May 2021 in Asia-Pacific: A free expression roundup produced by IFEX's regional editor Mong Palatino, based on IFEX member reports and news from the region.

The month of May saw the further deterioration of free speech in Hong Kong, Cambodia, and Myanmar. Amid the pandemic surge, India is engaged in a legal battle with tech companies and civil society about its new IT rules. But there were also some victories to inspire us, including the landmark legislation for the protection of journalists in Pakistan’s Sindh province, and Mongolia’s new law for the protection of human rights defenders – the first of its kind in Asia.

Good news…

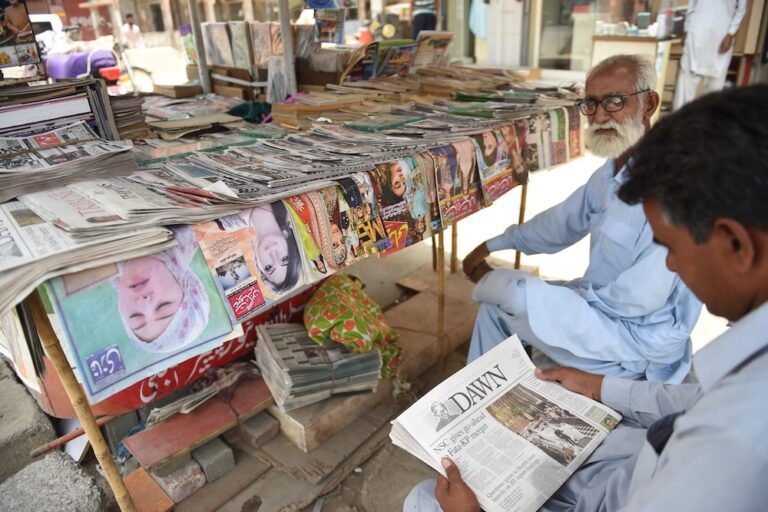

The provincial Sindh Assembly in Pakistan has unanimously passed the Sindh Protection of Journalists and Other Media Practitioners Bill, 2021. IFEX member Pakistan Press Foundation (PPF) describes it as “a milestone in efforts to provide safety for Pakistani journalists.” The new law would lead to the creation of a “robust, inclusive, and autonomous” Commission on Safety of Journalists and Other Media Practitioners composed of both government representatives and media stakeholders. A similar bill is also pending in the Pakistan’s National Assembly, where it is awaiting deliberation by the Human Rights Committee. PPF has played a leading role in the campaign after it presented the draft bill in February 2020 in the federal cabinet.

In Australia, IFEX member Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance welcomed the recommendations of a Senate inquiry into press freedom which “would help to curb the growing culture of government secrecy, stop the persecution of whistleblowers and prevent journalists being prosecuted for simply doing their jobs.” The senate conducted the inquiry after media groups including MEAA raised concerns regarding the raids conducted by the police targeting News Corp and ABC journalists in 2019.

In Mongolia, the parliament has approved the Law on the Legal Status of Human Rights Defenders. UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet noted the significance of this legislation. “As the first country in Asia to enact such important legislation, the law will resonate within and beyond Mongolia’s borders.” Civil society groups also welcomed the law but highlighted two provisions which “could be misused to delegitimise the work of human rights defenders.”

and bad laws…

After passing the Information Technology (Intermediary Guideline) Rules, 2021 in February, the Indian government has given tech companies three months to comply with the requirements. Several court petitions were filed questioning the legal bases of some provisions that could violate the privacy and access to information of internet users. WhatsApp and Facebook raised the issue of traceability related to encryption services. IFEX member SFLC.in assisted some petitioners in addition to releasing its legal analysis of the rules. It also summarized the contentious issues highlighted by the petitioners, the response of the government, and shared a timeline of legislation focusing on internet regulation.

The Vanuatu parliament amended the Bill for the Statute Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act No. of 2021 which stipulates that “threatening language, criminal Libel and criminal slander on any public platform could warrant a criminal offence and offenders could face three years imprisonment.” IFEX member the Pacific Freedom Forum has warned that this could be used to attack journalists who publish reports critical of politicians and government policies.

Dozens of media groups and journalists in the Philippines, including IFEX member the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR), have signed a statement rejecting the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 for containing provisions that “trample upon fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of the press.” The Supreme Court is currently handling an unprecedented 37 petitions challenging the constitutionality of the law.

In a letter addressed to Indonesia’s Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, IFEX member Human Rights Watch (HRW) is calling for the suspension and revision of the Ministerial Regulation 5 (MR5), which requires all private digital services and platforms to register with the government. HRW said MR5 poses risks to “privacy, freedom of speech, and access to information of Indonesian internet users.” It obliges tech companies to filter ‘prohibited content’, take down content in four hours if the government request is certified as ‘urgent’, and monitor online activities “causing public unrest or public disorder”.

Record low Hong Kong press freedom index

Rising attacks and legal harassment targeting journalists critical of the Beijing government were reflected in the annual survey of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, which showed a record low press freedom index for Hong Kong. The deterioration in media freedom is linked to the passage of the National Security Law, which practically revoked Hong Kong’s autonomy. In recent months, authorities have intensified their crackdown on pro-democracy leaders, including filing cases against reporters who were simply covering 2019’s massive protests.

Aside from being threatened with dismissal from work, some journalists have been subjected to physical attacks.

Another troubling indicator is the undermining of editorial independence in RTHK, a public broadcaster which is now being turned into a government mouthpiece.

After convicting activists who had participated in the annual 4 June Tiananmen Massacre anniversary vigil in 2020, Hong Kong authorities have once again banned any activity commemorating the event this year. It reflects the stricter controls imposed by Beijing aimed at silencing dissent in Hong Kong.

Persecution without borders… and courageous defiance

Suppression of free speech continues to worsen in Myanmar as the coup enters its fourth month this June. The numbers are staggering. As of 30 May, 840 individuals have been killed by security forces, 5,529 have been arrested, and 4,409 are currently detained. A total of 86 journalists have been arrested, 49 of whom are still behind bars.

After banning several independent media networks, Myanmar’s military regime has criminalized the use of satellite television, which will prevent residents from accessing information provided by foreign channels and alternative local broadcasters.

The situation of journalists has become more dangerous as authorities continue to be intolerant of reports exposing the atrocities committed during the coup.

Many journalists have risked their safety and well-being in order to fulfill their duty to inform. Some have been forced to flee to ethnic areas and neighbouring countries. But even those in exile continue to face threats. Three Democratic Voice of Burma reporters were arrested in Thailand on 9 May.

The video below documents the efforts of IFEX member Mizzima, forced to go into hiding after being banned by the junta, to continue broadcasting.

Four foreign journalists had been arrested since February: Poland’s Robert Bociaga, Japan’s Yuki Kitazumi, and US citizens Danny Fenster and Nathan Maung. After being deported, Kitazumi described the conditions of Myanmar’s political prisoners. Fenster, the managing editor of news magazine Frontier Myanmar, was arrested at Yangon airport while he was trying to leave the country to visit his family. Maung is the co-founder of Kamayut Media.

Artists are among those detained or killed for peacefully resisting the coup. PEN International said poet Khet Thi (real name, Zaw Tun) was arrested on 8 May and died during interrogation. The poet’s wife, Chaw Su, reported that her husband’s internal organs were taken out. Khet Thi’s writings during the coup have inspired fellow artists and activists:

“They shoot in the head,” he wrote, “but they don’t know the revolution is in the heart.”

Soon after the coup, Khet Thi had written, “If I have only a minute to live, I want my conscience to be clean for that minute.”

Silencing critics and journalists in Cambodia

As Cambodia experienced a surge in COVID-19 cases, authorities passed new regulations that criminalized the posting of information that provokes “turmoil in society.” This became the basis for putting restrictions on media reporting and led to the arrest of several internet users who were criticizing the government’s pandemic response. Local journalists said the restrictions prevented them from reporting about the capital’s ‘red zone areas’ which “undermines the government’s commitments to protecting press freedoms and access to information.”

IFEX joined several groups in urging the government to immediately stop its assault on freedom of expression.

“The Cambodian government’s clampdown on free speech is having a chilling effect on the exercise of freedom of expression in Cambodia. The authorities’ actions are reinforcing the already widespread atmosphere of self-censorship, preventing participation in governance and public affairs, and extinguishing an important safeguard for government accountability.”

Focus on gender: Japan’s Equality Act

Various groups are urging Japanese lawmakers to pass the Equality Act, which is intended to protect the LGBTQI+ community from discrimination. An initial draft presented by the ruling party only requires the government to “promote understanding of LGBT people.” There was no explicit commitment for nondiscrimination protections. Human rights groups also reminded authorities that the immediate passage of the law is crucial since the Olympic Charter prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The Tokyo Olympics is scheduled to start in July.

In brief

In Bangladesh, investigative journalist Rozina Islam was arrested for allegedly stealing information from the Health Ministry and violating the Official Secrets Act. The senior reporter of newspaper Prothom Alo was investigating allegations of corruption and mismanagement. She was released on bail as media groups continue to call for the dropping of charges filed against her.

In Malaysia, cartoonist Zunar was summoned and interrogated by the police in connection with a cartoon he published in January lampooning a local official. Zunar’s phone was confiscated and he was not allowed to see the complaint sheet against him. ARTICLE 19 said the persecution of artists like Zunar “stifles creative expression, chills public discourse, and undermines trust in Malaysian authorities.”