The AJM found that the frequency of attacks and threats against media workers increases in turbulent political situations, especially during elections. Moreover, impunity for attacks on journalists is prevalent, an issue that requires more serious commitment from law enforcement and judicial authorities:

This article by Meri Jordanovska was originally published by Truthmeter.mk. An edited version was republished on globalvoices.org on 10 June 2022 under a content-sharing agreement between Global Voices and Metamorphosis Foundation.

Judiciary fails to initiate court procedures after journalists report threats to the police

Written by Metamorphosis Foundation

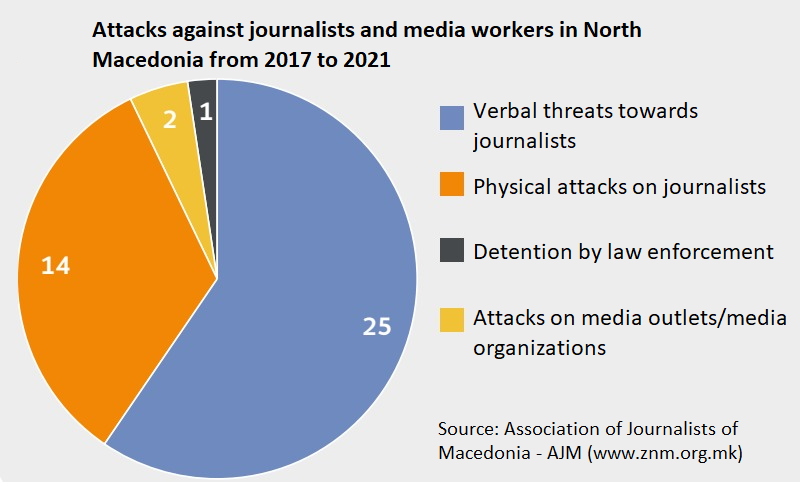

In the period from 2017 to 2021, as many as 42 attacks on journalists and media workers were registered in the Association of Journalists of Macedonia (AJM) Register. The most common form of threat to the safety of journalists is verbal threats.

Out of 42 cases of attacks on journalists, as many as 25 were verbal threats, 14 were physical attacks, two were attacks on media organizations, and one attack was in the form of imprisonment of a journalist.

This data is shown by the latest publication entitled “Attacks on Journalists and Media Workers 2017 – 2021: Tendencies and Recommendations” in which the Association of Journalists of Macedonia (AJM) covers some of the more serious violations of the rights of media workers in the country.

Types of incidents against media workers in North Macedonia (2017-2022) according to the Association of Journalists of Macedonia report. Graph by AJM, used with permission.

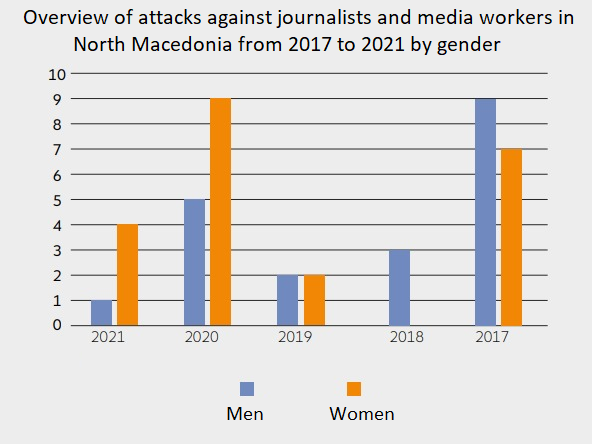

The first conclusion that can be drawn from the publication is that the number of attacks on women journalists is higher than the attacks on male journalists in the last two years.

“Sexist rhetoric is often used, giving these attacks an extra feature by the fact that they not only refer to the work of journalists, but also seem to be gender-based.”

The second conclusion in the context of the safety of journalists is that the frequency of attacks and threats against media workers increases in turbulent political situations, especially during elections. According to AJM, frequent defamatory labeling of journalists as enemies by politicians and public officials could further encourage party sympathizers to follow suit, and continue to threaten the safety of journalists and media workers in a similar manner.

The third conclusion drawn from the analysis is that physical attacks on journalists decreased during the pandemic, while online threats against journalists increased significantly.

The fourth and, according to AJM, the most important trend is the impunity for attacks on journalists, an issue that requires more serious commitment from law enforcement and judicial authorities:

What kind of attacks have media workers faced?

In 2017, 16 attacks on journalists and media workers were registered in the AJM Register. Out of these, six were verbal attacks on journalists, nine were physical assaults, and there was one case of destruction of personal property.

In 2017, the storming of the Parliament, also known as “Bloody Thursday” took place, when 20 media workers were attacked, and some of them sought justice in court. The Basic Civil Court in Skopje rejected their lawsuits. According to the AJM report:

“Meanwhile, the only ones who have received justice for the events of April 27 are politicians. Their attackers are already convicted persons. This speaks volumes about the double standards in dealing with cases of violence against journalists versus politicians, as well as the enormous degree of impunity of the attacks on journalists.”

In 2018, AJM registered three cases of attacks on journalists. Journalist Armand Braho was attacked during a conference of the Alliance for Albanians (AA) party in Struga. According to him, party members harassed him, prevented him from broadcasting the conference live, and, after the event, he was physically attacked.

The second case of an attack on journalists was registered in March 2018, when the brother of a senior official of the ruling political party Democratic Union for Integration (DUI) made a death threat to the then-president of AJM, Naser Selmani. The condemnation of the threats by the international community and a protest in front of the government led the Basic Public Prosecutor’s Office to open an investigation into the case, but it failed to press charges.

In the third case, the police detained Infomax journalist Borislav Stoilkovikj for allegedly refusing to identify himself filming and reporting a protest, although a review of the footage revealed that wore wore a journalist ID around his neck.

In 2019, four more serious cases of attacks on journalists were registered, as well as twenty other minor threats and incidents. The most serious attack was on the team of TV 21 in the Municipality of Aračinovo.

“This attack contained elements of unlawful deprivation of liberty, for which audio and video recordings were published by the media. The case was not officially reported to the Ministry of Interior, due to which the Ministry of Interior claimed that it was not able to initiate a procedure. AJM has repeatedly stated publicly that, due to the nature of the crime, it is necessary for the prosecution itself to take action ex officio. In the end, the case was not resolved, despite the fact that the mayor of Aračinovo, Milikije Halimi, publicly apologized for the incident, which confirmed that it really happened.”

AJM in 2020 recorded 12 threats against journalists, one physical attack and one attack on the media. Out of the 14 registered attacks on journalists in North Macedonia, in nine cases the victims of the attack were women journalists.

Women journalists are a more frequent target of attacks

Since the beginning of 2021, AJM has registered a total of five attacks, four verbal and one physical. What is worrying is that in 2021 most of these attacks (three) were aimed at women journalists.

Overview of attacks against journalists and media workers in North Macedonia from 2017 to 2021 by gender. Source: Association of Journalists of Macedonia – AJM, Graph used with permission.

This, according to AJM, is a continuation of the negative phenomenon observed in 2020 — the number of attacks on female journalists to be greater than the number of attacks on male journalists.

“It is interesting that in all three verbal attacks on women journalists in 2021, the threats come from political figures. It speaks a lot about the low culture of public communication in the relationship between a holder of public office and a journalist, but it also speaks about the fact that holders of public office are easily encouraged to make threats against women journalists in North Macedonia. It is important to underline that no official case has been issued by the Public Prosecutor’s Office or the Ministry of Interior, despite the fact that some of the threats were reported to the police.”

This worrying trend, according to AJM, could lead to a so-called “cooling effect” where women journalists self-censor themselves from further speaking about or researching a particular topic, or, in the most extreme cases, withdraw completely from the journalistic profession. AJM stated:

“Such inhibition is additionally driven by the inaction of the institutions or by the inefficiency in conducting investigations and gathering evidence. The Ministry of Interior as a tool in the hands of the prosecution is the only institution with access to mechanisms for gathering evidence in the online sphere where it is necessary to locate the attackers by IP addresses and the like. However, it must be noted that the final decision on whether to initiate criminal proceedings against the attackers is up to the public prosecutor’s office. The attacks on women journalists through various online platforms must raise the alarm in the institutions because living in the digital age has made the attackers braver, more confident and fiercer in their attacks.”

Very often the attacks on journalists are from anonymous profiles on social networks or so-called “bots” that use VPN (virtual private networks), so they can easily hide their tracks in the online sphere and can hardly be located even by the competent institutions. AJM noted that, in practice, the procedure for locating attackers using internet platforms is difficult and slow. In order to identify such perpetrators, better inter-institutional cooperation is required. In order to gather information across borders domestic law enforcement agencies need to use instruments of international legal assistance, which is not always effective, as will for cooperation might vary from country to country, especially when tools enabling anonymous communication had been used.

What next?

As a way out of these situations, AJM recommends several measures in order to protect journalists and media workers. Initially, the Parliament is required to pass the proposed amendments to the Criminal Code as soon as possible, where the qualified forms of the criminal acts that affect the journalists are applied. Journalists’ associations and trade unions were both consulted in the formulation of these amendments.

Furthermore, AJM demands that Ministry of Interior increase the efficiency of the work of the Department of Cybercrime and Digital Forensics in order to easily find the perpetrators of online attacks on journalists and media workers. It also calls for the establishment of special units in the Public Prosecutor’s Office and in the courts that will be trained and specialized in the safety of journalists; improving the culture of public communication between political actors in order not to encourage offline and online attacks; and monitoring and documenting hate speech and gender-based attacks on journalists in the Internet space by civil society sector, among others.

Also, in the last report on the progress of North Macedonia, the European Commission recommends that there should be zero tolerance for intimidation of and attacks on journalists.

“Attention should be paid to the labor rights of journalists. The recommendation is to impose a zero-tolerance approach to intimidation, threats and violence against journalists in the course of their profession and to ensure that perpetrators are punished.”