The 7-year jail sentence and 4,280 Euro fine slapped on YouTuber Dieudonné Niyonsenga by Rwanda's High Court has been described as 'absurd" by RSF.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 22 November 2021.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) condemns the absurd and arbitrary seven-year prison sentence that Dieudonné Niyonsenga, the operator of an online TV channel called Ishema TV, has received from Rwanda’s high court as a result of an appeal by the prosecutor’s office against his acquittal at his initial trial. The authorities must stop persecuting online journalists, RSF says.

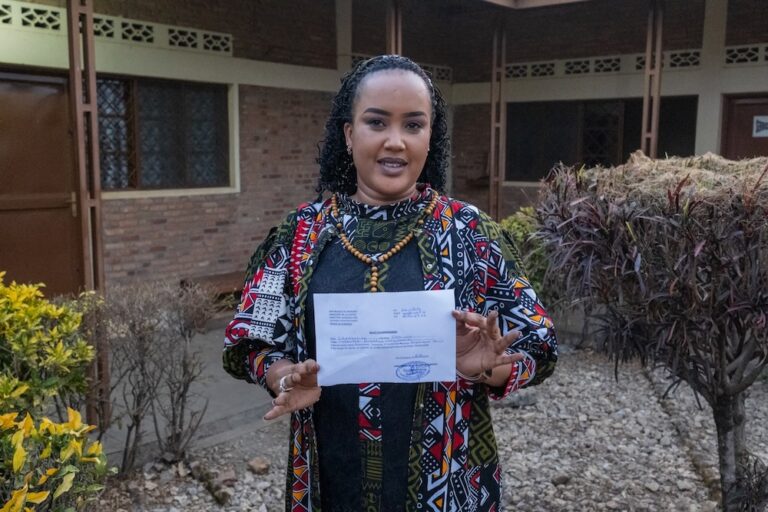

Also known as Cyuma Hassan, Niyonsenga had enjoyed eight months of freedom after his initial acquittal before being returned to prison following the high court’s decision on 11 November to convict him on charges of assault, obstructing police officers and practicing journalism without a press card.

Niyonsenga’s problems date back to 15 April 2020, when he was arrested while on his way to cover the impact of the government’s coronavirus lockdown, and was charged with contravening the lockdown and showing false press cards to the police.

After 11 months in pre-trial detention, during which it was almost impossible for his family or his lawyer to contact him, his ordeal seemed to be over on 14 April, when he was released two days after his initial acquittal. But, following last week’s high court decision to sentence him to seven years in prison and a fine of 5 million Rwandan francs (4,280 euros) on appeal, he was returned to Magerarege prison, the country’s biggest detention centre. His lawyer told RSF he intends to appeal against the decision.

“After nearly a year of pre-trial detention, this very heavy and utterly arbitrary sentence is absurd,” said Arnaud Froger. the head of RSF’s Africa desk. “It is now clear that the charges brought against this journalist were just a cover for what was the real problem for the Rwandan authorities – his news coverage, his investigative reporting and the critical line taken by his online TV channel. We call on the authorities to release him and to stop arresting and jailing journalists arbitrarily, including online journalists.”

Niyonsenga is known for his coverage of disadvantaged neighbourhoods. A few weeks before his initial arrest, he had posted videos, including interviews, about alleged cases of rape and looting by soldiers. He had also published reports about the authorities destroying homes at the height of the pandemic. And in February 2020, he reported seeing injuries on the face of Kizito Mihigo at this famous singer and peace activist’s funeral, thereby challenging the government’s version that Mihigo took his own life.

The authorities meanwhile arrested Theoneste Nsengimana, the director of Umubavu TV, a YouTube TV channel critical of the government, on 13 October for posting a video that was deemed to have spread “rumours designed to trigger an uprising.”

He is currently being held in Magerarege prison on charges of membership of a criminal group, disseminating propaganda designed to damage the government’s image abroad, and spreading rumours constituting incitement and agitation. His lawyer has filed a petition for his release at the next hearing and describes his detention as “completely illegal and a violation of freedom of expression.” Previously arrested in April 2020 on a charge of gathering false statements, Nsengimana was released a month later for lack of evidence.

The Rwanda Investigation Bureau (RIB), the agency responsible for investigating technological crime, meanwhile began talks with Google earlier this month with the aim of closing down YouTube channels carrying videos with “words for expressions that constitute crimes.”

In a statement issued on 13 April, the Rwanda Media Commission said that personal YouTube channel operators would not be accorded the status of journalists. But the Rwandan code of media ethics and conduct is currently being revised with the aim of incorporating social media into the definition of professional journalism.

Rwanda is ranked 156th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2021 World Press Freedom Index.