Seven years after Philippines massacre shocked the world, CMFR asks: What can the future hold if officials only serve the rich and powerful?

This statement was originally published on cmfr-phil.org on 23 November 2016.

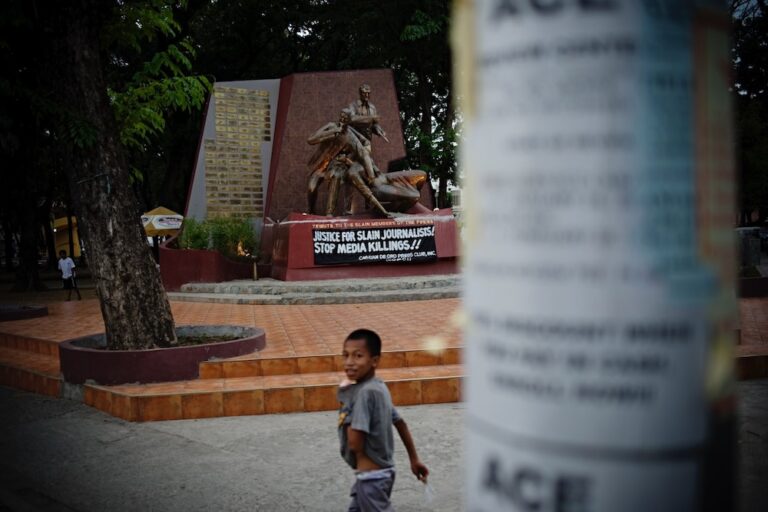

The seventh anniversary of the massacre of 58 civilians, including 32 journalists, in Ampatuan town, Maguindanao, draws our community once again to gather together, move through the motions of protest, raise voices to plea for justice for the victims and their surviving families. Some of the orphaned children are now young adults, the infants and toddlers left behind by fallen media workers are grown, with little memory of their lost parents. The widows, parents, brothers, and sisters have ceased their deep mourning perhaps because life must go on.

This year we are struck sharply by the impact of the impunity, the failure of the state to punish. Less than a week ago, a dictator was laid to rest in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, to favour his family’s request for military honours and a place for his remains among heroes. Ferdinand Marcos claimed the presidency for life, manipulating the political system, controlling the economy for his personal gain and those of his cronies, his military and police dealing with every challenge to authority with warrantless arrests and detention, torture, salvaging, causing countless dissidents to disappear. Last Friday, the military did all to please his family, as a favour to the sitting president.

Meanwhile, the Ampatuan trial has taken so long, we need to rouse our memories to revive the cause. This long wait and the Marcos burial in the LNMB are different kinds of political phenomena, but these show up the state’s uneven instruments for justice and the unequal responses to the needs of the rich and the poor. Both reflect the culture of impunity that afflicts all citizens, especially those who have no means for legal representation in courts when their rights or lives are taken.

The trial of the 195 accused in Ampatuan Massacre was designed for delay, a nod to another political alliance. A lengthy trial allows more time for highly paid lawyers to manipulate the court system, argue through technical loopholes. Delays can wear down or lose witnesses and their testimonies. Sanctioned by the rules of court, the system seems designed only for lawyers and those who can afford them.

Three years ago, in December 2013, the Supreme Court passed a resolution to allow the judge to decide cases against the accused separately, but no rulings have been made as yet on any of the persons charged. Meanwhile, the bail petition of the primary accused, Datu Andal “Unsay” Ampatuan Jr. is still pending. Indeed, the prosecution lost two witnesses who were killed in separate incidents.

Under the previous administration, an official of the Department of Justice (DOJ) had assured the public and the families of the massacre victims that there will be convictions by the end of President Aquino’s term in 2016. That deadline has now passed.

The call for justice is not for victims alone but for all Filipinos. For what can the future hold for us if the state, its officials and instruments serve only the rich and powerful? The culture of impunity is selective. Conviction and punishment are decided quickly when the offenders are poor and without the means to pay for legal defence.

This call for justice points to the need of reform of the judicial system. Its weaknesses sustain the conditions of impunity which, in turn, punishes us all equally.