By placing technology-facilitated gender-based violence on centre stage, a Resolution on the Protection of Women Against Digital Violence in Africa could be instrumental in ensuring human rights principles are safeguarded in the online domain.

IFEX Africa Regional Editor Reyhana Masters spoke with advocates across the African continent to get their perspectives on the effectiveness of this instrument in curbing online harm, while deliberating on its potential impact and recommending areas for improvement.

Advocates interviewed for this piece:

- Sandra Aceng – Executive Director, Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET)

- Patricia Ainembabazi – Project Officer, Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA)

- Hlengiwe Dube – Project Manager for Expression, Information and Digital Rights Unit, Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria

- Dr. Tabani Moyo – Regional Secretariat Director, Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA)

- Zoe Titus – Executive Director, NMT Media Foundation

- Edrine Wanyama – Legal Officer, Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA)

Offsetting virtual violence

In a previous brief, I explored the potential of ACHPR Resolution 522 to address technology-facilitated gender-based violence. In this update, I dig a little more into its impact, engaging with stakeholders to examine how it has been utilised. I wanted to get a better understanding of how the recommendations put forward in this resolution have been implemented and how this contributes to curbing the proliferation of digital violence against women.

Over the years, the weaponisation of the online sphere to harass, intimidate, discriminate, threaten, and violate women, as well as other marginalised users, has deepened, and its intended impact of shutting out critical voices is being widely felt.

Examples abound.

Thousands of women in Ethiopia have had their lives upended by threats of their intimate photos being shared without their consent. What may have started out as a personal vendetta by a former partner has morphed into a more insidious and organised industry, as women’s private moments are turned into profit through social media platforms. Research by the Centre for Information Resilience (CIR) reveals that this online abuse against women in Ethiopia has become so normalised that it often goes unnoticed. In this conservative society the women are shamed into silence and forced to retreat from public spaces, thereby curtailing their participation in public life.

Mozambican human rights defender Fatima Mbire had to contend with a targeted smear campaign and death threats on Facebook following revelations of illicit government expenditure.

In a nuanced tweet above her picture, a political commentator intimated that the Zimbabwean Minister for Information and Communication Technology, Tatenda Mavetera, had secured her appointment as a result of an intimate relationship.

Award-winning South African editor and journalist Ferial Haffajee described how indecent and offensive images of her flooded social media platforms. “I was photoshopped on to a barely clothed dancer; then I was a busty cheerleader wearing a barely-there costume; then I was a dog being walked by Rupert and a cow being milked by him. A dog, a cow, a prostitute — the nasty purveyors of online hate could not get more stereotypically sexist.”

Ugandan lawyer and public administrator Jennifer Semakula Musisi, who served as the first executive director of the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA), had to wrestle with social media users as well as the media, for reducing her professional achievements through their objectification of her. A blog ran a story about her resignation from the KCCA with the title “Hips, Swag, Pomp and the side of Jennifer Musisi you will definitely miss”, while a story about her participation in the Makerere University marathon was titled “Makerere Runners To View Jennifer Musisi’s Booty In HD”. She was also featured on a list titled “Battle of the buttocks: Who has the biggest pair in Uganda?”

This is particularly poignant, given how the advent of digital technologies first ignited such hope.

There was a promise that offline disparities would somehow be reduced, and there was expectation that digital inclusion would allow increased opportunities for women, girls, and other marginalised groups, while at the same time stripping down harmful gender norms and stereotypes.

As Louis Arimatsu points out in her paper “Silencing women in the digital age”, “[this] original euphoria was somewhat dampened by the realisation that . . . not only were ‘new technologies travel[ling] on old social relations’, but pre-existing disparities were being accentuated by digital technologies, further excluding already marginalised communities, including women.”

In a foreword to the NMT Media Foundation’s study examining the impact of online hate speech targeting the LGBTQI+ community in Namibia, executive director Zoe Titus points out that “despite their capacity to amplify marginalised voices, these platforms frequently fail to protect users adequately, allowing hate speech to proliferate.”

A study by DW Akademie observes how “this has a direct impact on women’s digital participation, as many survivors of various forms of online violence against women withdraw from online media and their voices fall silent.”

When this happens, civic space is profoundly impoverished. In a policy brief, researchers Shingirai Mtero, Mandiedza Parichi and Diana Højlund Madsen attribute the decrease of Zimbabwean women’s participation in politics in part to the rise in online attacks, alongside “financial obstacles and patriarchal attitudes.”

A framework for remedial recommendations

Adopted in 2022 by the African Union at its 71st Ordinary Summit in the Resolution on the Protection of Women Against Digital Violence in Africa, ACHPR/Res. 522 (LXXII) is a significant milestone, the first instrument agreed upon by a continental member state institution to specifically address technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV).

Its symbolism and importance is summed up by Dr. Tabani Moyo, director of the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) regional secretariat:

“As an advocacy mechanism rooted in African institutions, it is owned by the continent’s decision-makers and citizens. Unlike many human rights frameworks often dismissed by governments as Western constructs, this resolution is created by Africans for Africans. It stands as a testament to the progressive nature of African institutions and their evolution in addressing societal changes driven by environmental factors, including technology, culture, economy, and socio-legal and political dynamics.”

In Resolution 522’s two years of existence, it has already contributed to transformative changes in the approach to online harassment, intimidation, and discrimination of women on the African continent.

Advocates and activists agree that while there is need to increase awareness, there is broad acknowledgement that the resolution has promoted broader and more informed conversations about women’s safety online, reshaped advocacy initiatives, and strengthened strategic interventions around TFGBV.

Hlengiwe Dube, the project manager for expression, information, and digital rights unit at the Centre for Human Rights at the University of Pretoria, views Resolution 522 as a “pioneering step towards addressing the intersection of gender-based violence and the digital environment.” Dr. Moyo noted that it “has started the conversation and mainstreamed the issue of digital violence against women. This in turn contributes to the bigger struggle of mainstreaming the conversation into broader societal processes.”

As Sandra Aceng, the executive director of Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET), points out:

“By acknowledging tech-related violence against women and girls as a human rights issue, it shifts digital violence from being seen as a mere ‘online issue’ to a serious human rights concern requiring legal and institutional responses.”

Despite the disparities that women face around online access, Resolution 522 recognises that they are disproportionately affected by online harms, and, as Dube points out, “it goes further by acknowledging the risks/challenges women face in the digital realm, which include: cyberbullying, online harassment, and the non-consensual sharing of intimate images.”

Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) project officer Patricia Ainembabazi views the resolution as an important advocacy tool – “a flag that can be raised in holding states accountable for women’s digital rights.”

Delivering on the recommendations

With cyberspace identified as the new frontline for attacks – particularly on women journalists, human rights defenders, electoral candidates and LGBTQI+ communities – gathering empirical evidence is imperative.

For a long time, a significant deficit in the fight against digital violence, particularly in the Global South, was the lack of comprehensive research. The first major report, UNESCO’s Online Violence Against Women Journalists: A Global Snapshot of Incidence and Impacts, published in 2020, included 900 participants and highlighted the global nature of the issue. However, it also underscored the paucity of research that was specific and contextually related to the Global South.

Resolution 522 has spurred numerous organisations across the continent to conduct research into the frequency and nature of digital attacks, as well as the forms and manners these attacks take. As Dr. Moyo confirms, “MISA has used the resolution as a stepping stone to research online violence against female journalists as it provides a strategic baseline critical in pushing the needle in this crucial conversation.”

“The CHR will be undertaking a continental study on technology-perpetrated violence against women, which was conceptualised in partnership with the ACHPR following the adoption of the resolution,” advises Dube.

Titus describes how the NMT Media Foundation’s groundbreaking research into online hate speech against the LGBTQI+ community in Namibia is “viewed through an intersectional lens that powerfully reveals that discrimination extends far beyond sexual orientation or gender identity. This study illuminates how intersecting identity markers – including race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and professional standing – compound the challenges faced by LGBT+ individuals, amplifying their vulnerability in both digital and physical spaces.”

Understanding the profile of attackers and their targets is crucial, as this data-driven recommendation will facilitate safer, suitable and beneficial advocacy efforts that in turn enhance the effectiveness of interventions aimed at curbing digital violence by member states, civil society organizations (CSOs), advocates and the media.

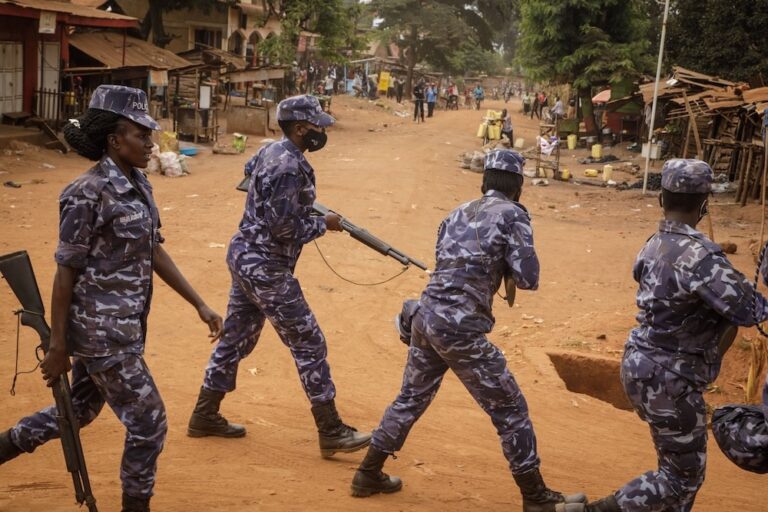

Amnesty International’s most recent report illustrates how the enactment of Uganda’s Anti Homosexuality Act has led to a sharp increase in online harassment against the LGBTQI+ community in the country. It “has forced LGBTQ individuals and organizations to alter their digital presence and behaviour. Many have been forced to deactivate their accounts, delete and/or censor posts, unfollow accounts that post LGBTQ content for fear of being outed, and also had to limit the content shared on organizational websites, which has impacted the reach of LGBTQ rights messaging and advocacy,” reveals the report.

Merits and shortcomings

Dube of CHR, Aceng of Wougnet, CIPESA legal officer Edrine Wanyamba, and Ainembabazi are united in the belief that the resolution provides a strong basis for African states to adopt or strengthen legislation to protect women from digital violence.

Wanyamba and Ainembabazi pointed out that Kenya and Nigeria are currently having discussions that centre around strengthening online safety policies, while South Africa’s Cybercrimes Act 19 of 2020 includes provisions to address online harassment and image-based abuse that are in line with recommendations made in Resolution 522.

Dube admits that “while much work remains in terms of policy formulation and enforcement and in ensuring that women are protected online, Resolution 522 has provided a clearer basis for advocates and activists to advocate for stronger protections against digital violence.”

“This is critical in countries where existing laws either inadequately address digital violence or fail to consider its gendered impact,” observes Aceng. She also pointed out the need for African countries to put resources into implementation of these laws to effectively mitigate against digital violence.

Ainembabazi suggested that the resolution provides for digital platform accountability measures, as it prompts intermediaries like Facebook (Meta), X, and TikTok to adopt provisions that define and restrict offensive content, thereby helping to address and mitigate abuse against women in online spaces.

There was consensus on the importance of engaging with tech companies, with Titus highlighting that platforms often fail to adequately protect users, allowing hate speech to spread:

“This neglect by digital giants creates environments that undermine democratic participation and jeopardise users’ mental and emotional health.”

Aceng emphasised the importance of collaborating with tech companies to design safer online platforms, and Ainembabazi suggested that the resolution provides for digital platform accountability measures, as it prompts intermediaries like Facebook (Meta), X, and TikTok to adopt provisions that define and restrict offensive content, thereby helping to address and mitigate abuse against women in online spaces.

Through my conversations with Sandra Aceng, Patricia Ainembabazi, Hlengiwe Dube, Dr Tabani Moyo, Zoe Titus, and Edrine Wanyama, I’ve come to a stronger understanding of how a resolution – essentialy ideals on paper – adopted by a continental member state body, can be purposefully used to drive advocacy around a critical issue.

The biggest drawback mentioned by all the people I spoke with is a lack of awareness of Resolution 522 by the advocates and civil society organisations working on digital inclusion and digital rights. This needs to be corrected immediately. Below, I share all of the recommendations that came out of these conversations – actions which should be taken if we are to fully realise the potential of Resolution 522:

Governments

- The alignment of legislation to underpin the rights recommended in Resolution 522.

- The facilitation of engagements with law enforcement agencies – the judiciary and the police – to ensure comprehensive understanding and enforcement of the resolution.

- Development of effective monitoring mechanisms of technology facilitated gender-based violence.

- Utilising simple and effective communication tools to spread awareness about Resolution 522.

Civil Society Organizations (CSOs)

- Active participation in dialogues with national and regional authorities to ensure the adoption and implementation of effective measures aligned with Resolution 522.

- Continuous engagement with relevant stakeholders to push for necessary legal changes that address digital violence.

- Provision of support to women in reporting incidents of digital violence.

- Empowering women on digital resilience through education and resources.

- Launch campaigns to educate the public about the harmful impacts of online abuse, using accessible formats like podcasts and videos.