The 9th annual Internet Governance Forum will be held in Istanbul from 2 to 5 September. Reporters Without Borders will be there to denounce the increasing violations of freedom of information in Turkey and to argue that respect for this freedom should be at the heart of any Internet governance model.

Read in Turkish/ Türkçe

The 9th annual Internet Governance Forum will be held in Istanbul from 2 to 5 September. Reporters Without Borders will be there to denounce the increasing violations of freedom of information in Turkey and to argue that respect for this freedom should be at the heart of any Internet governance model.

After the 2012 Internet Governance Forum in Azerbaijan, ranked 160th out of 180 countries in the latest Reporters Without Borders world press freedom index, and the 2013 IGF in Indonesia, ranked 132nd, it has fallen to Turkey (154th) to host this year’s IGF.

Launched in 2005 under UN auspices, the annual IGF is supposed to provide a neutral arena where governments, private sector and civil society discuss Internet governance mechanisms. According to paragraph 72 of the “Tunis Agenda,” the IGF’s mission is to “identify emerging issues, bring them to the attention of the relevant bodies and the general public, and, where appropriate, make recommendations.”

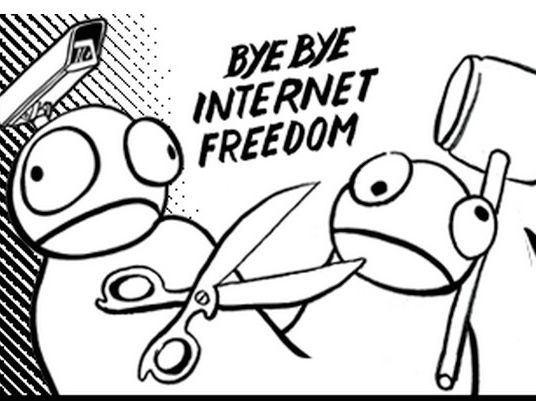

In line with this mandate, Reporters Without Borders wants the Turkish government’s assaults on Internet freedom to be raised at the Istanbul IGF.

Together with Amnesty İnternational, Human Rights Watch, the Turkish Association of Journalists (TGC) and Turkey’s Alternative Informatics Association (Alternatif Bilisim Dernegi), RWB will hold a news conference in Istanbul on 4 September in order to put the alarming decline in freedom of information in Turkey on the IGF agenda.

The Alternative Informatics Association is also holding a parallel forum, called the Internet Ungovernance Forum, in which RWB will take part.

Turkish society is becoming more and more critical of the authoritarianism of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has been prime minister for the past 11 years and who was elected president on 10 August. The scale of the “Occupy Gezi” protest movement has been eloquently indicative of civil society discontent with the government’s increasingly repressive tendencies.

Submitted in December 2013 and adopted in February 2014, amendments to Law 5651 on the Internet strengthened the powers of the High Council for Telecommunications (TIB), allowing it to “preventively” block websites on such vague grounds as the presence of content that is “discriminatory or insulting towards certain members of society.”

The Turkish intelligence agency MIT has also had its powers enhanced by a law forcing any individual or entity to surrender data on request, a provision that tramples on the right of journalists to protect the confidentiality of their sources.

The Turkish government’s ongoing talks with the US company Procera Networks and the Swedish company Netclean Technologies about the acquisition of network surveillance software are an additional source of concern.

In March 2014, on the eve of municipal elections, Turkey joined the small group of countries that have blocked Twitter and YouTube on a lasting basis. They include such repressive states as China, Iran, Vietnam, Pakistan, North Korea and Eritrea.

Reporters Without Borders points out that Internet access is recognized as a fundamental right in a 2011 report by the UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression, Frank La Rue.