A decade ago, the term "citizen journalism" was nearly as mainstream as mainstream news itself. But what does it mean today?

This statement was originally published on wan-ifra.org on 27 November 2017.

By Colette Davidson

In July 2016, elementary school worker Philando Castile’s shooting death by a Minnesota police officer captivated the United States. His girlfriend Diamond Reynolds had pulled out her cell phone at the time of Castile’s death, filming the scene and live blogging it on Facebook. While there were aspects of his death that remained contentious, much of what happened was available for the world to see.

Reynolds probably didn’t consider herself a citizen journalist at the time, but she – and so many others around the globe – are using their cell phones to record daily events and broadcast them across social media. They’re going where mainstream journalists can’t go, where authorities aren’t, and they’re providing information that isn’t available anywhere else. Citizen journalists are changing the news media landscape of today – only many wouldn’t call themselves as such.

Dr Saqib Riaz, an associate professor of mass communication at Allama Iqbal Open University in Islamabad, Pakistan, says the title has changed but the phenomenon is still the same.

“Now, social media has taken the job of citizen journalism,” he says. “Basically, social media is an advanced form of citizen journalism that has made it possible for each and every person to be a citizen journalist, upload still and moving images, photographs, videos, audios, comments and many other things.”

Less than a decade ago, social media was just starting to find its footing. When smart phone technology exploded around the world in 2013, recording daily events and uploading content via social media became commonplace. And that threatened – and continues to threaten – how professional journalists do their jobs. As it is physically impossible for journalists to be present at every event, social movement or crime scene in the world, people rely heavily on this new form of citizen journalism.

“When things happen or there’s breaking news, we expect citizens to be there and to be the first ones on the scene,” says Stuart Allan, Professor and Head of the School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies at Cardiff University.

But Allan says that while experts may call the phenomenon citizen journalism, not all citizens may be aware that they’re taking part in creating the news.

“There are plenty of people who go to the scene, document it with a cell phone and upload it to social media but don’t consider themselves journalists,” says Allan. “And then there are some people who have a desk job during the day and at night will go to cover a local meeting at night now that their local paper doesn’t exist.”

In the same way citizen journalism functioned years ago as a way for little-known news to get reported, the current social media documentation of events offers a way for people to get news about anything and everything. And the mainstream media – while it has mixed feelings about the role of social media in capturing the news – relies heavily on this information.

“Many untold and unreported news stories appear every day on social media and traditional media picks them up and publishes or broadcasts them,” says Dr. Riaz. “If you see something happening before you, you can simply record it on your phone and share it on social media. This is the simple philosophy and strength of today’s citizen journalism.”

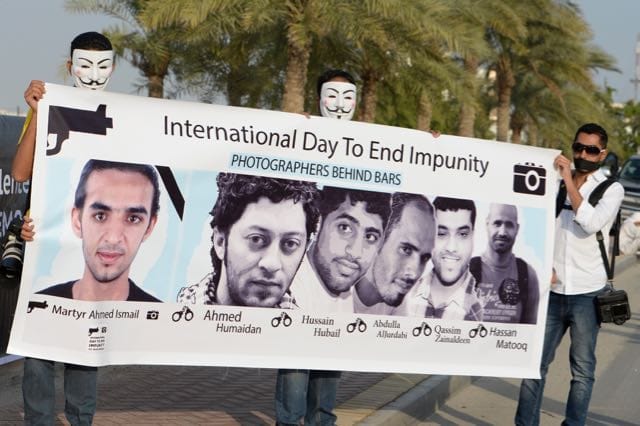

Social media can also go where mainstream media won’t go, due to safety concerns. Citizen journalists have been vital to getting news from Syria since its seven-year-long civil war began. Most mainstream media outlets in the West have been unwilling to send journalists to Yemen to report on the on-going crisis, due to fears for their safety. And in the tribal areas of Pakistan, where the country’s 2,000-kilometer border with Afghanistan has become a war zone in the last two decades, social media has played an essential role in the war against terrorism.

“It was only citizen journalism that captured many terrorism-related activities and later on, this news was picked up by the international media,” says Dr. Riaz.

But while the international media often welcomes content from citizen journalists, there are times when it seems to hinder professional reporting. The ease with which citizens can upload content online makes it infinitely impossible to verify sources and information, and has given rise to an onslaught of fake news.

US President Donald Trump’s use of Twitter to broadcast information has been impulsive at best, with numerous instances of nefarious or dubious information gracing his social media account – only to later become fodder for mainstream news articles.

Sifting through what is true or not has made traditional media – and their ability to independently verify information indelibly more important. Even amidst the social media storm – and often thanks to it – news outlets are using tried and true techniques to check information uploaded online before republishing it. Dr. Allan says that media houses can verify images by taking them apart or use methods to check whether a person was where they claimed to be.

“The NY Times will say Trump is the best thing to have happened for its subscription rate,” says Allan. “People are starting to see that they have to pay for good quality reporting.”

While the future of the news and how it is defined is constantly in flux, citizen journalism – and social media – appears to be here to stay. But, according to Allan, there’s nothing necessarily wrong with that. He says that while the media needs to have a serious conversation about what good reporting is and how to maintain professional integrity, citizen journalism is “real” news that can certainly enter into the fore.

“In journalism, there’s plenty of room for a healthy, vibrant debate that includes as many people as possible,” says Allan. “It just makes it more of a challenge.”