Russian authorities have used the "foreign agents" law to limit advocacy, advisory, and public education outreach work by independent groups on a wide spectrum of issues that involve comment on or interaction with government authorities, Human Rights Watch said.

Russia’s Constitutional Court has upheld the controversial “foreign agents” law, Human Rights Watch said today. The law has been the centerpiece of the government’s near two-year crackdown on independent groups.

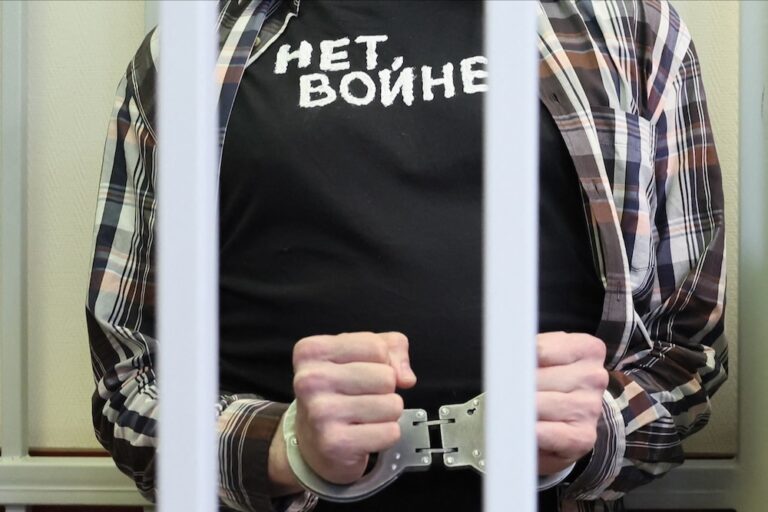

The law, adopted in July 2012, requires nongovernmental organizations that accept foreign funding and engage in “political activity” to register as “foreign agents,” a term generally understood in Russia to mean “traitor” or “spy.”

“The court’s ruling is deeply disappointing,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The “foreign agents” law violates fundamental rights and is designed to silence independent groups through intimidation and humiliation.”

The court ruled that there were no legal or constitutional grounds for contending that the term “foreign agent” had negative connotations from the Soviet era and that, therefore, its use was “not intended to persecute or discredit” groups. The court also found that the “foreign agent” designation was in the public interest and the interest of state sovereignty.

It said that groups that engage in political activity – actions “aimed at influencing state policy or related public opinion” – also “affect the rights and freedoms of all citizens,” and that if such groups accept foreign funding, “it cannot be excluded that they would use [the funds] in the interests of the sponsor.”

“It is distressing that the court made no distinction between advocacy that is [in] the public interest and partisan political activity,” Williamson said.

Equating groups that accept foreign funding with those that might represent the interests of a sponsor places an unjustified burden on a broad range of groups and presumes that such groups do not act on their own interests, Human Rights Watch said.

The court did clarify that a group could not be branded a “foreign agent” as a consequence of actions taken by its individual members in their private capacity. It also clarified that groups that criticize the authorities without intent to carry out “political activities” should not be considered “foreign agents.”

The ruling is final and cannot be appealed.

The Kostroma Center for Public Initiatives Support and Russia’s federal ombudsman, acting on behalf of four organizations and their leaders, filed petitions with the court in August 2013 to challenge the law. Three other groups also filed separate petitions.

Russian authorities have used the “foreign agents” law to limit advocacy, advisory, and public education outreach work by independent groups on a wide spectrum of issues that involve comment on or interaction with government authorities, Human Rights Watch said.

In March 2013 the prosecutor’s office began an unprecedented nationwide campaign of inspections of the offices of nongovernmental groups, and the authorities later targeted at least 90 groups in connection with the law. The prosecutor’s office and the Justice Ministry filed nine administrative cases against groups and an additional five administrative cases against group leaders for failure to register under the “foreign agents” law.

Several dozen groups received either notices from the prosecutor’s office that they were violating the law or warnings that they could be in violation. The Justice Ministry ordered two groups to suspend their activities for several months. At least four groups initiated proceedings on their own to wind up operations in order to avoid further repressive legal action.

Dozens of groups went to court to challenge the fines, warnings, and notifications they had received, and a number of these hearings are ongoing. In several cases the court hearings were postponed pending the Constitutional Court decision.

“We found that the authorities took advantage of the vagueness of the term ‘political activity’ or didn’t know how to interpret it,” Williamson said. “They targeted a very broad range of groups.”

On March 27 the chair of the upper chamber of parliament’s committee on constitutional law, Andrei Klishas, said that the upper chamber was working on amendments that would authorize the Justice Ministry to register groups as “foreign agents” without their consent.

“With new proposals to make the ‘foreign agents’ law even harsher, we had hoped for a ruling that would correct this deeply flawed law,” Williamson said.

Russian and intergovernmental human rights bodies have criticized the “foreign agents” law, finding that it contradicts Russia’s obligations to respect freedom of association and expression. In May 2013 the Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights criticized “the stark legal vagueness” of the term “political activities” and recommended that the law be amended to eliminate the very concept of a “foreign agent” organization.

In a friend of the court opinion prepared for the Constitutional Court, which Human Rights Watch has reviewed, the council said that “considering as ‘political’ activity aimed at shaping public opinion, disseminating one’s views, promoting the principles of the rule of law and the priority of human rights, criticizing the actions of law enforcement and other authorities leading to human rights violations, and imposing on this basis additional encumbrances constitutes a violation of the freedom of expression.”

In April 2013 Nils Muiznieks, the Council of Europe commissioner for human rights, similarly criticized the law, saying that “being labelled as a ‘foreign agent’ signifies that an NGO would not be able to function properly, since other people and – in particular – representatives of the state institutions will certainly be reluctant to co-operate with them, in particular in discussions on possible changes to legislation or public policy.”

The Council of Europe’s Venice Commission, an advisory body on constitutional matters, is currently reviewing the “foreign agents” law.

In September 2013 the Venice Commission and the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe issued a joint opinion on a draft “foreign agents” bill proposed by the Kyrgyz parliament that is very similar to its Russian counterpart.

The joint opinion said that the bill gave the authorities “overly broad discretion in labeling an activity as ‘political.’” It also said that the authorities would be “more likely to impose [the ‘foreign agent’ label] on those associations whose members do not share the political views of the ruling authorities,” which “would result in associations being penalized on account of their political convictions, which amounts to discrimination prohibited under international standards.”

The opinion further noted that the overly broad definition of political activities would cover “not only those organizations which are de facto involved in lobbying or partisan political activities, but virtually all NGOs carrying out any form of legitimate public advocacy.” It recommended that a line be drawn “between advocacy, on the one hand, and partisan political activity on the other” and that “[i]ndividuals and non-commercial organizations should not be precluded from advocacy work on issues of public concern, regardless of whether or not their position is in accord with governmental policy.”

The joint opinion is not automatically applicable to the Russian law but indicative of what the Venice Commission would conclude on a similar law.

Thirteen leading rights groups have filed a case over the “foreign agents” law with the European Court of Human Rights.