In December, eighteen U.S. lawmakers demanded that the U.S. government impose sanctions on four non-US surveillance companies for, as they mention in their letter, facilitating “disappearance, torture and murder of human rights activists and journalists”.

This statement was originally published on privacyinternational.org on 15 December 2021.

Following recent moves to use export controls to reign in surveillance companies, members of Congress are demanding that the U.S. government now also impose sanctions. PI answers some questions and looks at the potential impact.

Following sustained reporting by researchers, journalists and activists around the world, including recent disclosures exposed by the PegasusProject, the surveillance industry is facing scrutiny like never before.

In the latest move, eighteen U.S. lawmakers have today demanded that the U.S. government impose sanctions on four non-US surveillance companies for, as they mention in their letter, facilitating “disappearance, torture and murder of human rights activists and journalists”.

The move follows recent steps taken by the U.S. government to use export control restrictions to restrict trade with specific companies and to call on counterparts to “prevent the proliferation of software and other technologies used to enable serious human rights abuses.”

But while such scrutiny and regulation is hugely welcome, they will only be effective if authorities take their responsibilities seriously and as part of a broader, multi-pronged solution.

What is the Global Magnitsky Sanctions Act and what will be its impact?

Signed in 2016, the Global Magnitsky Act authorizes the U.S. government to sanction those it sees as human rights offenders, freeze their assets, and ban them from entering the U.S. The Act applies globally to both individuals and companies.

Congress is calling on the Act to be used to sanction four surveillance companies:

- NSO Group, Israel: Primarily known for its proprietary spyware Pegasus, which is capable of remote zero-click surveillance of smartphones.

- Trovicor, Germany: Known for its sale of network-based interception products, previously subject of an OECD complaint by Privacy International and partners.

- DarkMatter, UAE: Selling a complete portfolio of cyber security solutions and reported to have, some of which have reportedly been used to hack human rights activists.

- Nexa Technologies, France: Recently exposed to have supplied internet surveillance to Egypt and elsewhere, and subject of a judicial investigation for “complicity in acts of torture and enforced disappearance” in Libya and Egypt.

If passed, essentially all of the property and interests in property within US jurisdiction of the designated individuals and entities can be blocked, and U.S. persons are generally prohibited from engaging in transactions with them. Further, it will block the companies out of the U.S. financial system, for example restricting U.S. investors from investing in them.

How does it differ from previous “blacklisting”?

The call follows a move last month by the Commerce Department to place four companies on its “Entity List”, including NSO Group. The US Entity List bars U.S entities from exporting goods and services, which require export permission, to these companies unless they receive explicit permission and for which there is a presumption of denial.

The Entity List is a tool used to restrict the export, reexport, and in-country transfer of items subject to the Exports Administration Regulations (EAR) to persons. As such, the listing is not as far-reaching as being sanctioned because it is only focused on items that are already listed in the EAR.

Individuals, organizations, and companies reasonably believed to be involved, have been involved, or pose a significant risk of being or becoming involved, in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the U.S. can be placed on the list.

As we understand this, it essentially restricts the ability of U.S. companies to provide services and products to such companies, given that permission is subject to a presumption of denial. Although in NSO Group’s case it is based in Israel and it is arguable that it could in theory run its operation without any controlled supplies from U.S. entities, it also sends a strong message to its potential customers and other governments. Israeli authorities, for example, have since announced that they will tighten exports of surveillance technology, though it remains to be seen if this will be the case.

What else has the US announced?

Following this month’s US-led “Summit for Democracy”, the US has also announced a Code of Conduct which seeks to restrict exports of surveillance technology. Signed together with the governments of Australia, Denmark, and Norway – and supported by Canada, France, the Netherlands, and the UK – the code will seek to “use export control tools to prevent the proliferation of software and other technologies used to enable serious human rights abuses”.

However, as a non-binding and voluntary code, the impact this will have on these countries’ export decisions remains uncertain, especially given that many of these countries have continued to export surveillance technology despite already having human rights criteria in place. However, it probably remains the highest-level political recognition of the need to take steps to date.

Has the US imposed sanctions to other companies?

Since it came into effect, there are already other companies included in the list affiliated with persons that have been considered to be involved in serious violations of human rights.

What other similar movements have been?

Earlier this year, after years of campaigning by Privacy International and civil society partners around the world, the EU implemented changes to its export control regulations with the aim of better controlling exports of surveillance technology. While the changes do not go as far as they could have, they present a major opportunity for EU countries to take the lead in controlling the trade, and will – for the first time – provide transparency into the EU trade.

The EU also has a similar law which allows it to impose sanctions over serious violations of human rights targeting governments of non-EU countries, as well as companies, groups, organisations, or individuals. It can impose arms embargoes, asset freezes, and other economic measures such as restrictions on imports and exports.

On 3 December 2021, together with a group of other civil society actors, we submitted a letter urging the EU to take serious and effective measures against NSO Group, including the designation of the entity under the EU’s global human rights sanctions regime. 82 groups and 6 individuals signed the letter.

Among others, Canada, the UK, and Australia have similar legal regimes that would allow them to impose sanctions.

Calling for a human rights approach to surveillance

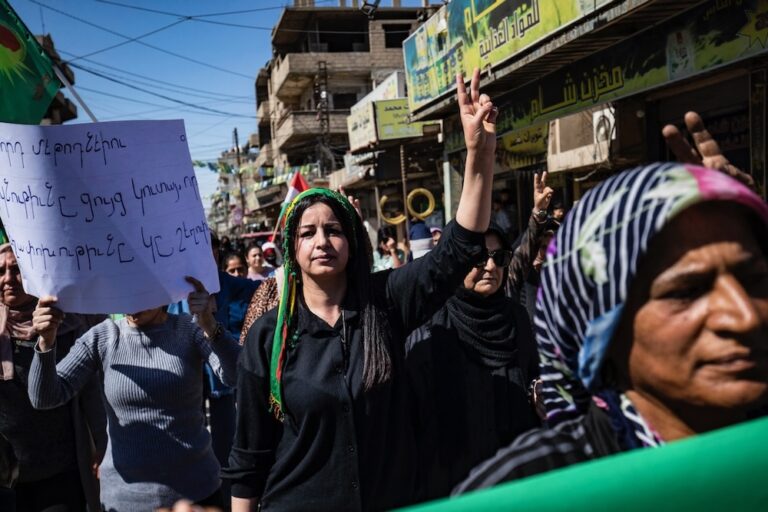

Surveillance technologies are radically transforming the ability of authorities to monitor civic spaces that see the space around them increasingly shrinking. Across the world right now, governments are cracking down on dissent and preventing human rights defenders, activists, journalists, and lawyers from carrying out their work. They are threatened and attacked using a range of tactics, including government hacking.

Due to the unique and grave threats presented to privacy and security, Privacy International believes that even where governments conduct surveillance in connection with legitimate activities, such as gathering evidence in a criminal investigation, they may never be able to demonstrate that hacking as a form of surveillance is compatible with international human rights law.

As governments still resort to such hacking powers, though, PI has been advocating for a human rights approach to surveillance. For this reason, we developed a series of necessary safeguards designed to assess government hacking in light of applicable international human rights law. They are further designed to address the security implications of government hacking.

In brief, the law enabling these surveillance powers must be accessible to the public and be sufficiently clear and precise to enable persons to foresee its application and the extent of the interference with their rights. It should also be subject to periodic review by means of a participatory legislative process.