July 2021 in Europe and Central Asia: A free expression round up produced by IFEX's Regional Editor Cathal Sheerin, based on IFEX member reports and news from the region.

July saw the public inquiry into Daphne Caruana Galizia’s death conclude that Malta bore responsibility. The month also saw the Belarusian authorities attempt to purge civil society; an increase in police violence directed at journalists in Turkey; revelations that Hungary’s government deployed illegal spyware against its critics; and an apparent contract killing of a journalist in the Netherlands. But there were very welcome developments regarding journalists’ safety in North Macedonia.

The tentacles of corruption

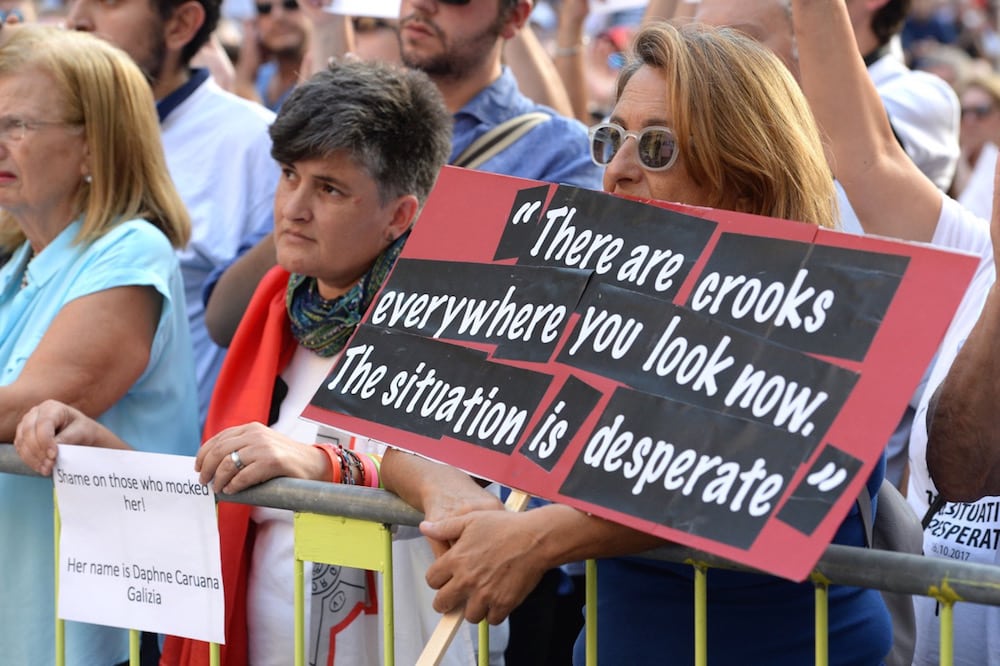

The State of Malta bears responsibility for the death of Daphne Caruana Galizia: that is the damning verdict of the public inquiry into the 2017 murder of the journalist.

Although the inquiry’s report, published on 29 July, does not find proof of the government’s direct involvement in the killing, it does find that former Prime Minister Muscat’s administration had created a “favourable climate” for the crime to be committed:

“It created an atmosphere of impunity, generated from the highest echelons of the administration inside Castille, the tentacles of which then spread to other institutions, such as the police and regulatory authorities, leading to a collapse in the rule of law”.

The report states that the board of inquiry believes that Caruana Galizia was murdered because she wrote about the close ties between big business and politics, and that “whoever planned and carried out the assassination did so in the knowledge they would be protected by those who had an interest in silencing the journalist”.

The report also makes a series of recommendations with regard to tackling corruption, protecting the right to information and journalists’ safety. You can read these in an English translation of the report, provided by the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation.

“A purge is underway”

July saw a huge ramping up of the persecution of independent voices in Belarus and, in President Lukashenka’s own words, a “purge” of civil society.

Dozens of NGOs are being targeted for liquidation (often for alleged registration errors), including IFEX member the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) and PEN Belarus. During a wave of raids mid-month, at least 60 offices and homes of rights defenders were searched, over 30 people were interrogated, and 13 were detained. The organisations targeted include those working with vulnerable groups, such as children, senior citizens and people with disabilities. In public, Lukashenka has described these NGOs and their workers as “gangsters” and “foreign agents”; he has suggested that as many as 2,000 of them are in his sights.

The attempted purge has provoked global outrage. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights called for an end to the harassment of civil society. IFEX members and 161 civil society organisations around the world called on the international community to hold the Belarusian authorities accountable for the attacks on NGOs. PEN America launched a letter-writing initiative (open to the public) to show solidarity with PEN Belarus.

One of the organisations raided by the authorities was Gender Perspectives, which works for gender equality and helps victims of domestic violence. Shortly after finding itself targeted, the organisation announced that it would be suspending its domestic violence hotline indefinitely.

Those who work in the arts are also under pressure. According to PEN Belarus’s recently published report, 621 culture sector workers had their human rights violated during the first half of 2021.

Early July saw the crackdown on Belarus’s embattled independent media intensify, with raids on offices and homes, and at least 30 arrests. By mid-July, there had been 63 raids and arrests targeting journalists and media outlets. Those targeted included Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, Nasha Niva and Belsat, which was officially declared extremist in late July (sharing or posting content from Belsat now carries a fine or jail time of up to 15 days).

Women have often been at the forefront of the resistance to the Lukashenka regime; according to BAJ, 16 of the 27 journalists currently detained and facing trial are women. This month, exiled opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya called for a day of solidarity with women in Belarus; in response, Justice for Journalists launched an appeal for letters of solidarity to be sent to women journalists jailed by the regime. For more on how women are trying to hold Lukashenka to account, take a look at the Coalition for Women in Journalism’s special report.

Tsikhanouskaya visited the US this month, where she attended the first Friends of Belarus congressional caucus group aimed at supporting the Belarusian democratic movement. She also spoke to PEN America about the current situation in her country and the future of the opposition movement: check out the podcast of the interview.

According to the Belarusian human rights organisation Viasna, there are currently 586 political prisoners in the country. One of them is the opposition presidential candidate Viktar Babaryka, who was sentenced to 14 years in prison this month on highly dubious corruption charges. The EU said that he had been jailed solely for exercising his political right to stand as a candidate in the 2020 presidential elections; it called for his immediate release and the release of all Belarus’s political prisoners.

Maxim Znak – Babaryka’s lawyer and a member of the pro-democracy Coordination Council of Belarus – will be tried behind closed doors in August with the detained opposition leader and fellow Coordination Council member Maria Kalesnikava. Both are charged with “conspiracy to seize state power in an unconstitutional manner” and “establishing and leading an extremist organization”.

At the end of the month, a group of organisations including ARTICLE 19 and Reporters Without Borders announced that they had filed a complaint to the United Nations’ Working group on arbitrary detention in the case of NEXTA editor Raman Pratasevich. Pratasevich has been detained (first in jail, now under house arrest) since May, when the Belarusian authorities forced his Ryanair flight to land in Minsk in order to arrest him.

Please check out IFEX’s regularly updated Belarusian chronology, where we bring together all our monthly summaries of IFEX members’ activities and other key developments in Belarus.

“Execution lists”

The crackdown on journalists and opposition voices in Turkey goes on. July saw numerous worrying developments.

Among them is the ongoing rise in cases of police assaulting journalists, exemplified by the wounding of over 20 reporters who were covering protests in Istanbul and İzmir on 20 July. A recent report by Expression Interrupted notes that this increase in violence corresponds to a circular issued in late April by the General Directorate of Security which bans audio and video recording during public demonstrations.

Women reporters are increasingly finding themselves the targets of police brutality: according to a report by the Coalition for Women in Journalism, violence against women journalists increased by 158% during the first half of 2021, with 44 women reporters saying they had been physically attacked by police officers.

Turkish journalists in the diaspora are at risk too. Alarmingly, the German government confirmed this month that a number of “execution lists” were in circulation, targeting exiled Turkish activists and journalists in Germany. The lists reportedly include such well known journalists as Can Dündar, Hayko Bağdat, Fehim Işık and Ahmet Nesin. The International Press Institute has called on the German authorities to investigate the circulation of the lists and ensure the safety of those named in them.

It’s not just violence (or the threat of it) that is used to deter Turkey’s independent journalists. The recently amended Press Card Regulation makes it almost impossible for dissenting journalists to obtain press cards (which are issued by the government). Expression Interrupted provides analysis of the situation, noting that half of the 44,000 applications for a press card made during the last three years were rejected. The Committee to Protect Journalists has called for press card reform.

In late July, IFEX members raised their concerns over proposals to introduce new regulation of “fake” and “foreign-funded” news following statements by President Erdoğan and other officials. According to reports, work will soon begin on a bill that could see social media users facing up to five years in prison for spreading disinformation.

Deaths follow attacks

July saw the deaths of two journalists following violent attacks.

Dutch organised crime investigator Peter R de Vries died in the Netherlands nine days after he was shot in an attack that bore all the hallmarks of a contract killing. The public prosecutor has linked de Vries’s death to his work.

In Georgia, journalist Alexander Lashakarava was found dead at his home days after he and approximately 50 other journalists were savagely beaten by a crowd of homophobic thugs at a Pride march in Tbilisi. The violence, which also targeted LGBTQI+ marchers, was encouraged by figures in the Georgian Orthodox Church. Police attending the event did little to prevent the attacks. LGBTQI+ people now report feeling unsafe in the street.

The “Victator”

There was further evidence this month of Hungary’s descent into bigoted authoritarianism.

Following EU demands that the government withdraw recent legislation banning the “promotion” or depiction of homosexuality or transgender people to under 18s, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán announced that he would instead hold a national referendum on the law by early 2022.

The EU is taking legal action against Hungary because of this recently adopted law. It is doing the same to Poland as a result of its discriminatory so-called “LGBT-free zones”.

It was revealed this month that Orbán’s government had deployed NSO spyware against investigative journalists, activists and at least one opposition politician, thereby gaining access to their phones’ messages, photos, emails, calls and microphones. Citizens took to the streets of Budapest to protest this illegal surveillance, calling Viktor Orbán the “Victator”. The Budapest Regional Investigation Prosecutor’s Office said that it was opening an investigation into the use of the spyware, though there is scepticism that these efforts will amount to much. Orbán’s government seems unwilling to engage with the issue in a substantive way: opposition MPs called for an emergency meeting of the parliament’s national security committee, but the MPs from the ruling party didn’t turn up.

In brief

There was extremely welcome news from North Macedonia in July, when the Justice Minister announced amendments to the Criminal Code which will strengthen journalists’ safety. The proposed changes include new penalties for assaulting press workers and the criminalisation of online harassment; attacks on journalists will be treated in the same way as assaults on police officers.

The UK Government has proposed changes to the Official Secrets Act which could see journalists labelled as spies and jailed for up to 14 years for doing their jobs.

The European Commission published its 2021 Rule of law report and IFEX members were underwhelmed. Human Rights Watch criticised the report for lacking a clear strategic vision of how to tackle the erosion of rule of law in certain states, such as Poland and Hungary. The members of the Media Freedom Rapid Response mechanism had similar concerns, saying that “depoliticised analyses” had resulted in a report that did not adequately convey the depth of the crisis in Poland and Hungary.