A roundup of key free expression news in Africa, based on IFEX member reports.

Taking on political issues through music

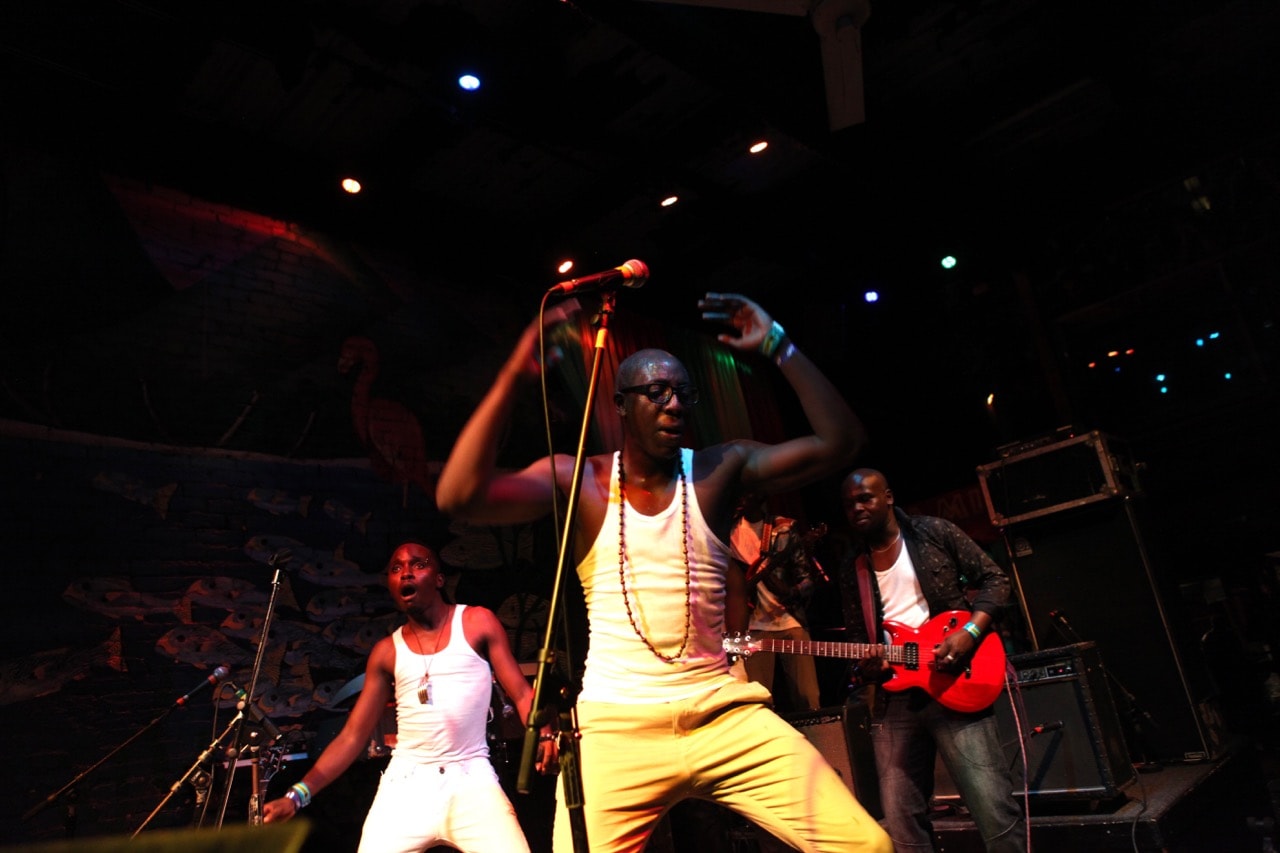

In many countries on the continent, musicians are tapping into the concerns of their audiences and fashioning their music to take up pressing socio-political and economic issues. Their popularity with younger audiences is making authorities sit up and pay attention.

Africa’s growing youth population is jobless and frustrated, and getting angrier as the chasm of disconnect between their desires and the failure of their governments to fulfil their aspirations grows wider. This feeling of being politically disenfranchised is encouraging them to tune in to musicians like Bobi Wine in Uganda, Falz in Nigeria, Sauti Sol in Kenya, and Didier Lalaye in Chad. But as these musicians grow in popularity with their youthful audiences, they are increasingly unpopular with their country’s leadership – for speaking out about critical issues – and for this, they are paying a price.

The lyrics of This is Nigeria, by rapper Falz, have been branded vulgar by the country’s censorship board, and the song has been banned. Fashioned on American artist Childish Gambino’s This is America, Falz’s version focuses on Nigeria’s drug crisis, the missing Chibok schoolgirls, and the escalating pastoral conflict in the central states of the country. Internationally it has been hailed for its searing political commentary, but the Nigerian National Broadcasting Commission disagreed. They called the song indecent and vulgar, and fined a local radio station for broadcasting it.

Kenya’s Afro pop band Sauti Sol’s new release Tujiangalie – Swahili for self-reflection – poses the question: “Is Kenya fine?” Quartz Africa describes the song, recorded in collaboration with Kenyan rapper Nyashinski, as “a poetic appraisal on the problems currently plaguing Kenya – including corruption, mounting debt, economic inequality, a crisis of leadership, and the troubling connection between the clergy and the political class. The official lyric video visually celebrates Nairobi’s dynamism, but also notes that in Kenya, democracy is just a ‘word we say for fun.'”

In Chad, slam poets are taking to the stage and prodding debate on issues such as unemployment and corruption, pollution and women’s rights, racism and inequality. A medical professional by day and slam poet at night, 34-year-old slam poet Didier Lalaye feels this his development of a mobile health service for Chadian children is not enough. He wants to bring change through his poetry.

Fallout from political turmoil felt by journalists

The attacks on journalists and activists in Uganda during August were relentless.

A politically charged municipal by-election campaign in the district of Arua in Uganda catapaulted into an explosive situation when the police and military intervened, assaulting and arresting members of parliament, journalists, and citizens. The government claimed the heavy-handed intervention was necessitated because President Yoweri Museveni’s convoy had been attacked by opposition supporters.

The shooting of his driver and subsequent arrest of musician-turned-politician Robert Kyagulanyi, aka Bobi Wine, along with other opposition party members, sparked further protests in Kampala and other parts of Uganda. The fallout from this political turmoil cascaded onto activists and the media sector.

Journalists who covered the Arua by-election – and the ensuing events surrounding the arrest, torture, rearrest, and prevention of Wine leaving the country to seek medical treatment – were beaten, or arrested on spurious charges.

This brutal treatment of Wine, affectionately known as “the Ghetto President”, is likely intended to break his spirit and intimidate the opposition. Following the usual pop culture trend, the dreadlocked Wine sang about women and drove fast cars. In the middle of this phase of flash and swagger, he shifted his approach and wrote a song calling for peaceful elections and a handover of power, which became a hit. In voicing the sentiments of a growing young and frustrated citizenry, Wine’s increasing popularity among a politically active and youthful population poses a serious threat to President Museveni’s continued leadership.

Constriction of media freedom in Nigeria

Over the last year Nigerian media advocate organisations have expressed growing concern at the frequency of attacks on the media, in addition to the already worrying slow and subtle narrowing of the space for media freedom.

After years of refuting reports they had arbitrarily detained him, the authorities finally released journalist Jones Abiri on 14 August, on bail, after two years in prison.

Abiri went missing on 21July 2016, after heavily armed Department of State Services agents arrested him outside the office of the Weekly Source newspaper. During his enforced disappearance he had no access to his family or lawyer or to medical treatment. The authorities were silent on his whereabouts, despite persistent inquiries from regional and international media lobby groups, activists and journalists. It was the amplified pressure during the annual International Press Institute (IPI) conference held in Abuja by media organisations, and the eventual fundamental human rights enforcement suit filed by human rights lawyer, Femi Falana, on behalf of Abiri, that pushed the DSS to bring him to court.

As Abiri was being released, Samuel Ogundipe, a reporter with the privately owned Premium Times online newspaper, was detained by the police and forced to reveal the source of information for an article he had written. His bank account was also frozen on the same day.

The outrage at his arrest spilled out on to the streets, as Nigerians marched to police headquarters in Abuja. The protestors fled when police fired teargas canisters at them, but then regrouped and marched back to the headquarters, demanding the journalist’s release.

Ogundipe was released two days after his arrest, only after his bail conditions, “N500,000 Naira and a surety, resident within the jurisdiction of the court”, were met.

Free expression and the law: From surveillance to cartoonists

In early August, the Right2Know Campaign and Privacy International applied to be admitted as friends of the court in an ongoing legal challenge to South Africa’s surveillance law, RICA, in the High Court in Pretoria. The intervention is based on mounting evidence that the South African state’s surveillance powers are being abused, and so-called “checks & balances” in RICA have failed to protect citizens’ constitutional right to privacy.

A constitutional challenge by Media Rights Agenda (MRA), Paradigm Initiative and Enough Is Enough Nigeria has moved to the Supreme Court. The three organisations are challenging Section 24 and 38 of the Cybercrimes Act, which refers to cyberstalking, and asking they be removed from the Act. The Nigerian authorities have been repeatedly and erroneously using this section to harass and persecute journalists and critics. “It’s arguably the most dangerous provision against freedom of speech, opinion and inquiry,” explained Tope Ogundipe, Paradigm Initiative’s director of programmes.

For just a moment, the media sector breathed a sigh of relief, when they learned that the revision of Rwanda’s penal code now allows general defamation to be reported to an independent body – the Rwanda Media Commission. However, all this was negated by an additional clause that now criminalises the drawing of cartoons that portray politicians and leaders in an unflattering manner, which will have an adverse effect on media freedom and freedom of expression.

Steep accreditation fees considered an assault on media freedom

A few months ago, the Mozambican government issued a decree requiring journalists obtain media accreditation and pay excessively high accreditation fees. Decree 40/2018, which came into effect on 22 August, requires foreign correspondents to pay US$2 500 per trip to Mozambique for media accreditation. Locally based freelance journalists will be charged US$500 per year, while foreign correspondents based in Mozambique will be required to pay an annual fee of US$8,300.

Organisations from the region – the African Southern African Editors Forum, the Foreign Correspondents Association of Southern Africa and the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) – Mozambique, along with the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and IPI, have jointly taken a stance against “the imposition of the prohibitive accreditation fees for foreign correspondents and local journalists working for foreign media organisations”. They issued a statement urging the Mozambican government to withdraw the exorbitant accreditation fees.

Deprose Muchena, Amnesty International’s regional director for southern Africa, predicts the excessive accreditation fee will inadvertently have an impact on the stories coming out of Mozambique, with media outlets opting not to pay fees for their journalists. MISA Mozambique called the government move “an attack on journalists and an attempt to suppress the small media groups.”