Along with ramping up the volume on violence and repression in recent weeks, President Museveni has, over the years, relied heavily on putting restrictive laws and policies in place.

In 2018, President Museveni signed a bill to remove the 75-year age limit to allow him to contest the 2021 elections. The bill had first been debated a year earlier amidst a brawl in Parliament.

His anticipated win at the 2021 polls should come as no surprise. It was never going to be a level playing field. Long before, Museveni’s regime had:

- Attacked, arrested, detained and tortured political opponents;

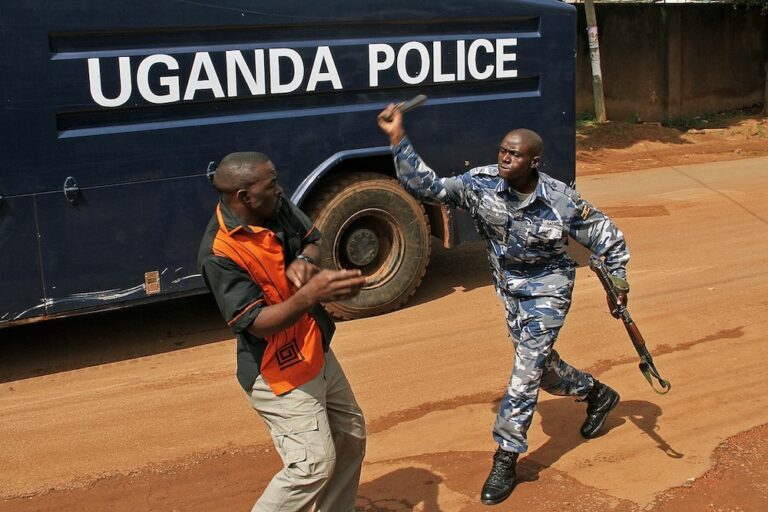

- Brutally clamped down on protests:

- Reinforced his anti-gay rhetoric by blaming the LGBTQI+ community for protests;

- Assaulted, arrested and detained media practitioners;

- Obstructed media from reporting on enforcement of COVID-19 regulations, opposition members campaigns/rallies and numerous protests over the years:

- Shut down the internet prior to the day of polling;

- Obstructed social media platforms ahead of the scheduled election;

- Denied accreditation to observer missions;

- Deported foreign journalists; and

- Introduced a new and restrictive accreditation process for journalists,

he had already tilted the electoral playing field in his favour.

Over the years, Museveni has relied heavily on putting laws and policies in place that restrict, hinder or burden citizens, while reinforcing his power. He also has a knack for presenting them as favourable for the development of the country and of benefit to citizens.

As anti-corruption activist and religious leader Bishop Zac Niringiye said many years ago: “It is no longer rule of law, it is rule by law, the law of the ruler”.

Museveni’s chokehold on power has been tested over the years, but through his ruthless campaigns he has managed to keep contenders at bay.

In his 2011 study – Bills, Bribery and Brutality: How Rampant Corruption in the Electoral System Has Helped Prevent Democracy in Uganda, Sam Tabachnik details how “running as an opposition is exasperating, infuriating and even dangerous at times.”

“As a candidate you not only have to worry about getting the support of your people but also defending your agents from abuse, defending the ballot boxes from illegal stuffing and defending yourself and your rights in court. It is taxing, financially, emotionally and physically. You have to fight all institutions for equality and fairness: the judiciary, the police, the Electoral Commission all are swayed towards the ruling party. Often times, it is a losing battle.”

The Contender

Legislator Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, aka musician Bobi Wine, has proven to be Museveni’s most formidable challenger to date. But this has come at enormous cost. Wine, who has borne the brunt of the offensive against the opposition, has been subjected to the strain of constant surveillance, unrelenting attacks, arrests, detention, and torture.

Nor have those around him been spared. On 27 December, his bodyguard Francis Senteza was killed and two journalists were injured during violent clashes between security forces and Wine’s supporters.

Often referred to as the “Ghetto President”, Wine’s music, charismatic personality, commitment, passion and – strangely enough – his “ordinariness”, are what make huge numbers of the country’s youth and members of his increasingly popular People Power Movement so devoted to him.

Although Wine has not proposed substantive remedies for Uganda’s ills, and there are concerns about his political inexperience and his ability to take up the mantle of leadership and sustain his personality-based social movement, his courage in the face of an extremely ferocious campaign gave Wine a heroic David versus Goliath persona and made him the focus of the media both regionally and internationally.

Those Ugandans who went to the polls had faced numerous obstacles intended to disenfranchise voters and campaigners alike.

Uganda had suspended all campaigning for January’s presidential polls in the capital and 10 highly-populated districts, citing coronavirus risks, but critics believe the real reason was the opposition’s popularity in these areas.

COVID-19 regulations were applied selectively to prevent meetings, rallies and gatherings of any kind by the opposition and their supporters, while the ruling party National Resistance Movement rallies were allowed to go ahead without restrictions, especially when popular Uganda rapper Bebe Cool was part of it.

Excessive force was used to quell dissent. Tragically, 54 protestors were killed and scores were injured in the two-day November protests triggered by the arrest of Wine on 18 November as he entered Luuka district to campaign. In a compelling daily series for Uganda’s Daily Monitor, journalist Gillian Nantume helped give the grim statistics a human face.

Concern and condemnation of the violence expressed by both the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner have been being disregarded.

Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) presidential candidate Patrick Amuriat, was arrested on 10 January, just four days ahead of the election, for a traffic violation. The Daily Monitor reports that, since his nomination, Mr Amuriat has been arrested nine times and charged twice with offences related to road safety and traffic.

Media threatened, attacked and suppressed

It has been a particularly tumultuous two months for the media. Journalists have been purposely targeted, tear gassed, pepper-sprayed, arrested, and detained, their mobile phones and equipment destroyed, more so when they are covering opposition news. Uganda’s police inspector general Martin Okoth Ochola brazenly told journalists:

“When we tell a journalist, don’t go there, and you insist on going where there is danger, we shall beat you for your own safety. I have no apology.”

Journalists walked out on a military press briefing in protest against the escalating violence against the media. In a tweet on 28 December Ugandan Minister of Information and Communications Technology Judith Nabakooba pledged to meet with journalists and listen to them.

The expulsion of a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation news crew, despite their compliance with the accreditation protocols, was followed by an announcement that new regulations for accreditation had been put in place.

Organisations have mounted two separate legal cases contesting the new requirements for journalists to register with the Ugandan Media Council before elections.

The first case in the High Court was brought by the Editors Guild in conjunction with the Centre of Public Interest Litigation, and sought an interim injunction to block police from executing Media Council directives before elections. Announcement of its dismissal by Judge Esta Nambayo was only declared on voting day.

The second case was a revived Constitutional challenge submitted on 5 January by IFEX member Human Rights Network for Journalists (HRNJ)-Uganda, East African Media Institute, and the Centre for Public Interest Law. The three organisations were pushing for the sections requiring registration of journalists to be set aside because it is already being contested. “Only a few media houses are registered with the council, forcing remaining media houses to deploy journalists without accreditation to cover elections,” explained Robert Ssempala of HRNJ-Uganda.

On 18 January it was reported that the High Court agreed that the directive to accredit journalists ahead of the elections was indeed “illegal and irregular”.

Digital rights under attack

Digital rights have also been undermined.

Through the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), the government requested Google close at least 14 YouTube accounts linked to Wine and his supporters, on the basis that these accounts were linked to the November riots. Head of Communication and Public Affairs for Africa at Google Dorothy Ooko said that this request would have to be in the form of court orders for Google to even consider complying.

Instead, Facebook took down a number of accounts that formed a network in Uganda linked to the country’s ministry of information. According to a VOA report: “Facebook accused the account holders of using fake and duplicate accounts to manage pages, comment on other people’s content, impersonate users and re-share posts in groups to make them appear more popular than they were.”

Just a few days before elections, Uganda blocked access to social media and messaging apps.

A plea by the #KeepItOn coalition, (made up of 65 organisations) to the government not to shut down the internet ahead of the election and instead ensure a high quality connection, fell on deaf ears. Just days before voting day, numerous organisations confirmed internet restrictions and the eventual complete blackout.

At the time of writing this piece, the internet had been partially restored. Social media apps remain blocked.

You can stay informed by following some of these organisations and journalists – @africafoicentre @cipesaug @HRNJUganda @chapterfourug @ug_lawsociety @DGFUganda17 @unwantedwitness @ACME_Uganda @rosebellk @pmwesige @solomonserwanj @natabaalo @Smith_JeffreyT @eyderp