Over five hundred academics who signed a peace petition in 2016 asking Turkey to end violence against Kurds were banned from teaching. In response, they set up alternative venues for education and research all over the country, free and open to everyone.

The Turkish government has recently declared an end to a two-year state of emergency, in effect since a failed coup attempt in July 2016. The period had taken a heavy toll: Over 6,000 academics were banned from public duty during the emergency rule, and more than a hundred thousand people were removed from public jobs.

A new terror bill was rapidly approved by the parliament, in practice extending the emergency rule for another three years, enforcing restrictions such as a curfew on meetings and protests until dark, and giving mayors the right to ban certain areas of the city to certain people to ensure “public safety”.

It doesn’t look like the pressures on freedom of expression are ending anytime soon, including the crackdown on over 2,000 academics who signed a petition titled “We Won’t Be a Party to This Crime” in 2016 to protest military action in Kurdish majority southeastern cities, and demanding that peace talks – interrupted in July 2015 – be restarted.

The petition outraged President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who repeatedly accused the group of treason and asked “judicial authorities and university administrations as their duty to punish these acts”. Authorities complied – to date, 517 signatory academics have lost their jobs, and 405 have been banned from public duty, according to the group’s website.

The purged academics start organizing

Despite intense pressure, the expelled academics have come up with inspiring and creative ways to cope. They founded grassroots, non-institutional “solidarity academies” in ten cities in Turkey, as well as in Germany, following the exodus of academics from the country.

The first “solidarity courses” were held In Eskişehir and Istanbul, and the first Academy was created in Kocaeli, in September 2016. As of today, they are active in Ankara, Antalya, Dersim, Eskişehir (“Eskişehir School”), Istanbul (Istanbul Solidarity Academy and “The Campusless” movement), İzmir, Kocaeli, Mardin, Mersin (“Kültürhane”), and Urfa. There’s also a solidarity academy in Berlin, Germany, and an online one, “Off-University”.

All the alternative academies involve the signatory academics, and include teaching and research, but their approaches vary: those in Kocaeli, Mersin and Eskişehir rented physical venues, while “Off-Academy” in Berlin engineered a platform for online teaching. What they offer varies widely, which is part of their appeal: one can take a course on contemporary debates in Marxist theory in Kocaeli, or learn how to ride a bicycle in Mersin.

Most of them are quite active and engaged with their communities, offering workshops and lectures on an ongoing basis. They are determined to find a new democratic model of education and research, as well as of collective action and resistance.

Kocaeli Academy for Solidarity

The first solidarity academy was established in Kocaeli, a city that sits at Istanbul’s eastern border, by 19 signatories who were dismissed from Kocaeli University, all at once, by way of an emergency decree published on 1 September 2016.

They emptied their rooms in the university on 7 September, and were celebrating the opening of “Kocaeli Academy for Solidarity” only three weeks later, with a big and excited crowd including academics from all over the country and abroad. The first of their “Wednesday Seminars” series, free and open to everyone, was held less than a month after they left the university.

Almost two years later, KODA is bustling with activity: the Wednesday Seminars usually draw close to a hundred people. Some recent titles were “The secret subject of art: women”, “Introduction to critical law” and “Recent international developments and struggles for worker health and safety”.

In February, they rented a venue for the “School of Life”, which offers free, three-month long workshops, with titles such as “Discussions in Marxism”, “Democracy and Computer Games” and “20th Century Art”, and one where the participants made a music map of Kocaeli with musicologists.

They launched a collective research project on the urban history and transformation of a state owned paper factory from the republic era. In June, they held a four-day summer school titled “Authoritarian Times: Rights, Freedoms, and Turkey”, in memory of the signatory academic who committed suicide, Dr. Mehmet Fatih Traş.

Derya Keskin, one of the signatories dismissed from her position at Kocaeli University and banned from public service, is one of the founders and most active members of Kocaeli Academy for Solidarity. She worked as an Assistant Professor of Labor Sociology in the Department of Labor Economics and Industrial Relations at Kocaeli University for about five years.

During a phone interview, Keskin explained that many of the dismissed academics had strong bonds from the start. They had already experienced working together outside the university, in the Education and Science Workers Union (Eğitim-Sen) and another platform they had founded to discuss alternatives for the mainstream academic model. The academics dismissed from Kocaeli University started off the seminar series, gave a seminar each, then started inviting those who had been dismissed from other universities.

Keskin talked about the police presence during the seminars, saying the undercover police comes to sit in the cafes below or walk around their street. Some students have been afraid to come. “They see us on the street and hug us, saying they are sorry they can’t come. There are 70 thousand students in prisons” she said.

The hotel they wanted to rent a room in for their two day international conference in March, titled “Beyond University: Critical, Emancipatory and Solidarist Endeavors”, asked for a permission from the local police just a few days before the conference started. There was no legal need to, but the hotel demanded it despite the academics’ resistance, and they decided to change locations. The police still came both days and asked what they were doing, writing up a report. “We told the police they could come and have tea, that everything was open to the public anyways,” Keskin said.

Regarding the recent lifting of the state of emergency, “In practice, it doesn’t look like it’s ending because they already started the process of changing the laws to make the emergency rule permanent,” Keskin said, adding that all oppositional forces in the country should be alert and proactive in the battle for democracy.

Kültürhane: A cafe, library and cultural hub on the southern coast

The University of Mersin, located on Turkey’s southern Mediterranean coast, started firing signatory academics rapidly in January 2016, the same month the peace petition was made public. Over ten signatories – about half of them – left Turkey before they were banned from public service and their passports were cancelled, said Ulaş Bayraktar over a phone interview. Bayraktar is one of the signatory academics who worked as an associate professor at the Public Administration faculty of Mersin University. Eventually all 21 signatories, including Bayraktar, were removed and banned from public duty with an emergency decree published in April 2017.

Those who moved abroad left behind a mountain of books – thousands of them, mostly in social sciences – with their colleagues. Bayraktar, two other signatory academics, and an activist friend started to talk about what they could do with these books that were waiting in boxes. There wasn’t too much academic debate; they quickly agreed to rent a space and open a library. Their plans kept expanding to include a cafe and cultural venue, and to their surprise, they found and rented the perfect spot within 10 days.

The space was a collective effort; an architect friend designed it, funds were raised through an online crowdfunding campaign to cover most of the expenses, and “Kültürhane”, (“House of culture”) was opened in September 2017.

Open seven days a week, it has already become a buzzing cultural hub hosting all sorts of events, from academic panels to packed movie screenings, concerts by the Mersin chamber choir, bicycle courses for adults and sourdough bread making workshops. The library has over eight thousand books. Their affordable and spacious cafe, selling coffee from Zapatista cooperatives in Mexico, and tea from the Hopa Tea Cooperative in Turkey’s Black Sea region, also draws a crowd. They set up a food cooperative initiative that connects local producers with buyers – they have even purchased eggs from a banned signatory academic. Bayraktar admitted that their air conditioning is also a major draw for students in Mersin’s summer heat.

The police have shown interest in Kültürhane’s activities as well. Bayraktar mentioned that they know the local police have started investigating them. “They don’t need to work too hard, everything we do is on Youtube,” he said. Students have told them they were warned by the university to not go there, because they were under surveillance.

“Not everyone who comes here shares our political views,” said Bayraktar. “I call this being expelled from the public to the public. People from my city who I haven’t met once for 10 years in my academic career, I’ve met them here, some of them with similar views, some totally different. This is proof that hope is still alive here, not hatred or rage.”

In 1980, when Bayraktar was five years old, his father, a soldier within the Turkish army, was killed by the PKK, the Kurdish militant group considered a terrorist organization by Turkey. “I signed that petition so more families wouldn’t have to go through what we did,” he said.

Bayraktar said that they interpreted the Gezi Park protests as proof that their way of organizing was valid, focusing on sharing economies, setting up networks and spaces of commons, such as cooperatives, and basically organizing within daily life, not necessarily as part of a political party or union. “We are trying to find a new language”.

They plan to keep growing, with an ongoing crowdfunding campaign for various goals, such as being able to bring in academics from all over the country and world for talks.

The Off-University

In addition to an ongoing seminar series at the Germany Solidarity Academy, in Berlin, signatory academics founded “Off-University”, a free online teaching platform that went live in October 2017, at off-university.com.

Their first conference was titled “Tough Questions About Peace”, which consisted of 16 video lessons that dismissed academics from Turkey had recorded in their homes and uploaded to the website. They also created a confidential, encrypted platform where students could chat online with the professors anonymously, after listening to the online courses.

Urban historian Julia Strutz, a signatory who works as a researcher at LMU Munich University, is one of the founders of the initiative. Strutz was living in Turkey with her husband, also a signatory academic, until the coup attempt. Thinking they would have trouble renewing her residency permit, and concerned about their children, they decided to move to Berlin.

On a phone interview, Strutz explained that their association’s official name is “Organisation für den Frieden”, which they abbreviated as “Off” to convey the idea that this is not a typical university, and that it was founded by academics pushed outside the mainstream academy.

“The Turkish government is trying to silence academics, and this is our way of resisting that, through digital means,” Strutz said. The online platform was a solution for academics whose passports were cancelled, or those without the means to travel.

The group also held a second lecture series, with 11 courses on “Issues in Contemporary Turkey”, held live at Osnabruck University in Germany between April and July, which was uploaded online as well.

Getting Credit

One of Off-University’s major goals was to be able to offer actual university credits to students who take their classes, and they have taken one major step toward that. Strutz explained they arranged for a course to be offered at Potsdam University near Berlin, taught by an academic on staff at the university as well as by a signatory academic from Ankara, Turkey. The academic from Turkey will be paid by the university, and the students will be able to get real credits for the course. They plan to expand this model to other German universities and hope to arrange five such courses in the fall.

Off-University also set up a collaboration with Kiron Open Higher Education, a Berlin-based initiative that helps refugees access higher education through free online courses, so that the dismissed signatory academics can teach refugee students. “We started with academics from Turkey, but we want to spread this knowledge to all geographies longing for peace,” Strutz said.

Hope, strength, and dignity in the face of heavy consequences

On 8 July – three days after the Prime Minister announced the emergency rule would be ended – the most recent decree banning 18 more signatories from public service was published.

Then there are the criminal lawsuits, launched against over 350 academics, mostly from Istanbul universities. The indictments, according to the lawyers, have been “copy-paste texts”, accusing academics of “terror propaganda” because they signed the petition. So far 19 cases have been concluded, with academics given suspended jail sentences of 15 months.

“We think we might be next in line,” Keskin said, because the lawsuits against academics started in Istanbul, and Kocaeli sits on its border.

Despite the heavy consequences, and no finish line in sight, she refuses to give up hope and the work of the Kocaeli Solidarity Academy: “What we get in return is our dignity and our life, because we’re still academics and together with our students. That gives me the power to get up and go about my day.”

Summer school at Kocaeli Academy for Solidarityhttps://www.facebook.com/koudayanisma/photos/a.1060554100741204.1073741829.883111768485439/1061297117333569/?type=3&theater

Kocaeli Academy for Solidarity teachers and students (with completion certificates) https://www.facebook.com/koudayanisma/photos/a.892701684193114.1073741828.883111768485439/1062749483854999/?type=3&theater

“We told the police they could come and have tea, that everything was open to the public anyways”Derya Keskin

Kültürhane’s library has eight thousand donated books, mostly from dismissed academics https://www.instagram.com/p/BlBP3KCAXiS/?taken-by=kulturhane.mersin

A recent movie screening at Kültürhanehttps://www.instagram.com/p/BllMbPKF6Gm/

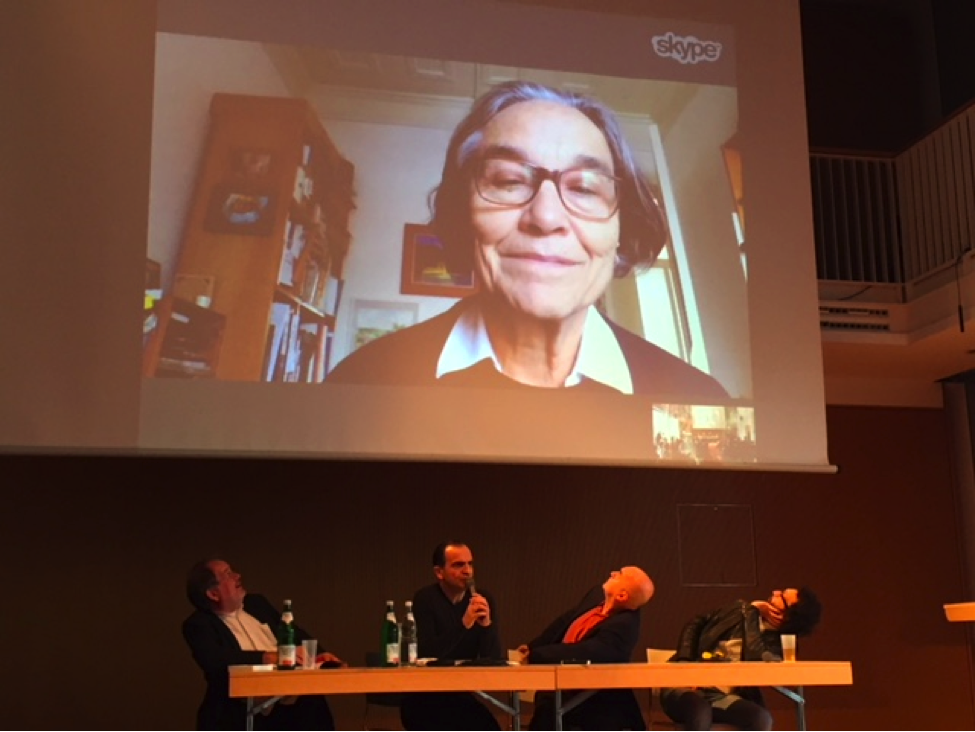

Off University’s “Tough Questions About Peace” conference opening in Berlin

“… This is proof that hope is still alive here, not hatred or rage.”Ulaş Bayraktar