August in Middle East and North Africa: A free expression roundup produced by IFEX's Regional Editor Naseem Tarawnah, based on IFEX member reports and news from the region.

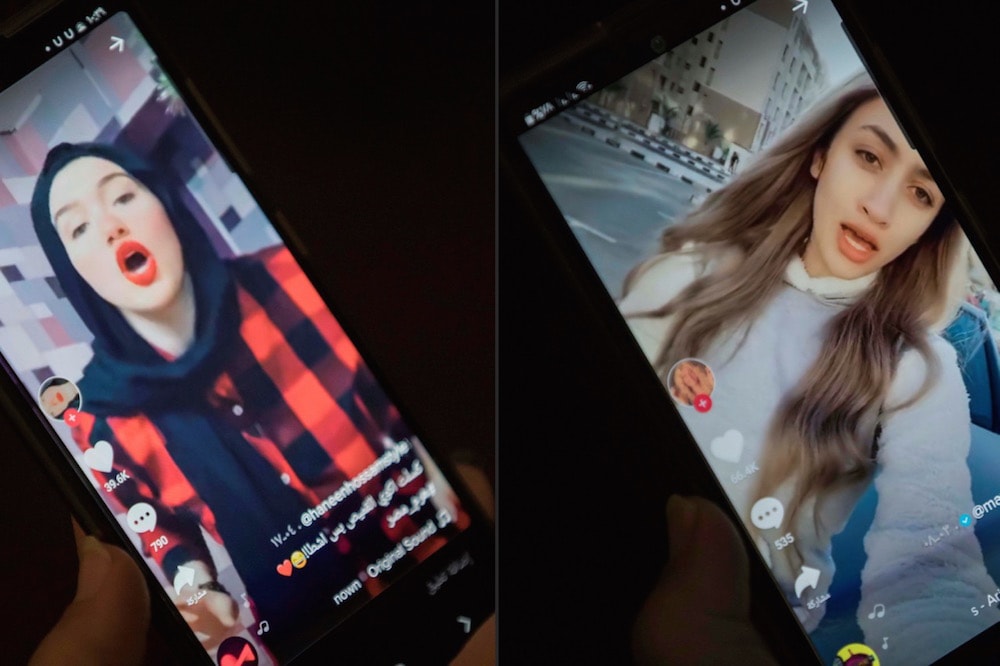

Egypt’s TikTok girls and social media users take aim at rape culture

The persecution of young female TikTok users in Egypt continued in recent weeks. According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), popular content maker Manar Samy received a three year sentence and a fine for “inciting debauchery, immorality and stirring up instincts” through her online dance videos. And in July, prominent Tiktokker Mawada was sentenced to two years in prison for violating family values, while social media influencer Hadeer al-Hady, was arrested in the same month for posting “indecent” videos and remains in pretrial detention. According to the rights group, recent media reports suggest al-Hady may be subjected to a virginity test.

Five of the women arrested will have their appeals heard this month, and 17-year old Aya, who was arrested in May for “morality offences” after posting a video where she accused several men of raping, filming and blackmailing her, has reportedly been in a government-run women’s shelter while the investigation into her assault is ongoing.

In the face of this ongoing repression of their online free expression, women in Egypt have continued to leverage social media platforms to shame alleged attackers and decry a culture of rape and sexual assault where perpetrators have typically gone unpunished.

Earlier this year an online video showing a mob descending upon a screaming woman sparked public outrage and the arrest of at least seven people. Over the summer, dozens of women accused college student Ahmed Zaki of rape on an Instagram account resulting in his arrest.

The account called “assaultpolice” also gathered testimonies related to the alleged gang-rape of an underage woman by six wealthy men, forcing an investigation. However, activists say the case has resulted in a widening crackdown on feminists and the LGBTQI+ community. In early September, security forces arrested six witnesses who provided testimony in the investigation and threatened them with charges of “violating Egyptian family values”and “debauchery”.

A campaign of “intimidation and vengeance”

Prominent human rights defender and director of IFEX member Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS), Bahey elDin Hassan, was given a 15-year prison sentence over a tweet in which he criticized the judiciary. Hassan, a founder of Egypt’s human rights movement, was prosecuted under the penal code and a new draconian cybercrimes law that critics say is a severe obstacle to freedom of expression.

According to CIHRS, the sentence comes in the context of a wider ongoing state security campaign of “intimidation and vengeance” that has targeted Egyptian rights defenders “both inside and outside the country, with the goal of deterring them from exposing serious human rights crimes.”

In what is reportedly the longest sentence ever imposed on a human rights defender in the country, the verdict was met with widespread condemnation by activists, social media users, and rights groups including the IFEX network.

“Bahey is a deeply respected colleague with a decades-long history of promoting and defending freedom of expression,” said IFEX Executive Director Annie Game in a statement calling for the unjust sentence to be quashed, adding: “His only ‘crime’ is his lifetime of work standing up for the basic human rights of Egypt’s people, and his sentence is a stark reminder that Egyptians deserve so much better than a politicised judiciary in the service of authoritarianism.”

Iran: Internet shutdowns and other indecent acts

Last month, authorities shut down the Tehran-based economic daily Jahane Sanat over its reporting of the country’s COVID-19 figures. “This latest move to target a newspaper for reporting on COVID-19 is an irresponsible act in the face of the biggest public health crisis of our time,” said CPJ MENA representative Ignacio Miguel Delgado. “The closure of Jahane Sanat is an unfortunate continuation of Iran’s long practice of suppressing information to the detriment of the Iranian people’s well-being,” he added in a statement.

Iran is currently battling a second wave of cases, and a recent data leak revealing attempts by authorities to cover-up figures has underscored concerns over the health situation in Iran’s overcrowded prisons. With many women human rights defenders, prisoners of conscience, and journalists at risk, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) called on the UN special rapporteur on human rights in Iran to inspect the country’s prisons in light of the revelations.

Yet, despite the rising health risks of overcrowded prisons, authorities have been undeterred in their pursuit to jail citizens for exercising their freedom of expression. This includes artists who have been recently targeted for acts deemed “indecent” or “immoral” under the penal code.

Musician Mehdi Rajabian was arrested last month and is now facing trial for working with female singers and dancers, while earlier this year, female singer Nezzar Moazzam was summoned to court for singing for a group of tourists while wearing a traditional costume. Composer Ali Ghamsari was also banned from performing “until further notice” after refusing to remove a female singer from his line-up during a concert in Tehran.

“You can imprison my body, but never my conscience!

For signing a statement objecting to the targeted killing of protesters during nationwide protests in November 2019, Iranian lawyer, poet and activist Sedigheh Vasmaghi was sentenced to six years in prison by the Revolutionary Court on charges of “propaganda against the regime”. Earlier last month, Vasmaghi refused to attend a hearing at the court in protest of the unfair judicial process, providing a statement of defence in her absence.

In response to the verdict, the prolific writer protested the sentencing, court, and the government which she says has abused the judicial system to suppress peaceful protest. “You can imprison my body, but never my conscience! I prefer prison to shameful silence in the face of injustice and corruption,” wrote Vasmaghi in a published statement.

According to a new Amnesty International report, authorities subjected hundreds of protesters following the November 2019 protests to arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, torture and other ill-treatment. Widespread torture was routinely used to produce forced confessions for their sentencing in what the organization says were “grossly unfair trials”.

Concerns are also rising over the future of Internet access in Iran as the government works to promote the development of a national network. Rights groups have noted the regime’s track record of disrupting Internet communications during protests in violation of human rights. This includes recent network disruptions during an online protest against executions in July, as well as an Internet shut down in the city of Behbahan during an anti-government protest. According to ARTICLE 19, the national network has diminished costs of shutdowns for the country, allowing authorities to cut off access to the global Internet without disrupting crucial national services.

Lebanon: Protesters targeted in weeks after port blast

The shockwaves of last month’s port explosion in Beirut, which claimed 190 victims and left hundreds of thousands homeless, have reverberated deeply throughout the country’s anti-government protest movement, igniting an already fragile state of affairs. In the past months, Lebanon has reckoned with the COVID-19 pandemic, electricity shortages, a shattered trust in government, an army whose power has been left unchecked in a state of emergency, and an economy on the verge of collapse. The port blast, revealed to be a result of government mismanagement, has left protesters seething on the streets, renewing their demands for change and accountability.

Sadly, their calls fell on deaf ears after security forces used lethal force against tens of thousands of protesters during an 8 August protest in Beirut. Hundreds were injured by security forces who used live ammunition, rubber bullets, and tear gas on crowds. At least 14 journalists were also injured while covering the protests.

Rights groups, including IFEX members RSF and The Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR), denounced the systemic targeting of journalists and protesters, with GCHR calling the disproportionate use of force against them “a glaring example of the dangers to civil society when invoking emergency powers.”

Moderating Arabic hate speech against LGBTQI+ community

Pressure has been mounting on Facebook to be more reactive to online threats facing the LGBTQI+ community in Egypt and the MENA region. Activists say the social media company’s moderators are ill-equipped to identify Arabic hate speech and that community rules are poorly enforced. In the wake of Egyptian LGBTQI+ activist Sarah Hegazy’s recent death, rights groups have increased calls for better moderation.

However, enforcing policies can be a complicated terrain to navigate when it comes to languages. According to Jillian York, director of international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, “(Social media companies) are really bad at defining and dealing with incitement and dehumanizing language,” adding that Facebook “have a dearth of content moderators in a number of languages where they should have a lot more”.

In Brief

In Jordan:

Rights groups say Jordanian authorities have been exploiting the COVID-19 emergency laws to crack down on freedom of expression and assembly following nationwide protests last month. The protests were in response to the arbitrary closure of the country’s Teachers’ Syndicate, the country’s largest independent trade union, and the arrest of its board members in July.

According to HRW, Jordanian authorities forcibly dispersed protests, attacking and arresting numerous teachers, protesters and journalists. A media gag order banning coverage was also issued, leading to several arrests. While some of those arrested have since been released, many remain in detention.

In another worrying sign of the growing degradation of the country’s press freedoms, acclaimed cartoonist Emad Hajjaj was briefly arrested hours after publishing a satirical cartoon criticizing the UAE-Israel peace deal. “The arrest of Emad Hajjaj in a publishing-related case constitutes a flagrant violation of freedom of expression and a sort of intimidation practiced by the Jordanian government against a creative artist who is respected and appreciated by millions of people,” said Arab Network for Human Rights Information director Gamal Eid, in a statement condemning Hajjaj’s arrest.

In Algeria:

Journalist and editor of the Casbah Tribune news site, Khaled Drareni was handed a shocking three-year sentence after being charged with “inciting an unarmed gathering” and “endangering national unity” for his coverage of Algeria’s “Hirak” protest movement. Rights groups denounced the verdict and called for his immediate release.

The sentencing comes amid rising concerns over the new government’s attitude towards the press. Recent weeks saw former radio reporter Abdelkrim Zeghileche sentenced to two years in prison for insulting President Abdelmadjid Tebboune on Facebook, as well as the detainment of France 24 journalist Moncef Aït Kaci and his cameraman Ramdane Rahmouni on charges of working without accreditation for a foreign TV channel and receiving illegal funding.

Oral History of Covid-19 in MENA

As part of an ongoing effort to chronicle the distinct experiences of people and organizations during the COVID-19 pandemic, IFEX members from the MENA region have been sharing their stories of how life has changed throughout the global health crisis.

Organizations including, Social Media Exchange (SMEX), Visualizing Impact (VI), Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB), and the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR), and the Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media (7amleh), spoke about the demands of balancing home and work life with shifting realities, as well as the psychological toll of lockdowns.

At SMEX, operations manager Lucie Doumanian said working from Lebanon allowed the organization to build resiliency ahead of the pandemic. “In Lebanon, we lived the revolution from October 2019 to this day and alongside came the COVID19 pandemic. We, as an organization, feel we’ve faced some really hard challenges, which has made us somehow more resilient to anything that might come our way. However, there is a clear need for further support and cooperation among civil society in itself, and IFEX’s network as well.”

Meanwhile, for Jessica Anderson, co-founder and operations manager of VI, the pandemic became another factor their organization has had to deal with alongside competing issues.

“The sense of being in perpetual, reactive “emergency mode” is tiring,” wrote Anderson. “In addition to the pandemic, this year VI and its partners have been impacted by other major events. From the Israeli annexation plan and Black Lives Matter uprisings, to the crisis in Lebanon. In such times, should an organization like ours shift the focus of our work or stay the course? We’ve done a bit of both. Also, when people’s attention is so focused on one topic, how do you talk about other important events and issues? These are just some of the challenges we’ve faced and thought about this year.”

IFEX will be sharing its members’ voices in the coming weeks.