Security is a factor in Burkina Faso's election, with implications for disenfranchised voters and media safety, as is the uneven allocation of airtime to certain candidates.

This statement was originally published on mfwa.org on 21 November 2020.

On Sunday November 22, 2020, Burkinabés will be going to the polls in presidential and legislative elections. This will be the country’s second elections since a popular uprising in 2014 toppled its long-standing dictator Blaise Compaoré. The highly anticipated election comes as the country is engulfed in the fight against terrorism and its attendant spiralling insecurity.

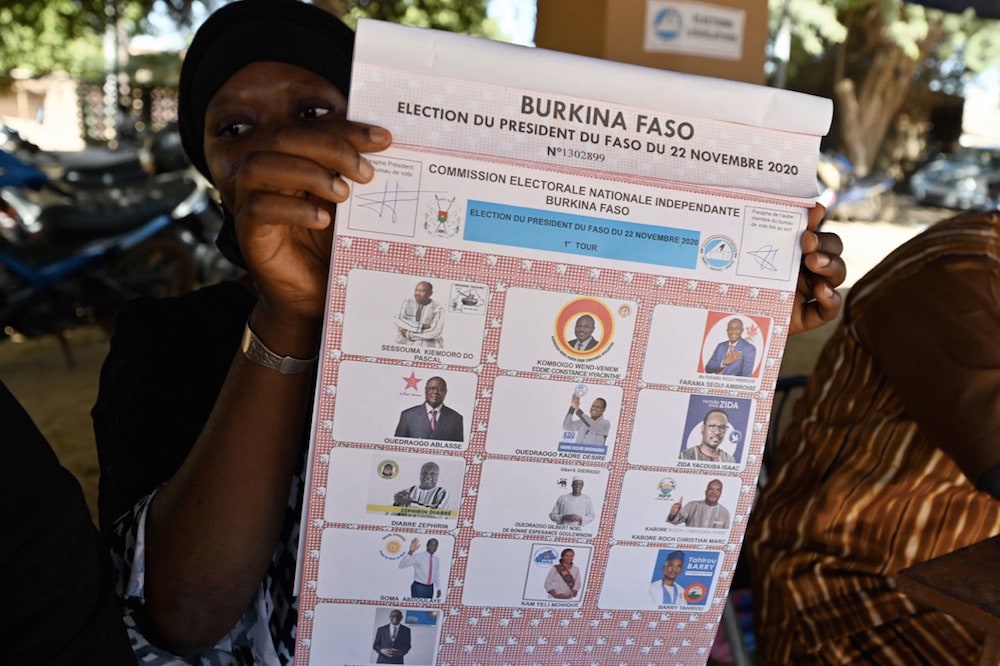

Among the thirteen (13) presidential candidates are the incumbent Roch Christian Marc Kaboré from Movement du Peuple pour le Progress (MPP), Zephirin Diabré from the Union for Progress and Change (UPC), Burkina Faso’s main opposition party, and Eddie Komboego from the Congress for Democracy and Progress (CDP) former dictator Blaise Compaoré political party.

Top of the issues defining this year’s elections is how to put an end to the series of terrorist attacks which have already claimed thousands of lives. Electoral campaigns by party candidates, political debates and media current affairs programmes have been inundated with the quest for who can offer the most effective leadership in the country’s fight against terrorism. According to Younouss Ouédraogo, chief editor at the daily Bendré, in Ouagadougou “citizens are glued to their televisions and radio sets to see which of the candidate offers the best solution to put an end to the terrorism crisis and restore security”.

Ahead of the polls, the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA) carried out an analysis of the critical issues and their impact on the upcoming election.

Disenfranchisement of some citizens due to terrorism

Since 2015, the terrorism spill over in Burkina Faso from neighbouring Mali has triggered a series of deadly attacks claiming over 1,800 lives. The security context has considerably impacted the preparation of the elections. Ahead of the polls, the Independent Electoral Commission (CENI) declared it would be difficult to register new voters in regions prone to terrorist attacks and insecurity. In August, the Electoral Commission declared that 22 of the 351 districts of the country were not covered by the voters’ registration exercise, leaving out roughly about 417,465 potential voters in about 1,645 villages. The regions affected are the Sahel, the Eastern, the Centre North, and Boucle du Mouhoun regions that are currently overrun by terrorist groups.

Considering the security crisis, the country’s Parliament on August 25, 2020, adopted a new law which modifies the electoral code and introduces a new “force majeur” clause. According to the new law, the presidential and legislative election would be considered as valid and credible even if citizens in some regions are unable to vote in case of unforeseen circumstances. Following the adoption of the new electoral law, the constitutional council declared 17.70% of the country will not be covered by the election due to the level of insecurity, and stopped all electoral processes in these areas.

Paul Mikir Roamba, Chief Editor at Ouaga FM, believes that key stakeholders are not surprised that citizens in parts of the country would not be able to vote. “It is a situation that many saw coming due to the level of insecurity witnessed in the country. However, Parliament could have consulted the population because citizens have a say in this process,” he said.

The media and public discourse

Burkina Faso is home to a burgeoning media landscape. Following the 2014 popular uprising, the country witnessed a sharp improvement in freedom of expression and of the press. The transitional parliament in 2015 adopted several laws to guarantee civil liberties including the Right to Information law resulting in an explosion of media organisations across the country. Today, the media landscape in Burkina Faso is made up of 87 newspapers; 25 registered online media, 163 radio stations; and 33 television channels.

The traditional or mainstream media has been active, reflecting the highly pluralistic nature of the country’s media landscape. There has been an increased coverage of the electoral processes and topical issues on politics and propositions by the various candidates.

Throughout the campaign season, the state-owned media has organised a series of debates on the policy propositions of candidates. Furthermore, the media provided to each presidential candidate a platform to inform the electorate of their manifestos. Media organisations have also allocated airtime to the Electoral Commission to inform the citizenry of the preparation for the upcoming polls.

Considering that media organisations are very active ahead of the polls, the High Council of Communication (CSC) carried out a monitoring exercise to find out if media outlets are complying with the election coverage guide. Although the report recorded that media organisations are largely abiding by the ethical code, the CSC underscored instances of uneven allocation of airtime by mainstream media. The CSC underlined the incumbent had more coverage on state-owned media than other candidates. This situation has also been recorded on private media, especially on outlets such as 3TV, BF1, Burkina Info, and Canal3.

The uneven allocation of airtime is mainly due to the struggle for survival of media organisations who offer more airtime to candidates who are able to afford it.

Younouss Ouédraogo, chief editor at the daily bendré, underlined that “in Burkina Faso, media outlets are, to a certain extent, neutral. However, during the campaign, coverage preference is given to candidates who are able to afford more airtime. And so, many of those candidates are even covered live on mainstream media during some of their rallies”.

Diaspora voting and the influence of social media and fake news

This year and for the first time in the history of Burkina Faso, citizens in the diaspora will vote. Increasingly, social media has become a battleground for candidates wishing to win more votes. Candidates have adopted a social media strategy. Most of the candidates have a Twitter, a Facebook, or even an Instagram account through which they communicate with the population, including the diaspora.

In the wake of the campaign, the media landscape saw the multiplication of Web TVs, and the massive use of the live option on platforms such as Facebook, especially by candidates who were unable to travel to other countries to campaign.

Following the incidence of the COVID-19 pandemic which saw a spike in the use of online working platforms, Burkinabés from the diaspora introduced in the political arena the use of platforms such as Zoom, where they organise on a regular basis webinars and online conferences with candidates to hear about their projects and plans for the country.

Media safety during the election

Considering the high level of insecurity in Burkina Faso, media professionals have often expressed the need for security. Over the years, reporters have often been threatened by terrorists for denouncing their actions. Media organisations in territories overrun by armed groups have usually had to relocate to save their lives.

This year, and for the first time in the history of Burkina Faso, ahead of the polls, issues of media safety during the elections have been considered by the electoral commission.

The High Council of Communication, and the Electoral Commission in collaboration with security agencies across the country organised training programmes for the media. The trainings focused on providing media professionals security tips on how they could ensure their safety.

Both the Electoral Commission and the Council of Communication have also sensitised security officers on the imperative to protect both candidates and reporters during the election in case of any danger.

As the polls draw nearer the Media Foundation for West Africa wishes to commend the key stakeholders for actions taken so far to ensure a clean campaign and the protection of journalists. We urge the political actors to continue to exhibit tolerance and maturity during and after the election, in order to reclaim for the ECOWAS region some of the lost political grounds following recent controversial elections in Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea.