Since Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency in May 2012, Russia has seen a flurry of restrictive new regulations regarding online freedom of expression, resulting in a score decline for the country in the latest edition of Freedom on the Net, Freedom House’s annual report on online and digital media freedoms.

By Laura Reed, Research Analyst, Freedom on the Net

Since Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency in May 2012, Russia has seen a flurry of restrictive new regulations regarding online freedom of expression, resulting in a score decline for the country in the latest edition of Freedom on the Net, Freedom House’s annual report on online and digital media freedoms. However, even greater deterioration is likely in the coming year as the government continues to enact repressive laws and ramps up its surveillance capabilities ahead of the 2014 Winter Olympics in the southern city of Sochi.

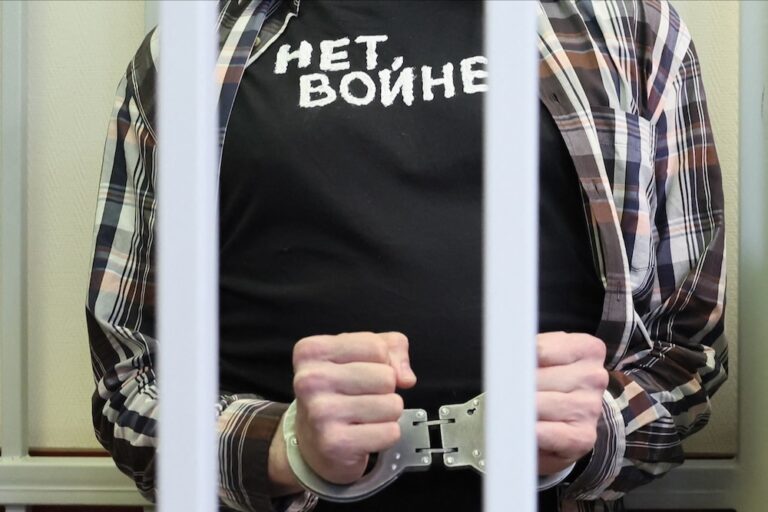

Over the past year, Russia has taken a number of legislative and judicial steps to regulate online content. In July 2012, the State Duma passed a law that recriminalized defamation for both online and offline media, and in the same month passed a law that allows the telecommunications regulatory authority and other government agencies to add domain names and IP addresses to a “blacklist” of websites that internet service providers (ISPs) must block. Most significantly, government agencies are not required to obtain a court order before blocking websites. The past year has also featured increases in requests from local prosecutors to block online content and a rise in the number of prosecutions of internet users, which jumped from 31 cases in 2011 to 103 cases in 2012.

Since April 2013, the end of the period covered by the latest Freedom on the Net report, the Kremlin has only accelerated its efforts to control the online sphere. Perhaps most worrying are recent revelations about the extent of surveillance of online and mobile communications within Russia, the export of these technologies to other authoritarian countries in the region, and the actions Russia is taking to bolster its surveillance capabilities ahead of the Winter Games.

Russia’s key eavesdropping technology, known as the “system of operative-investigative measures” (SORM), allows security agencies to directly access electronic communications infrastructure through surveillance “black boxes,” which all service providers are obliged to install at their own expense. Security service officers are required by law to obtain a court order before intercepting phone calls or e-mail messages, but they are not required to show the warrant to anyone other than their supervisors, and service providers cannot demand to see the warrant.

According to a recent report, such methods are not confined to Russia. The SORM technology pioneered by Moscow has been adopted in Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan, and some of these former Soviet states continue to update their infrastructure with Russian technological advances. Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan have also reportedly purchased Russian surveillance technology such as “the Semantic Archive”—software that monitors open data sources, such as social networks and blogs, for keywords, and then analyzes this data to chart connections between users.

Meanwhile, records of government procurement documents show that Russia is upgrading its domestic surveillance infrastructure, allowing the government to extensively monitor and filter all communications during the Olympic Games. Observers have raised concerns about the possible impact on athletes and visitors who comment on or protest against Russia’s discriminatory ban on “homosexual propaganda,” which is widely condemned by the international human rights community and has drawn significant attention to the broader human rights situation in Russia.

Given the marked increase in surveillance efforts, restrictive legislation, and prosecutions of individuals for content posted online, the threat that Russia poses to online and digital media freedom should not be overlooked. Moscow remains a strong player in the region, with many former Soviet states following its lead, often with negative consequences for human rights and democratic institutions. Moreover, the most important print and broadcast media in these countries have long been dominated by the state and its private-sector allies, leaving the internet as one of the last relatively open venues for the exchange of uncensored news and information. Unless there is substantial pushback from the international community in response to the Russian government’s actions, citizens from Eastern Europe to Central Asia may soon suffer a dramatic reduction in their ability to communicate freely in any medium.