December in Middle East and North Africa: A roundup of key free expression news, based on IFEX member reports.

Iraq: Masked, unidentifiable and unknown assassins

Protests in Iraq raged on last month, as demonstrators continued to call for a complete upheaval of the power-sharing political system established since the US-led invasion, which demonstrators believe is responsible for the country’s political and economic turmoil.

December saw the resignation of Prime Minister Adel Abdel Mahdi and a breakdown in efforts to find his replacement and form a new government, with President Barham Salih offering his resignation on 26 December after refusing to appoint Asaad Al Eidani, the Iran-backed governor of Basra, as the new Prime Minister.

Events in Iraq reached a fever pitch in the final week of the year as pro-Iran rioters broke into the US embassy in Baghdad in response to American airstrikes and sanctions on pro-Iranian militias, edging the country a step closer to becoming a potential battleground for a proxy war between Washington and Tehran.

Lost in the political chaos are the peaceful protesters, activists, and civilians that have been brutally targeted since protests began. Last month saw the killing of at least three journalists by militias and unidentified gunmen, while kidnappings, assassinations and torture of human rights defenders, journalists, and medical personnel, at the hands of unknown gunmen, have become a daily occurrence across the country.

According to a recent report by the UN Assistance Mission in Iraq (UNAMI), credible allegations of deliberate killings, abduction and arbitrary detention have been carried out by unknown armed men described as ‘militia’, ‘unknown third parties’, ‘armed entities,’ ‘outlaws’ and ‘spoilers’. The report also concluded that high profile activists and journalists were being targeted for arrest by both Iraqi security forces and “groups described as ‘militia.’”

Protesters in Misan province southern #Iraq light up candles for the protesters who lost their lives in yesterday’s #Baghdad attack in Sinak bridge and Khilani Square.

Photo source unknown unfortunately #IraqProtests #العراق pic.twitter.com/NwLf2Cfs1C

— Lawk Ghafuri (@LawkGhafuri) December 7, 2019

The complicity of security forces in these deaths continues to be an issue in the spotlight. According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), security forces may have coordinated with unidentifiable gunmen during an overnight 6 December attack in Baghdad’s al-Khilani Square that left dozens killed and more injured. Witnesses report Iraqi security forces abandoned the area shortly before the attack and returned minutes after it ended, cutting off electricity for at least an hour, immersing demonstrators in darkness during the onslaught.

“All we could see was light coming from the bullets,” said one protester describing the 4am attack.

Palestine: Generational repression of civil rights

A new report from HRW detailed how for more than 50 years, Israel has employed draconian military orders to suppress Palestinian nonviolent activity and decimate their basic civil rights, including freedom of expression and assembly.

For instance, the 1967 military order 101 continues to criminalize participation in a gathering of more than ten people without a permit on an issue, which the army considers to be a political gathering punishable of up to ten years. The order also prohibits the publication of political materials or the display of flags or political symbols without army approval. Meanwhile, 2010’s military order 1651 imposes a ten-year sentence on anyone who attempts to – orally or otherwise – influence public opinion in the West Bank in a manner that “may harm public peace or public order” or “publishes words of praise, sympathy or support for a hostile organization, its actions or objectives,” which the army defines as “incitement.” The vaguely worded order also states that “offenses against authorities” can carry a sentence of life imprisonment.

The real-life consequences of these orders have been disastrous for civil society and non-violent actions in the West Bank. According to the report, between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2019, a total of 4,590 Palestinians were prosecuted for entering a “closed military zone” – a designation the Israeli army imposes on protest sites in real-time – while 1,704 were prosecuted for “membership and activity in an unlawful association”, and 358 for “incitement.”

Meanwhile, in digital rights

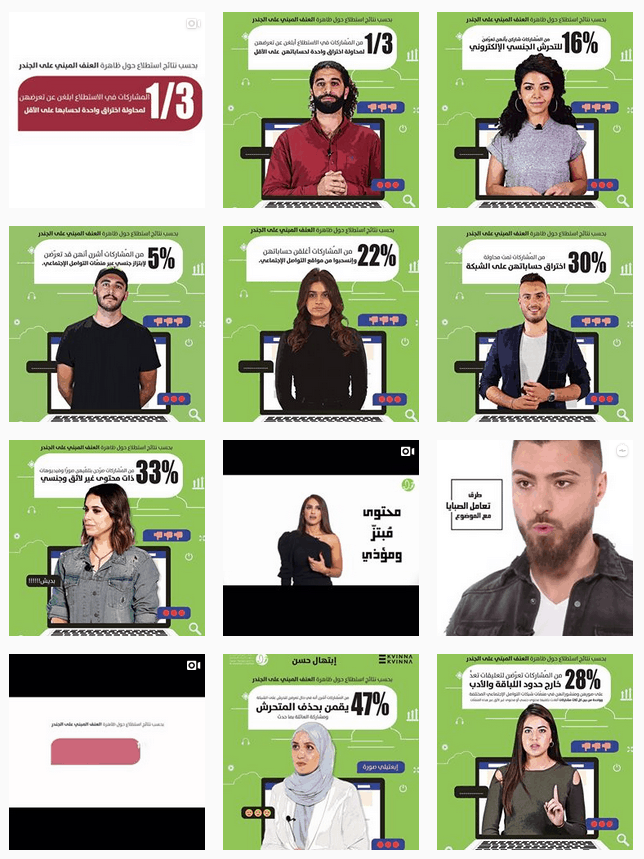

To mark last month’s 16-days of activism against gender-based violence, the Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media (7amleh) launched a campaign addressing the phenomenon of violence, harassment and extortion of Palestinian women online. The campaign saw social media influencers in the West Bank push the conversation online through infographics and multimedia, drawing on 7amleh’s research on the issue, which revealed one-third of young, Palestinian women are subjected to violence or sexual harassment online.

Saudi Arabia: a ‘mockery of justice’ for Jamal Khashoggi’s murder

It has been over a year since Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi walked into a Saudi Arabian embassy in Istanbul, never to be seen again. Late last month, the official investigation into his death came to a predictable end after the kingdom’s public prosecutor office announced it had sentenced five people to death and handed out jail terms for three others allegedly complicit in his murder, calling the crime “spontaneous” and not premeditated.

The Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR) condemned the verdicts, noting the trial lacked the minimum standards of a fair trial and due process. The rights organization also called on international bodies to ensure top Saudi officials involved in the killing do not evade justice – a call reiterated by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

“Conducting a sham trial for the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and sentencing five people to death shows that the Saudi government under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is committed to an ongoing mockery of justice,” said CPJ Middle East and North Africa Program Coordinator, Sherif Mansour. “The international community, including the U.S., must not allow Saudi Arabia to keep evading justice in the Khashoggi case.”

Dr. Agnès Callamard, the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, who investigated the killing and published her findings back in June 2019, called the verdict “the antithesis of justice”. Callamard’s UN report highlighted the extensive planning of the murder, and included audio from Turkish authorities in which a team of Saudi agents, while waiting for Khashoggi to arrive at the embassy to pick up necessary papers for his planned nuptials, can be overheard discussing how they would carry the body out of the building.

Bottom line: the hit-men are guilty, sentenced to death. The masterminds not only walk free. They have barely been touched by the investigation and the trial. That is the antithesis of Justice. It is a mockery.

— Agnes Callamard (@AgnesCallamard) December 23, 2019

While Callamard’s report concluded that the killing “was overseen, planned and endorsed by high-level officials,” the recent verdict in Saudi Arabia has provided total immunity for those very officials in the chain of command, while scapegoating those tasked with carrying out the murder.

The end-result sends a chilling message to dissidents from the region living in exile: that their safety abroad is far from secure.

“This is not just about the justice Jamal deserves, or even closure for his friends and family. This is also about deterrence; so another critic is not killed in London’s Hyde Park, abducted from a Toronto suburb or assaulted in a D.C. bar,” said Egyptian human rights advocate Mohamed Soltan in a Washington Post Op Ed. “When we seek justice and accountability, we are not seeking to avenge Jamal’s murder. We are attempting to secure an immediate future where we can live without constant fear of assassination and dismemberment.”

Egypt: “Silence and collusion are not our choices”

https://www.facebook.com/gamal.eid.90

In Egypt, IFEX member and director of the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI), Gamal Eid was attacked on a street near his Cairo home while waiting for a taxi. Eid was thrown to the ground and beaten by at least a dozen men who were waiting for him in three parked cars. With pistols drawn, the group doused Eid in red paint while warning him to “behave himself”.

This is the fourth attack on the prominent activist since October 2019, prompting a call from GCHR on international bodies like the UN to step in and protect Eid. Posting photos of the aftermath on Facebook, Eid said he believes these escalating attacks are orchestrated by security forces in such a manner as to avoid a public scandal like that of Giulio Regeni, the Italian Cambridge University graduate who was kidnapped and brutally tortured to death in Egypt in 2016.

Regeni’s death continues to receive attention, with Italian prosecutors naming five senior security officials last year as suspects in the death, and more recently, accusing Egyptian officials of fabricating contradictory stories to deliberately mislead the investigation.

“They resorted to attacking me one time after another, to punish me, silence me and stop me from doing human rights work and my frequent criticism of the gruesome human rights violations,” said Eid. “But again, silence and collusion are not our choices.”

With Egypt continuing to face an on-going violent crackdown against civil society organizations and human rights defenders, the repeated failure of Egyptian authorities to prevent these attacks and hold the perpetrators accountable is likely indicative of their complicity.

“This latest assault on Gamal Eid has the fingerprints of Egyptian security forces all over it,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at HRW. “Repeated attacks against one of Egypt’s leading rights activists raises grave concerns about the possible involvement of Egypt’s leadership.”

In Brief

Morocco

The arrest of journalist Omar Radi sparked outrage after he was summoned to a police station, detained, and put on trial on the same day over a six-month old tweet where Radi criticized a judge’s verdict of imposing sentences on 42 people for participating in the “hirak” protests in northern Morocco’s Rif region. “These shameless officials should be neither forgotten nor forgiven,” wrote Radi in the 5 April tweet, calling the judge an “executioner”.

Radi has since been released until his next trial session in March, and could face up to one year in prison under article 263 of Morocco’s criminal code, that punishes anyone “with the intention of damaging their honor, their delicacy or the respect due to their authority, shows contempt to … a magistrate.”

In recent weeks, Morocco has also sentenced prominent YouTube vloggers to four years in prison, as well as rapper Gnawi to one year in prison for supposedly criticizing the police, but more likely over his track “Long Live the People” in which he criticized the regime. A high school student subsequently received a three-year sentence for posting lyrics to Gnawi’s viral track on social media.

Moroccan rapper Gnawi has been charged with “offending” public officials in an Instagram live. His arrest comes just two days after he released a video indirectly insulting the king of Morocco pic.twitter.com/LfBbk0pa26

— Middle East Eye (@MiddleEastEye) November 15, 2019

Syria

Six years have passed since masked gunmen abducted Syrian human rights defenders, Razan Zaitouneh and her husband Wael Hamada, and their colleagues Samira Al-Khalil and Nazim Hammadi from their offices at the Violations Documentation Center (VDC) in the Damascus suburb of Douma. Last month, rights groups issued a joint statement calling on authorities to release the prominent activists, now known as the Douma Four, who were investigating war crimes committed by Syrian authorities at the time of their kidnapping. While rebel group Jaysh Al-Islam is widely believed to be behind their abduction, they remain among some 98,000 Syrians forcibly disappeared since March 2011 whose fate remains unknown.

Meanwhile, digital activists have pushed back on Twitter’s recent announcement that it would be deleting inactive accounts, which would include those of forcibly disappeared activists like Razan Zaitouneh and those killed, such as slain radio host Raed Fares. “Deleting their accounts could deal a significant blow to the Syrian memory as well as deprive us of vital evidence for use in justice and accountability processes,” said Syrian Archive’s co-founder, Hadi Al-Khatib in a recent interview.

UAE

The security apparatus has targeted dozens of relatives of Emirati dissidents who are either currently detained or living abroad. According to HRW, relatives of eight dissidents have seen their citizenships revoked, have been arbitrarily denied access to services, and have faced restrictions placed on their ability to access jobs and higher education. Relatives have also been subject to state surveillance, threats, and regular questioning by security officials who are empowered by a 2003 federal law granting the security apparatus a wide mandate to curb political activity, by force if necessary.

Documenting the region

Finally, in its annual global survey, CPJ says the number of imprisoned journalists in the region has risen, with Egypt and Saudi Arabia now ranked as the third worst jailers in the world after China. Meanwhile, although the number of journalists killed has fallen globally, Syria remains the deadliest country, with seven journalists killed in 2019.

If you enjoyed this, check out all the December regional roundups!