When the municipalities of Diyarbakır, Batman and Hakkari, all run by the Kurdish opposition party, were seized by the Turkish government under state of emergency rule, one thing the appointed trustees all made sure of was to take municipal theatres out of operation.

The oppressors attack art first, because art is freedom.

Actress Rugeş Kırıcı

Mehmet Emin Yalçınkaya, an actor, director, playwright and translator who has been involved with the Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre (DBŞT) since its founding in 1990, was on tour with the theatre in Iran when various municipalities were placed under state of emergency decrees.

Süleyman Soylu, the interior minister, announced on 9 September 2016 that the administrations of 28 municipalities would “no longer be in the hands of terrorists.” Most of these municipalities were run by DBP, the sister party of HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party), Turkey’s main Kurdish opposition.

The municipality of Diyarbakır’s Sur district, where Yalçınkaya worked, was also on the list.

As of 5 January 2017, 51 municipalities run by the DBP (out of 106) have been taken over with state of emergency decrees due to alleged ties to the PKK, deemed a terrorist organization by Turkey. 72 mayors from the DBP are under arrest.

Actors reassigned as municipal police

Upon their return to Diyarbakır – the de facto capital of Turkey’s Kurdish southeast – Yalçınkaya and two other actors from the city theatre, Vural Tantekin and Şahabettin Dağ, were told they were assigned by the trustee to work in the municipal police department. The set carpenter Recep Ertli and prompter Hasan Bükey were moved to the public works department and assigned to various labour intensive tasks such as carrying sand for a playground. They were in fact already formally listed as staff of these departments, but this had previously been an arrangement on paper only – until the trustee took control of the municipality.

Yalçınkaya said that he had to go to the police station for a couple of days, but didn’t wear the uniform. He points out that this would have felt quite awkward. Having acted in the city theatre for more than 25 years (as King Claudius in “Hamlet”, Creon in “Antigone”, and Mem’s uncle in “Mem û Zîn”, among other roles) as well as on national television series, his face is well known in the city. “I told them I was there for acting and didn’t want to take on the role they found appropriate for me,” he said, in an interview conducted over the phone.

It was such a source of prestige for Turkey that a municipality theatre in this country staged ‘Hamlet’ in Kurdish for five years. Despite all the hardship, we will somehow continue to serve this city’s need for Kurdish theatre.

Actor Mehmet Emin Yalçınkaya

None of this is actually new to Yalçınkaya. In 1994, when the Islamist Welfare Party (RP) won Diyarbakır’s municipal elections, the theatre was shut down and Yalçınkaya was “exiled to the sanitation department,” as he puts it. He worked as a cleaner in the municipality during the day and as an actor at night. After a while, he left to work for private theatres, coming back in 1999 when Kurdish HADEP won the Diyarbakır municipal elections. “There was and is no tolerance for Kurdish theatre,” Yalçınkaya said.

Despite the theatre workers’ attempts, the trustee refused to meet with them, and they all submitted requests to leave their positions without losing the benefits they had earned over the years. Yalçınkaya was fired the next day, on 25 October 2016, with a note stating that he would not be given any benefits. He said the municipality owes him more than 150 thousand Turkish Liras (about 42 thousand USD) and that he has filed a lawsuit against these sanctions.

On 4 January 2017, all the remaining 31 actors and actresses were fired. All they received was a note citing new regulations passed by the trustee in December and announcing that their contracts would not be renewed this year.

For the past five years, DBŞT has focused on world theatre classics, and since the 2006/2007 season, all of their plays have been in Kurdish. Aside from its performances, Yalçınkaya said the theatre brought a vibrancy to social life in the city, with the annual high school theatre festival, Kurdish scriptwriting contest, international theatre festival and many workshops. The municipality was also about to open a new cultural centre that he excitedly describes as “the sixth biggest” in Turkey.

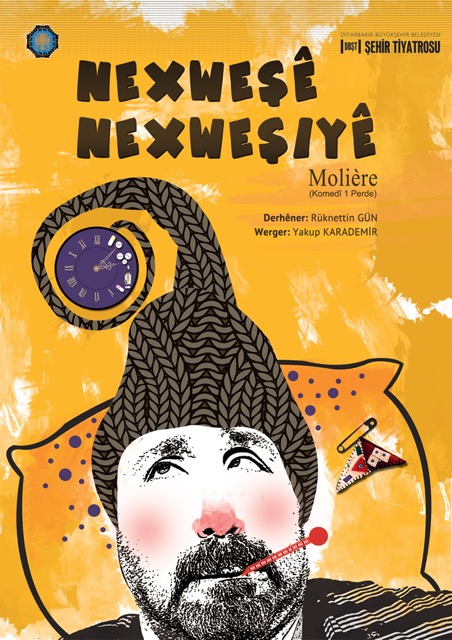

Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre (DBŞT) poster

“This theatre was Turkey’s face in Europe,” Yalçınkaya said, pointing out that they have partnered with theatres all over the world, including Theater an der Ruhr in Germany and Theatre Rast in Holland. “It was such a source of prestige for Turkey that a municipality theatre in this country staged ‘Hamlet’ in Kurdish for five years. Despite all the hardship, we will somehow continue to serve this city’s need for Kurdish theatre.”

Crackdown on the arts

The crackdown in Turkey following the state of emergency has taken a hard toll on the arts and culture scene in many Kurdish cities. Along with Diyarbakır, Batman and Hakkari’s municipal theatres were put out of operation by government-appointed trustees. Some of their workers were assigned to jobs in other departments and some were fired.

Though no municipalities in Istanbul were seized, 21 performers from the Istanbul Municipal Theatre – employed by the municipality’s subcontractor company – were dismissed on August 1 with state of emergency measures. After social media campaigns, 13 of them were reinstated.

The state of emergency has shed light on the situation of artists’ rights prior to the coup attempt – many theatre workers from different cities seem to have been contracted under different employment titles.

Over 1,400 associations and foundations have been shut down with state of emergency decrees as well. Kurdish arts and culture associations with prominent theatre companies, such as Seyr–î Mesel in Istanbul and various branches of the Mesopotamia Cultural Centre (MKM), are among those permanently shut.

Mardin Children and Youth Theatre Festival had to be cancelled because the organizing association was shut down right before the festival’s opening, due to state of emergency decrees. After much struggle, they were allowed to reopen with another emergency decree, and announced their plans to hold the festival in 2017.

Amed (Diyarbakır) Theatre Festival, which was going to be organized in the city for the fourth year, had to be held in other cities because the municipality was seized.

No staff left at Batman Municipality Theatre

The media learned that Batman Municipality’s theatre and opera had been shut through a tweet posted by the director, Ahmet Bülent Tekik, on 30 September. He wasn’t told why the theatre and opera were being locked up. “I just received a note, stating that it was found necessary,” he said, in an interview conducted over the phone.

Tekik was reappointed to work as a mechanical engineer in the municipality’s Parks and Gardens Department, where he’s still employed. He explains that his university degree is in mechanical engineering, and on paper, he had been previously staffed in the Parks and Gardens Department.

Aside from him, Tekik said all eight theatre staff – employed by the municipality’s subcontractor – were fired, and prevented from getting severance pay and other benefits with an emergency decree.

Batman Municipality Theatre staging an adaptation of Yaşar Kemal’s novel ‘Sultan of Elephants’ in April. Tekik is in the top right, with the sunglasses. Photo: Jinha

Tekik believes the theatre, founded in 2011, made a big difference in the city’s cultural scene. They staged about a dozen plays; he has acted in some, mostly in Kurdish. The municipality’s opera was also very active last year, taking part in “Hasankeyf Orchestra” (Orkestraya Netewîya Heskîfê) with Kurdish musicians from Iraq, Iran and Syria. The municipality was about to open a new theatre hall designed to seat 400 people.

Last year, when they brought children from schools to the theatre for a children’s play in Kurdish, Tekik noticed that in the beginning of the play, children answered in Turkish even when they were asked questions in Kurdish. However, they started speaking in Kurdish as the play progressed. “It meant a lot to us, scientifically and emotionally” he said.

“We used to practice in soccer fields”

Feqiyê Teyran Arts and Culture Centre (Navenda Çand û Hûnera Feqiyê Teyran), named after a famous 17th century poet from Hakkari, was founded in 2010 as part of Hakkari Municipality.

Actor Adem Bozkurt has been involved with the theatre for more than five years. In an interview conducted over the phone, Bozkurt explained that he worked for four years as a volunteer, and joined the staff as an acting teacher less than a year ago. Though he was finally getting paid, he said the staff spent almost half of their salaries on things needed for the theatre since the municipality’s budget was very limited. “We had a tiny stage, and the decor was always the same, but we wrote our plays accordingly. Even kids brought some props from their homes,” he said.

Despite these difficulties, Feqiyê Teyran was a haven for the artists. Bozkurt said that before the centre was opened, there was no venue in the city where they could stage plays. There was only one public venue, the Atatürk Cultural Centre, and they were never permitted to use this space since all their plays were in Kurdish. “We used to practice outdoors, sometimes on football fields,” he said.

Adem Bozkurt (first on left) in ‘Wedding’, a play he also directed in August 2016

In August 2016, Bozkurt directed ‘Wedding’, a play that criticized some of the wedding traditions in the city. It was staged three times, once for the launch, once for children, and a third time due to public demand. The play was widely covered by the media, including Milliyet, a mainstream daily owned by a family with close ties to President Tayyip Erdoğan and the ruling AK Party.

Shortly after, at the end of the month, the theatre was raided. The police, who apparently had “intelligence on militants about to attend a meeting,” broke various doors to enter the theatre in the municipality building, closed due to a national holiday. Their small stage was also broken by the police. Bozkurt said that families stopped sending their children to the theatre after the police raid.

When the municipality was seized by the government in September, Bozkurt was fired. He saw that he was no longer employed there when he checked his government records online. “Nobody even told me I was fired, let alone why,” he said.

The stage in the municipality building was broken by the police during a raid in August. Photo: hakkarihabertv.com

“Banned theatre groups of the banned language”

Many prominent Kurdish arts and culture associations were also closed under state of emergency decrees.

Founded in 1991, Mesopotamia Cultural Centre (Navenda Çanda Mezopotamya) is the oldest and most established Kurdish arts organization, with branches all over Turkey. On 22 November, Mesopotamia Cultural Centre’s branches in cities such as Diyarbakır (Dicle Fırat Cultural Centre), İstanbul (Med Kültür Art Association), İzmir, Mersin, Adana and Adıyaman (Pale Cultural Centre) were permanently closed down by an emergency decree.

Published in the government’s official gazette, the decree claims that all 375 foundations to be shut are “related, belonging to or in contact with terror organizations and structures acting against national security.”

For 13 years, Rugeş Kırıcı has been working as an actress at Teatra Jiyana Nû (New Life Theatre), a theatre founded in 1992 within Mesopotamia Cultural Centre İstanbul. (Teatra Jiyana Nû was not closed because the Istanbul branch is registered as a company and not as an association.) In an interview over the phone, Kırıcı said that many branches of MKM had active theatre groups, such as “Yekta Hevi” in Diyarbakır’s Dicle Fırat Cultural Centre, “Arzeba” in Mersin and “Teatra Med” in Adana. “The banned theatre groups of the banned language,” she called them.

In November and December, in solidarity with Amed (Diyarbakır) Theatre Festival which couldn’t be held in its hometown, the company staged Brecht’s ‘The Exception and the Rule’ (‘Qayde û Îstîsna’) in Cologne, Mülheim and Paris. “The festivals held in Kurdistan, including the Amed Theatre Festival, are rights we have earned with huge struggles,” Kırıcı said. “The oppressors attack art first, because art is freedom.”

Rugeş Kırıcı is on left, staging ‘The Exception and the Rule’ with Teatra Jiyana Nû in Kurdish. Photo: Bawar Mohammad

“We were shut because we act in Kurdish”

Seyr-î Mesel Theatre was founded in 2002 by a young group of Kurdish performance artists, in a top-floor flat previously occupied by a shoe manufacturer, right by İstiklal Street in Beyoğlu, Istanbul. In a phone interview, actress Yüksel İnce, a member of Seyr-î Mesel Theatre, said they were Turkey’s first independent and private Kurdish theatre company.

The theatre’s name, Seyr-î Mesel, roughly translates to “story watching”. Often inspired by Kurdish tales, myths and historic events, they have staged 15 plays, mostly in the Kurdish dialects Kurmanji and Zazaki. İnce said that their plays in Turkish have been staged in public schools as well. Aside from theatre workshops offered every season, they have had classes in cinema, music, writing and Kurdish language, as well as movie screenings, music sessions and panels.

Actress Yüksel İnce as Carmela in ‘Ay Carmela’. Photo: Sedat Sun

On 22 November, under the same emergency decree that shut down Mesopotamia Cultural Centre’s branches, the association that runs Seyr-î Mesel was also banned. After the decree, the police came to the theatre, made a list of everything to be seized – including their entire archive, computers, sound and light systems, decor, costumes – and left with a seal on the door.

“We were banned because we act in Kurdish,” İnce said. They are starting legal action and plan to follow through until their case reaches the European Court of Human Rights.

“We know the outdoors quite well from experience,” the theatre company wrote in a declaration against the shutdown. They have performed in cities without stages, in candle light when there was no electricity, on mountain tops and by rivers. But for now, they will keep rehearsing at a friend’s cafe, “when it’s empty in the mornings,” İnce said.