A Russian court has ruled that the Center for Social Policy and Gender Studies (CSPGS), an independent group in Saratov that does research on social issues, must register as a "foreign agent" organization. It is the first time a court has required any independent group to register under Russia's "foreign agents" law.

A Russian court has ruled that a research organization must register as a “foreign agent” organization, Human Rights Watch said today. It is the first time a court has required any independent group to register under the “foreign agents” law adopted by Russia’s parliament in 2012.

On November 27, 2013, the Kirovsky District Court in Saratov, 725 kilometers southeast of Moscow, ruled in a civil suit brought by a local prosecutor’s office against the Center for Social Policy and Gender Studies (CSPGS), an independent group in Saratov that does research on social issues. Similar civil lawsuits brought by prosecutors’ offices elsewhere in Russia against three other groups are pending in the courts.

“The court’s ruling in Saratov sets a dangerous precedent,” said Tanya Lokshina, Russia program director at Human Rights Watch. “Forcing a research organization to register as a ‘foreign agent’ casts an ominous shadow over every independent group in Russia.”

Amendments to Russia’s laws regulating nongovernmental organizations, adopted in July 2012, require any organization receiving foreign funding and engaging in “political activities” to register as a “foreign agent” and identify itself as such in all publications.

Russian prosecutors’ efforts to use administrative court proceedings to force six prominent Russian groups to register as “foreign agents” were rejected by the courts. Rather than accepting those rulings, the prosecutors opted for civil suits as a new tactic. Prosecutor’s offices have brought suits against at least three other groups – Anti-Discrimination Сenter Memorial and Coming Out, both in St. Petersburg, and Women of the Don in Novocherkassk.

Russia’s civil procedure code allows the prosecutors’ offices to file civil suits to protect the rights, freedoms, and lawful interests of, among others, “undefined groups of persons or interests of the Russian Federation.”

The Oktyabrsky district prosecutor’s office in Saratov, which had filed the civil suit in September, argued that because CSPGS receives foreign funding and is involved in “political activities,” as defined by the law, it was misleading the public by failing to register as a “foreign agent.” If the group exhausts appeals and the court ruling goes into effect, the organization will have two weeks to register as a “foreign agent” organization.

If it fails to do so, the head of the organization could risk criminal prosecution under the terms of the “foreign agents” law, and if convicted, sentenced to up to two years’ imprisonment. The group told Human Rights Watch it will appeal the ruling.

CSPGS researches contemporary social problems – including governmental social policies – issues analytical publications, and organizes academic discussions. In its civil complaint, the prosecutor’s office cited several activities by the group that were deemed “political,” including a seminar the group organized entitled, “Review of Social Policy in the Post-Soviet Era: Ideologies, Actors, and Cultures” and an April 2013 publication by the group, Critical Analysis of the Social Policy in the Countries of Former Soviet Union.

The complaint quoted an expert assessment by a Saratov State Legal Academy professor that stated, “In a transitional society any issue could become political… if it concerns a large number of people, and social policy is no exception.”

“The evidence cited by the prosecutor’s office and upheld by the court confirms some of our worst fears that the authorities would define ‘political’ so broadly that it could include just about any activity,” Lokshina said.

The prosecutor also cited a petition campaign that several activists started to protect the group from the “foreign agents” law. Prosecutors contended that a public statement made by Dutch activists in support of the group demonstrated that, “[t]he organization’s foreign colleagues view it as an organization that participates in the country’s public and political life and influences the development of democratic processes in the country, in other words, as political.”

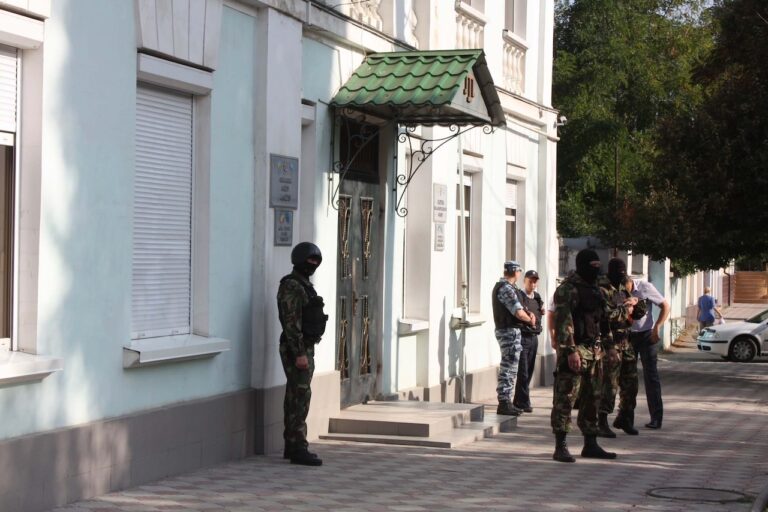

In April, at the peak of the nationwide governmental inspection campaign aimed at identifying “foreign agent” organizations, prosecutors and tax officials inspected CSPGS. On April 24, the organization received a “notice of violations” from the prosecutor’s office ordering it to register as a “foreign agent” group. On June 25, the group filed a written objection with the prosecutor’s office, saying it did not carry out political activities. On September 10, the prosecutor’s office filed the civil suit.

The organization’s deputy director, Natalia Lovtsova, told Human Rights Watch that in May the local anti-extremism police department summoned her for an interview. The officers indicated that they were running a preliminary check of the group’s possible involvement in “extremism and terrorism.” She said the officers gave her a list of names asking her if she recognized any of those people as “spies.” The list included names of some participants in the group’s academic conferences and other events. Lovtsova told Human Rights Watch that she told the officers that she had no idea why those individuals would be suspected of espionage.

The “foreign agents” law contradicts Russia’s international human rights obligations to protect freedom of association and expression. Russia’s international partners should join forces in urging the Kremlin to stop the crackdown against independent groups, Human Rights Watch said.

“The ‘foreign agents’ law is one of many tools the authorities are using to tar independent groups as ‘spies,’” Lokshina said. “The authorities’ efforts to demonize critics of the government are reminiscent of the cold war.”