implementation of its ambiguous definitions. An anti-blasphemy law that provides for prison terms or fines for offending religious feeling was passed by Russia’s parliament in April 2013.

The attitude of the authorities to whistle-blowers has been highlighted through the authorities’ posthumous trial of lawyer Sergei Magnitsky. Magnitsky investigated cases of corruption among high-ranking Russian officials; he died in prison in 2009 in pre-trial detention and no one has ever been charged with his death.

Freedom of expression in the LGBT community has been restricted after the State Duma adopted a law prohibiting the promotion of homosexuality. Similar laws were previously introduced at the regional level in 11 administrative entities of the Russian Federation, including the second largest city St. Petersburg.

Media Freedom

Russia continues to be one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 54 reporters have been killed in Russia since 1992, with 16 cases still unsolved. Impunity remains a significant problem for journalists: on-going threats of violence are rarely investigated properly by the authorities. The killers of Natalia Estemirova, Abdulmalik Akhmedilov, Khadzhimurad Kamalov and other prominent investigative reporters have never been prosecuted; nor have the organisers of Anna Politkovskaya’s murder.

In July 2012, criminal libel was reintroduced by the State Duma into the criminal code after being decriminalized in November 2011. Defamation laws are used to silence the press. Dmitry Muratov, the editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta, says courts are used as a censorship instrument in Russia. His newspaper lost three libel appeals in just one week in November 2011, all issued by the Department of Presidential Affairs after they published investigative journalism into federal budget spending.

Other legislative challenges to media freedom in Russia include a law on high treason that endangers Russian journalists who work for the international media, as it prohibits providing information to foreign countries, and a law that forbids the media from using obscene words. Another draft law will classify media outlets that receive more than 50 per cent of their revenues from abroad as “foreign agents”.

The genuine diversity of media ownership in Russia is questionable. Opinion polls by the Levada Centre show that 69 per cent of Russian citizens consider the three state-owned TV channels to be the primary source of their information. Most of the other national media outlets are either co-owned by the state, or belong to oligarchs who have relationships with the Kremlin. Several top managers and editors recently were fired or resigned from their positions in Kommersant and Gazeta.ru in protest against their owners’ intrusion into editorial policies. Several independent online publications critical of the authorities were closed down by their owners.

The lack of independent political and investigative reporting is not likely to be rectified by the launch of a new channel “Public Television of Russia”, scheduled for May 2013. While the new channel has been described as a public service broadcaster “equally independent from the state and advertising”, it will in fact rely on government funding. Furthermore, its CEO is appointed directly by the President of Russia, casting further doubts over its editorial independence.

Digital Freedom

As internet use grows in Russia, the authorities have introduced new restrictive laws that challenge free expression online and allow filtering and blocking of content. Federal Law No. 139-FZ, adopted in July 2012 created a blacklist of sites with “harmful” information under a pretext of child protection. The law suggested broad and ambiguous definitions that allow extrajudicial censorship of online content. Roskomnadzor, a dedicated state agency, compiles a black list of web-pages that contain child pornography, “extremist materials” and information on suicide or drug use. ISPs are obliged by the law to block all the blacklisted web-pages.

Extensive online censorship is accompanied by surveillance of Russians’ online activities. SORM, a nation-wide surveillance system, operated with Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technology, allows the state security force not only to control, but even to intrude into the internet traffic of any internet user in Russia without any special permit or court decision.

There was a series of cyber-attacks on the websites of independent Russian media outlets, such as Kommersant, Ekho Moskvy, Bolshoi Gorod, Dozhd’ TV and Slon.ru, during the street protests in May 2012. No one has been prosecuted for these attacks.

Artistic Freedom

As the authorities of the country try to increase its electoral support among more conservative layers of society, they rely more on support of the Russian Orthodox Church. Increasingly close political relationships between the state and the church account for much of the persecution of artists and censorship of arts on grounds of “protecting of traditional values”. One of the recent draft laws, adopted by the parliament in the first reading, provides for five years in prison for “insulting believers’ feelings”. Reports talk about increasing self-censorship among artists; several cases of prosecution were noted as well.

In August 2012 Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Maria Alekhina, and Ekaterina Samutsevich, members of punk group Pussy Riot, were each sentenced to two years imprisonment for organising a “punk prayer” in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow. Despite the group claiming their performance was an artistic act of political protest against President Putin’s regime, they were found guilty of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred.” In October 2012, Samutsevich was released on probation, but sentences against the other two members of the band were upheld.

Anti-extremist laws and articles of the Criminal Code relating to incitement to religious hatred have long been used for censorship of art in Russia. In July 2010 art curators Andrei Erofeev and Yuri Samodurov were fined for organising the Forbidden Art 2006 exhibition in Moscow, after several of the works were claimed by prosecutors to “incite hatred” and “denigrate human dignity.” In December 2012, prosecutors in St Petersburg launched an investigation into an exhibition by British artists Jake and Dinos Chapman after visitors complained it was “blasphemous” and “extremist” for featuring images of a crucified Ronald McDonald and Nazi symbolism.