On 9 December 2016, Zehra Doğan was freed from Mardin Women’s Prison where she had been held since July, charged with membership and propaganda for a terrorist organisation. But there is little to celebrate. Her trial opens in February 2017, and, if convicted she could spend years more in prison.

On 21 July 2016, a week after a coup attempt had been quashed in Turkey and stringent state of emergency regulations had been imposed, Zehra Doğan, a 27-year-old artist and journalist with JİNHA, an all-female news agency, was arrested. She was taken to a local detention centre, then on to Nusaybin, a city around 60km away. On 29 July, she was charged with being a member of and making propaganda for an ‘illegal organisation’, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

According to JINHA, Doğan heard that she had been identified as a suspect by anonymous witnesses. None were able to name her, and one witness could identify her only as “a short lady with a nose ring”.

Prosecutors added that social media posts and Doğan’s paintings were among the evidence against her. The fact that she had access to areas said to be under PKK control was another accusation, the suggestion being that she would have needed links to the organisation to be able to do so. Doğan retorted that any allegations related entirely to her legitimate to her legitimate work as a journalist.

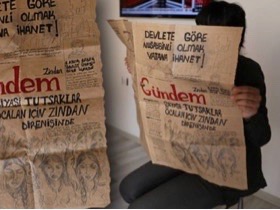

As a painter Doğan’s subjects are often Kurdish women depicted in bright, exuberant poses and colours, but she also paints darker images of war and conflict. Her creative spirit and her commitment to journalism followed her into prison, where she was among a group of women who created a hand written and illustrated edition of the Özgür Gündem (Free Agenda) newspaper that they renamed Özgür Gündem Zindan (Free Agenda Dungeon).

The original Özgür Gündem is a newspaper produced in Istanbul but aimed largely at Kurdish speaking readers. It has faced persistent harassment and closures. In May 2016 a solidarity campaign with the newspaper was launched where journalists, academics, writers, artists and others acted as one-day ‘guest editors’. As a result, 37 guest editors were arrested, and several remain in prison as of December 2016. In August 2016 the newspaper was ‘temporarily closed’ on grounds of ‘terror propaganda’. The women prisoners’ edition found its way out of the prison when visitors took photos that they then posted on social media.

JİNHA was forcibly closed on 29 October 2016, one of over 100 media outlets shut down since the failed coup, but it continues to report through Facebook and Twitter. Around the same time, Turkey’s fragile peace process that had more or less held since 2009, collapsed, and hostilities resumed.

Zehra Doğan was imprisoned in the early days of the emergency rule. During her months in prison, the situation has worsened. By December 2016, according to the International Crisis Group 2,393 people have been killed in clashes in the south east since July 2015, among them almost 400 civilians. All over Turkey more than 30,000 people have been arrested, and around 100,000 suspended from their jobs, among them academics and teachers. 1,500 NGOS have been closed, and over 80 journalists are in prison with many more on trial. On her release, Doğan observed: “I am very surprised. This world is worse now than the last one I saw.”

I want to repeat Picasso’s teaching: Do you really think that a painter is just someone who uses her brush to paint bugs and flowers? No artist turns her back on society; a painter needs to use her paintbrush as a weapon against oppressors.Zehra Doğan in a statement made from prison